October 29, 2021

Brian Peters’ 3D Printed Ceramics Merge Art and Technology

“I design everything in a computer, but at the same time it has to be beautiful or have some kind of artistic expression.”

Brian Peters

“I would say what I’m doing now is kind of a mix of art and technology,” Peters explains, “I design everything in a computer, but at the same time it has to be beautiful or have some kind of artistic expression.” While Peters’s passion lies at the intersection of art, architecture, and fabrication, perfect machine-made objects aren’t the end goal, rather, process and discovery—from “hacking” existing printers to experimenting with nature-derived geometries—inform every step of his practice.

While most bricks, blocks, and tiles revolve around an extruded repeatable design, Peters explains, “3D printing can allow you to basically change from tile to tile, or from brick to brick. Each one can be slightly different.” By reinventing standard units of construction that have been around for thousands of years, he opens up a myriad of design possibilities that “could be a puzzle of 200 unique pieces.”

Take for example a lobby screen developed for the Eighth and Penn development in downtown Pittsburgh in 2019. The installation is made of 150 12-by-9-inch 3D printed earthenware blocks, each featuring three different designs. The block patterns are inspired by the historic building’s exterior ornamentation, and while digitally modeled and fabricated, they feature a unique woven texture that is achieved by Peters’s hand finishing, glazing, and firing processes. “The material has a mind of its own. So unlike other materials, like plastic or concrete, a lot can happen during the post-processing of it after it’s printed.”

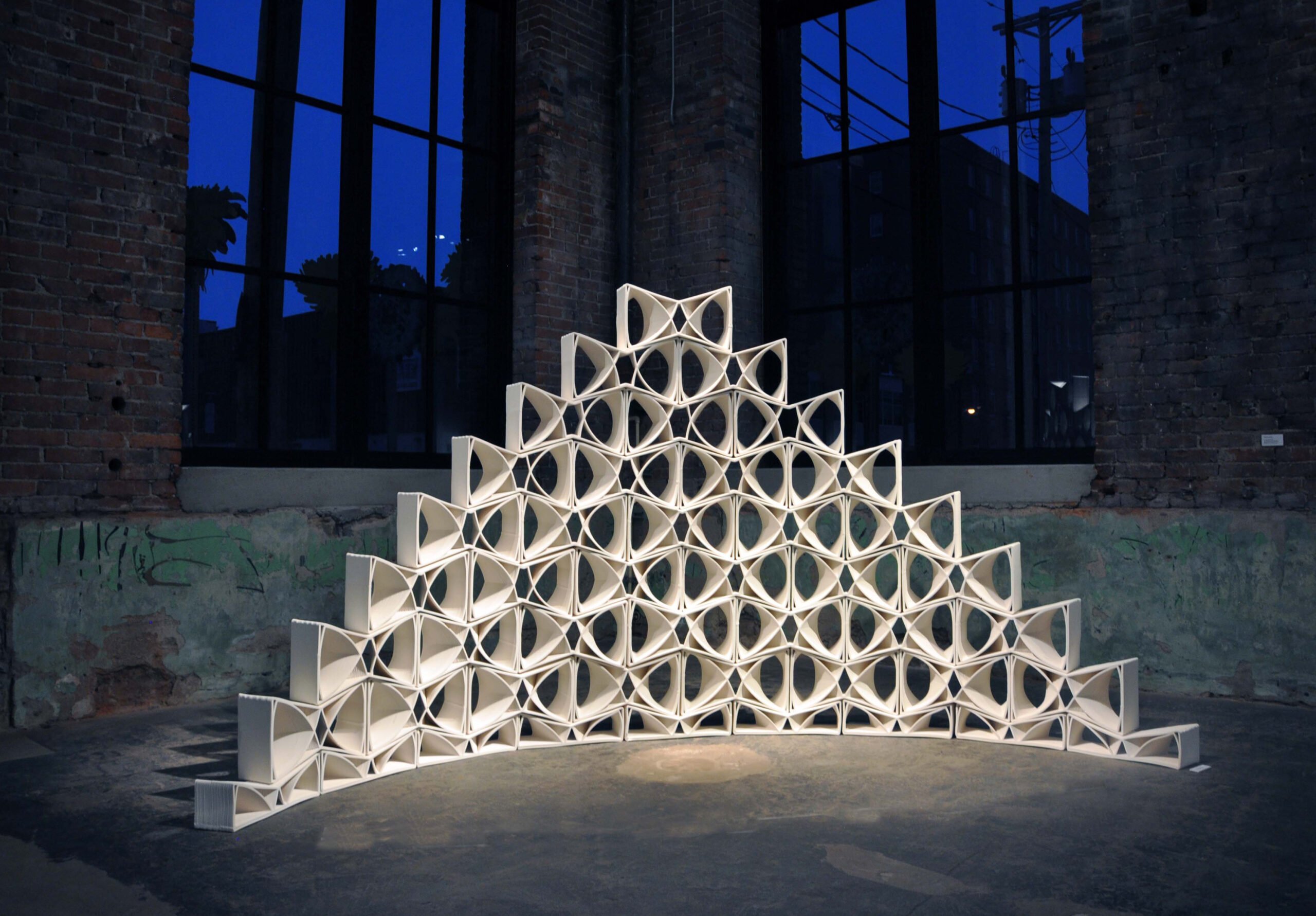

While interior installations provide a little more freedom in terms of finishes and glazes, “exterior options are much more limited in terms of what you can do to make sure it’s going to be weatherproof,” Peters explains. Solar Screen, a permanent installation funded by the National Endowment of the Arts in Youngstown, Ohio showcases the material’s durability. The curved wall is formed by blocks mortared together with solar-powered lights that turn on and off throughout the day, reflecting the weather conditions.

