January 15, 2016

Alejandro Aravena Awarded Pritzker Prize

With this year’s selection, 2016 will be remembered as the year the Pritzker rallied around a vision of architecture as a social, ameliorative practice.

Alejandro Aravena, the 2016 Pritzker Prize winner

Courtesy Cristobal Palma

With this year’s Pritzker Prize awarded to Chilean architect Alejandro Aravena, 2016 will be remembered as the year architecture’s most eminent institutions rallied around a vision of architecture as a social, ameliorative practice.

Aravena, 48, has centered his practice around a string of clever social-housing projects set in developing-world nations. He’s bringing that expertise to the 2016 Venice Architecture Biennale, which he’s directing, under the first-person-activist theme, “Reporting from the Front.” Likewise, the first-ever Chicago Architecture Biennial, which wrapped up earlier this month, took a similarly humanitarian view of architecture, highlighting housing projects that, like Aravena’s, derive their value and power from the ingenious application of minuscule prices per-square-foot.

In 2001, Aravena founded ELEMENTAL, an architectural office-cum-“do tank” concerned with solving social problems through design. He served on the Pritzker selection jury from 2009 till 2015 and played a part, as some critics have noted, in pushing the award program toward more socially progressive laureates, such as Shigeru Ban in 2014. With ELEMENTAL, Aravena has designed a range of commercial and educational buildings (including several for the Catholic University of Chile, the architect’s alma mater), but low-income housing projects have formed the core of his work throughout.

The housing projects respond to a global crisis (the crush of rural migrants flooding into informal urban settlements) with local sensitivity. In his 2004 Quinta Monroy houses, Aravena found himself confronted with an impossible mandate: to design housing for 100 families at a paltry rate of $7,500 per unit, on relatively expensive land near Iquique, Chile. It was just enough money, he reasoned, to build “half a good house”—that is, a simple reinforced concrete two-story volume, one-half fitted out, the other, empty, capable of being converted to living spaces by residents.

Quinta Monroy Housing, 2004, Iquique, Chile (with residents’ additions)

Courtesy Cristobal Palma

In Chile and in developing countries around the world, informal settlements and houses are a matter of fact, and little can be done to prevent them. Why not, Aravena asks, prepare the site and make their installation as easy as possible? “You provide the frame, and from then on families take over,” Aravena said at a 2014 TED talk. “Slums and favelas may not be the problems. They may be the only possible solution.” This housing template, repeated elsewhere in Chile and in Mexico to the tune of 2,500 units, trusts residents to provide color, texture, and a sense of aesthetic variation—what we might call “architecture.” Instead, the design concerns itself with the housing infrastructure (utilities, foundations), which residents cannot easily install on their own.

This type of resourceful problem-solving, more than any technocratic sense of “innovation,” is a hallmark of Aravena’s work. His Catholic University Architecture School building, for example, saved money by borrowing a building-skin technique (zinc panels injected with Styrofoam) from Chile’s fruit packaging industry.

Aravena’s do-gooder architecture credentials are beyond reproach, but he’s hardly polemical, let alone moralizing, about the approach he’s taken. His affordable-housing projects sport flat roofs and pitched roofs alike, and they aren’t at all fussy or discriminating about which historical traditions they draw from. It’s an architecture that is plainly stated, taking whatever form it needs to for the benefit of those that need it most. “We are not concentrating on the handwriting,” Aravena told Alex Bozikovic of the The Globe and Mail, describing his design ethos. “We concentrate on what we are saying with our writing.”

