March 9, 2021

Meet the Makers Behind the Tufted Rug Renaissance

Tufting is blowing up, and no it’s not just a TikTok trend. Metropolis spoke with the artists and designers who are helping popularize the technique and some who have taken it up during quarantine.

Just like perfect loaves of sourdough, some may have noticed an influx of handmade rugs on social media feeds this past year. As a way of channeling restless quarantine energy into learning new skills, artists and designers around the globe have been leaning into the emotional—and political—role of craft. And for many, embracing and sharing the process is as valuable as the results. That’s where tufting comes in.

While some credit the inundation of shaggy, graphic rugs to the popularity of the oddly satisfying TikTok videos that document their creation, rug tufting is by no means a new process—after all, humans have been making rugs since the fourth century B.C. While colorful yarn being shot into fabric at high speeds is certainly captivating to watch, the reason behind the resurgence is more about access than aesthetics. Only recently could consumers to get ahold of a common carpet-industry tool: the handheld electric tufting machine (otherwise known as the tufting gun). For that, you can thank Philadelphia-based artist and educator Tim Eads.

A professional screen printer for 25 years before arriving at tufting, Eads stumbled upon the technique while operating a hand-printed handbag business. When one of his assistants introduced it to him, he says, “I was immediately drawn to it, found [the machine] online, and bought it.” He posted an image on his business’s Instagram and was met with tons of questions from followers wanting to know how to do it and where to buy the equipment. After that, he says, “It quickly took over my life.”

Eads was one of the first to bridge the gap between manufacturing and consumer. In 2018, he found a supplier for the machine and soon opened up his own store, which is now a leading supplier of tufting tools and materials. He and his ten-person team have pre-orders backed up for a while, partially because of a “global shortage due to COVID-19” and undeniably the popularity on TikTok has a little to do with it. Last November, they sold more than twice the number of machines as in all of 2019. “It’s insane,” he says, “January 2021 we were at 600 percent more sales than we did in January 2020 in just that one month.” The machines aren’t exactly cheap, averaging at about $300–$800, and that doesn’t include frames, yarn, fabric, or the adhesive needed to complete a piece.

But why now, when machine tufting has been in existence since at least since the 1930s? Eads points to a relatively small learning curve: Compared to other craft-based practices, the results are almost instantaneous. “For somebody who has never touched the machine, with the right tools and materials, they could pick it up and have a 24-by-24-inch tufted piece by the end of a six-hour workshop.”

Eads acknowledges that, of course, he didn’t invent the process or the machine. He points to contemporaries who have been working in the medium since before his website launched. One such person is Savannah, Georgia-based artist and designer Trish Andersen, who coincidentally is from Dalton, Georgia, where the first mechanized tufting machine was invented. Colloquially known as “The Carpet Capitol of The World” Dalton is home to over 150 carpet plants and a number of American flooring manufacturers including Shaw Industries, Mohawk, and Dixie Group.

A Savannah College of Art and Design fibers alum, Andersen explains that when she first started there was no information out there. Her first gun came in a box with zero instructions, and YouTube tutorials were few and far between. “Tim starting that website changed the game,” she says.

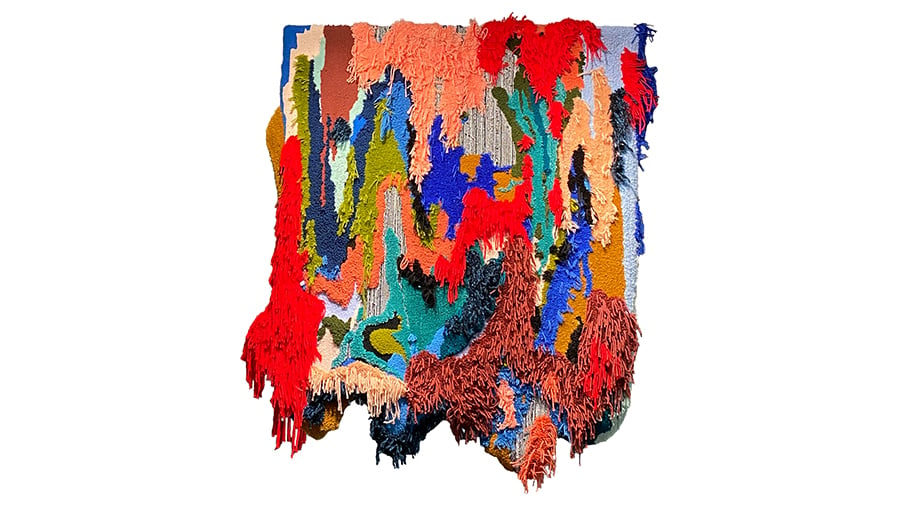

While the handheld tufting machine originated in the rug industry, many makers today use it to create works for the wall as opposed to the floor. When Andersen made a runner for her home that appears as if paint is dripping down a staircase, the image went “completely viral” and soon her inbox was filled with quote requests for rugs. “Me and my fiancé were just fixing up our apartment and I just made that for the hell of it. I don’t even make rugs,” she said laughing. Instead, her large-scale expressionistic wall pieces are sought after for residential and commercial spaces alike for their painterly quality.

