March 26, 2025

Alberto Kritzler is at the Forefront of Regenerative Design in Mexico

Jaxson Stone: Can you tell me a bit about your research as a Loeb Fellow and what inspired it?

Alberto Kritzler: Growing up in Mexico City I experienced a city always on the edge of collapse where everyone experienced a common disaster: an aggressive urbanization process of mindless overdevelopment. My experience led me to believe that the way we currently live is unsustainable.

From this perspective, I sought to reframe business models that are usually based on exploiting land and people. My work aims the opposite, to reverse the destructive power of mindless overdevelopment by creating business models built across scales in urban and rural Mexico.

My research focused on the intersection of urbanization processes and sustainable design at a territorial scale from a systems approach (as opposed to sustainable buildings). That is where water and its infrastructure come into play.

Why is water such an urgent concern now, especially in Mexico?

Mexico’s constitution enshrines the right to water, yet Mexico is the number one bottled-water per capita consumer in the world. Our capital with 22 million people was built on a lake by draining it, yet we built a system to bring water from 138 miles away and over 2,000 vertical feet below (loosing around 40 percent along the way). In 2024 nearly 76 percent of the country was experiencing drought. In addition to this, the distribution of water is deeply inequitable. According to a study conducted by the Universidad Iberoamericana (January 2024) based on statistics obtained from National Institute of Statistics and Geography (INEGI), a little over 77 percent of the population in Mexico City does not have access to a sufficient amount of potable water to maintain a healthy life in accordance with WHO standards. An urgent question is: how do we adapt our cities and infrastructure to sustain life under these extreme conditions?

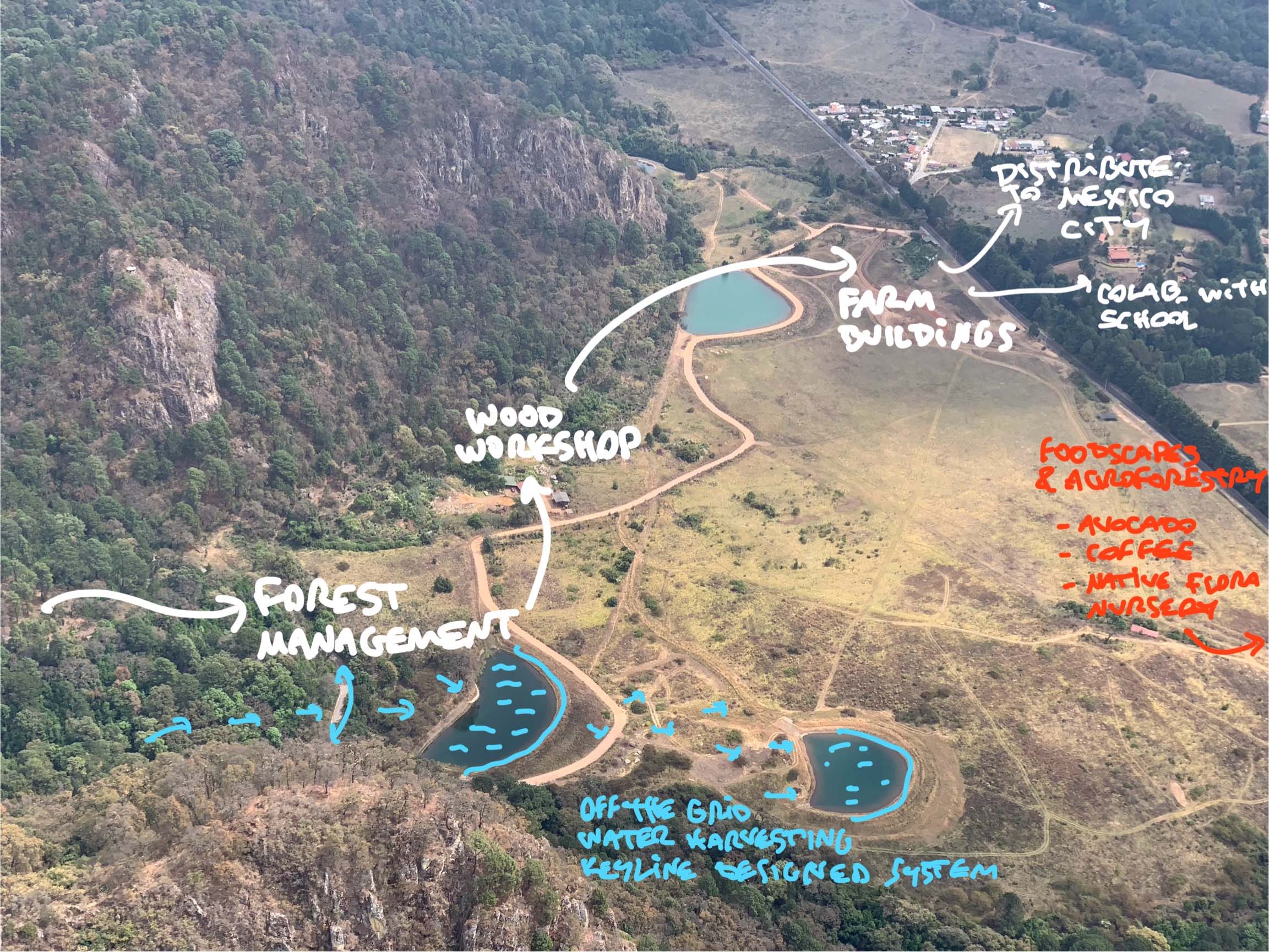

This is why one of the most crucial aspects of the Reserva Peñitas project is the design of the community’s water harvesting system, which serves as the foundation for everything else to function and adapt around it.

In your work, how do you define regenerative design, and what principles/practices do you apply to address water management and the needs of local communities?

Regenerative design goes beyond sustainability to design systems that proactively regenerate natural-based systems.

In terms of water: my work explores interconnected systems of water harvesting to increase self-sufficiency. In Reserva Peñitas I relied on permaculture principles and key-line design to create a water-autonomous community of almost 100 homes. The system relies on both the rooftops (at a small scale) and the basins (medium scale) to collect rainwater—the former provides water during the rainy season, the latter during the dry months. It is not always possible to achieve autonomy. However, in Mexico City, I have adapted over a dozen buildings (some over 100 years old) to harvest rainwater to increase their autonomy (an example: La Laguna, in Col. Doctores CDMX, an adapted factory from 1930s.

All of this, to have its potential impact, must belong to a larger scale design of living systems. An example of this: for La Reserva, I created the regions first native flora nursery so we could design a landscape that requires no irrigation, less maintenance and provides food for the local fauna. I’m working on replicating these same principles in the southern state of Oaxaca, Mexico with a community land trust on the pacific coast.

These methodologies are part of the course I will be teaching at the Landscape Department at Harvard Graduate School of Design in the Spring of 2025.

Alberto Kritzler recently opened Polistudio, an interdisciplinary office dedicated to environmental design through research, conceptualization, and the development of sustainable territorial models.

Would you like to comment on this article? Send your thoughts to: [email protected]

Latest

Viewpoints

Sustainability News Updates for Q2 2025

Renewable energy growth, carbon benchmarking, and circular design strategies shaping the built environment.

Viewpoints

Meet the Changemakers Shaping Tomorrow’s Buildings

METROPOLIS’s 2025 Spring Issue spotlights designers and architects going the extra mile, redefining what it means to design for climate, community, and lasting impact.