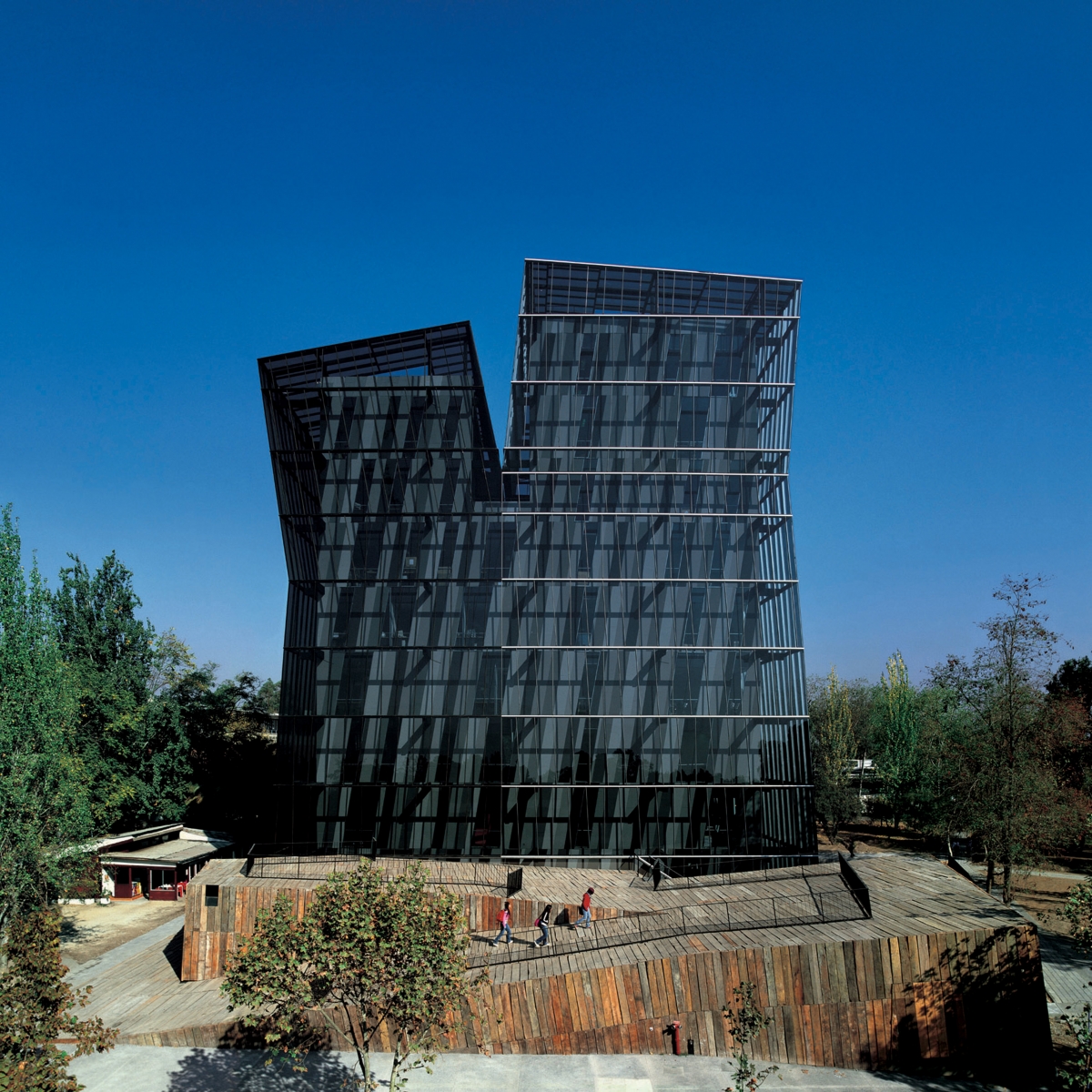

But Aravena isn’t beyond beauty for its own sake. His Bicentennial Children’s Park in Santiago is a scruffy but well-ordered set of hillside terraces connected by slides, fountains, and playgrounds that skirt the boundaries of landscape art. Many of his academic projects, like the UC Innovation Center at Catholic University, have an austere, monumental presence on the exterior, offset by light-filled atrium cores inside. This nod to Brutalism, arrived at more out of a Protestant vow of material economy than any high-style call-to-arms, puts Aravena on another of architecture’s cresting waves: the late Modernist revival of beton brut.

UC Innovation Center–Anacleto Angelini, 2014, San Joaquín Campus, Universidad Católica de Chile, Santiago, Chile

Courtesy Nina Vidic

The best buildings draw their power from architecture’s status as the sole omnipresent art form. Because it requires tremendous amounts of capital, energy, and effort to create, architecture can only begin far upstream in the culture, and so dutifully reflects its every permutation and facet. Aravena is insistent that architecture attuned to pressing issues needs to set down roots in these same broad social and economic kitchen-table concerns. Where can I build a house? How will I get to work? Will there be clean water? “One of the biggest mistakes that architects make is that they tend to deal with problems that only interest other architects,” he told the Guardian. “The biggest challenge is to engage with the important non-architectural issues—poverty, pollution, congestion, segregation—and apply our specific knowledge.”

And if architecture begins in the wider world, Aravena is not opposed to keeping his practice worldly, and that includes making money. He sees high-end design work as a way to strengthen his design muscles for when he has to scrimp and save as much as the residents of his affordable housing units. (He’s currently working on an office building in Shanghai for Novartis.) His firm is co-owned by Chilean energy giant COPEC. (It made $856 million in profits in 2014). “Everything we do is for profit. Even the social housing we do is for profit,” he told The Dallas Morning News. “Social housing required professional quality rather than professional charity.”

It’s one thing for a designer like Aravena to be at peace with the capitalist drive for profit, working within the system to find nooks and crannies in which to build good and honest dwellings for disenfranchised people. It’s another thing entirely to get the market to actively champion and reproduce these initiatives. No one has really cracked this code yet, but Aravena has already come closer than most. What happened when ELEMENTAL legitimized the shanty towns of Iquique with its Quinta Monroy development? After one year, property values tripled.

Monterrey Housing, 2010, Monterrey, Mexico (with residents’ additions)

Courtesy ELEMENTAL

Villa Verde Housing, 2013, Constitución, Chile (with residents’ additions)

Courtesy ELEMENTAL

Villa Verde Housing, 2013, Constitución, Chile (with residents’ additions)

Courtesy ELEMENTAL

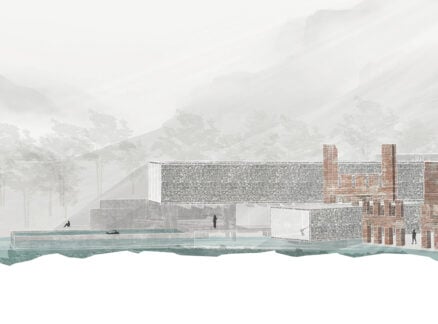

Mathematics School, 1999, Universidad Católica de Chile, Santiago, Chile

Courtesy Tadeuz Jalocha

Medical School, 2004, Universidad Católica de Chile, Santiago, Chile

Courtesy Roland Halbe

Siamese Towers, 2005, San Joaquín Campus, Universidad Católica de Chile, Santiago, Chile, University classrooms and offices

Courtesy Cristobal Palma

St. Edward’s University Dorms, 2008, Austin, Texas

Courtesy Cristobal Palma

Bicentennial Children’s Park, 2012, Santiago, Chile

Courtesy Cristobal Palma

Zach Mortice is a Chicago-based architectural journalist. Follow him on Twitter and Instagram, and listen to his architecture and design podcast A Lot You Got to Holler.