She says that compared to other textile processes like weaving or knitting, “Tufting, for me, is much more like painting and drawing. You’re able to jump around the canvas, play with your colors, and move around your piece as a whole rather than line by line.” That energy is apparent in her 2019 installations for Design Miami which include high-pile textured wall hangings and a mirror that resemble swirls of mixed paint.

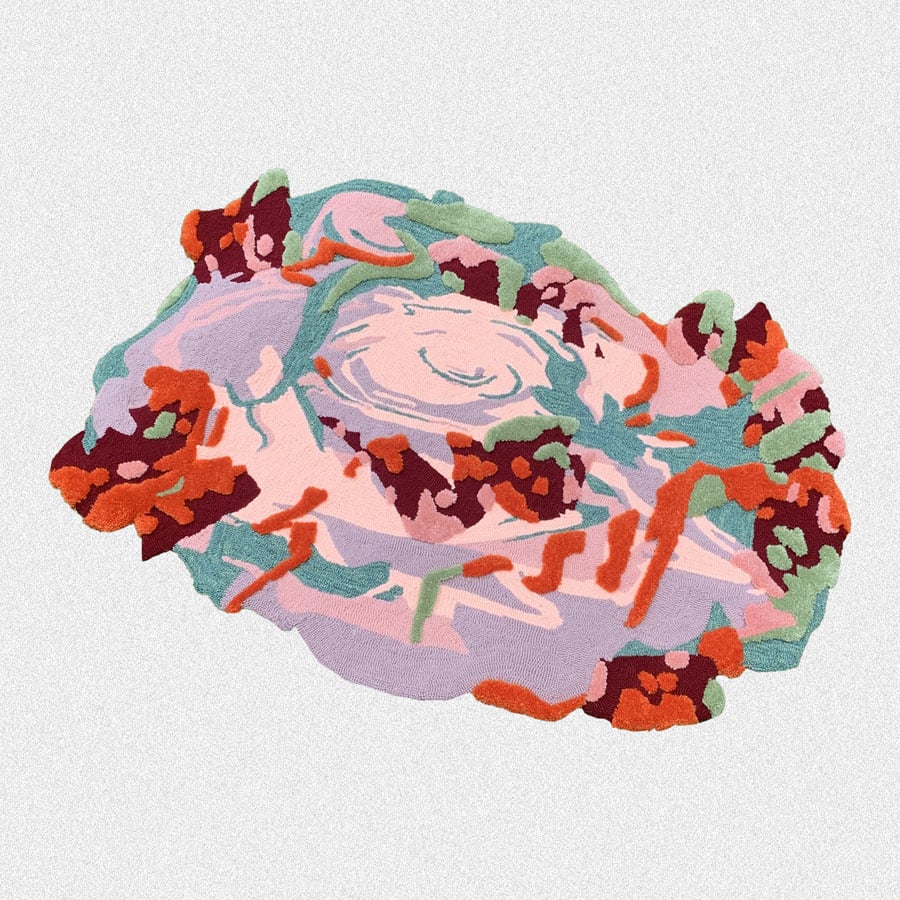

Artist Caroline Kaufman also views her practice as a marriage between fibers and painting. No stranger to commercial commissions, the Pratt Institute fashion design grad started tufting in 2018 and has since completed work for companies from Google to WeWork and Brooklyn’s new Ace Hotel where 25 of her asymmetric pieces adorn the walls of guest suites.

But like any other design technique or aesthetic gone viral, issues such as theft and copyright infringement are seemingly inevitable as individuals and large corporations alike walk the fine line between inspiration and imitation. Eads has found that people are using the tufting machine to recreate anything and everything in yarn, from logos to cartoon characters and he sometimes has to remind them that they “shouldn’t be touching copyrighted stuff.”

“As far as people taking your ideas or reproducing your exact work, I think it happens in art across all mediums, but social media definitely amplifies it,” Kaufman adds. “Sometimes I feel very vulnerable sharing things before they’re done because I have seen [copies] of my work pop up in places the next day.” Imitation comes with the territory and ultimately the positives outweigh the negatives she says, “In fiber, there is an abundance mentality. There kind of has to be because the practices predate us all.”

In fact, when it comes to craft wisdom and trade secrets, tufters are largely open and willing to share what they have learned and are working on. Andersen says, “I’m very big on community over competition and I think it’s been cool to see this community happen so quickly just around a tool.”

With the growing demand, Eads has even formed an online forum called Tuft the World for professionals and newcomers alike to meet, chat, trade insight, and share their work. With about 3,500 existing members, he says that lately, the community has been averaging about 100 new members a day.

For many, tufting has been a respite from COVID-related anxiety, endless news cycles, and rising screen time. Some use it as a means to resist the attention economy, others view its meditative qualities as a form of self-care. And while the process may easily garner likes and viewers, it’s not something that can be done while multitasking. In other words, says Andersen, “You can’t hold your phone and do it.” Perhaps this is why so many people are looking to try rug-making out for themselves despite the high costs for something many would consider a “hobby.” Andersen concludes, “You have to be really zeroed in to make it work. There is something really powerful about that.”

You may also enjoy “8 Sustainable Yarns and Fibers”

Would you like to comment on this article? Send your thoughts to: [email protected]

Register here for Metropolis’s Think Tank Thursdays and hear what leading firms across North America are thinking and working on today.

Recent Products

Products

How to Specify Stone Sustainably