Like Solar Screen, many of Peters’s site-specific installations engage light and shadow, for example, Prairie Cord, a temporary installation at Madison, Wisconsin’s Olbrich Botanical Gardens. Composed of 80 individual blocks inspired by native prairie cord grasses, the cylindrical sculpture sits gently on the surface of a reflection pool, a look that is achieved by an inset wood and steel frame resting on a bed of concrete blocks right below the water’s surface.

“The project took several rounds of prototyping,” Peters notes. “I’m not using a mold, which is a traditional way you make a lot of ceramics,” he explains. “One of the biggest challenges is understanding shrinkage and how pieces are going to deform. Now that I’ve been doing this a while, I know what geometries may or may not work in terms of drying evenly or deforming after they are printed.” At the same time, he has learned to embrace the unexpected in a way that celebrates the idiosyncrasies of 3D printed objects.

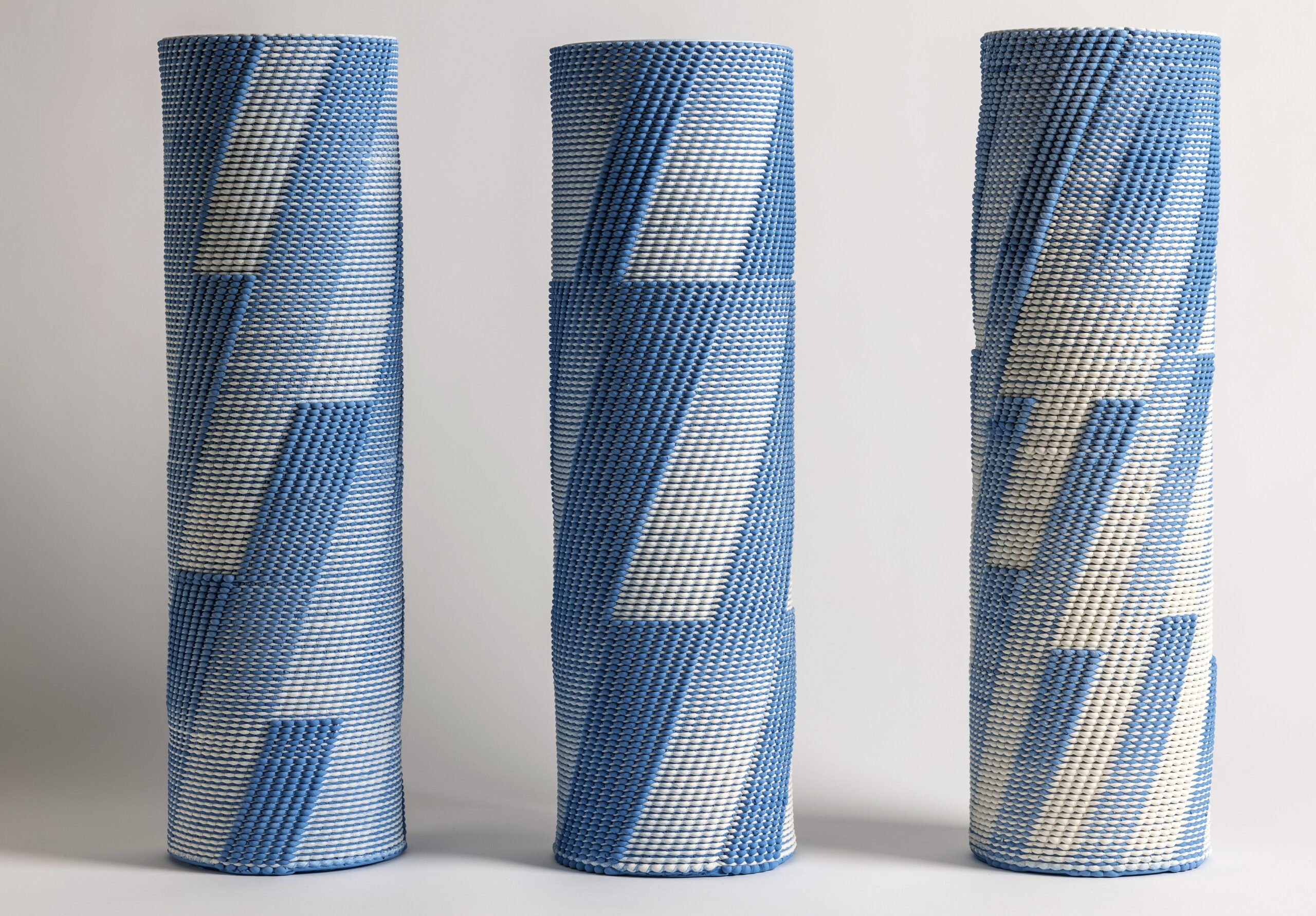

Going forward, the artist is excited to start working with a new printer he built that can print with two different colors of clay, allowing him to weave colors together simultaneously. “[3D printing] is a pretty straightforward, standardized process at this point,” he posits, “But I think it’s going to be about adding more complexity into objects. Everyone’s going to keep pushing the boundary and pushing each other as things go further.”

Would you like to comment on this article? Send your thoughts to: [email protected]

Latest

Viewpoints

How Can We Design Buildings to Heal, Not Harm?

Jason McLennan—regenerative design pioneer and chief sustainability officer at Perkins&Will—on creating buildings that restore, replenish, and revive the natural world.

Products

Behind the Fine Art and Science of Glazing

Architects today are thinking beyond the curtain wall, using glass to deliver high energy performance and better comfort in a variety of buildings.

Profiles

Inside Three SoCal Design Workshops Where Craft and Sustainability Meet

With a vertically integrated approach, RAD furniture, Cerno, and Emblem are making design more durable, adaptable, and resource conscious.