September 4, 2019

In London, a Researcher Guides Biodesign into Uncharted—and Newly Relevant—Territory

With the launch of a new master’s degree, Carole Collet is helping define and advance the rather amorphous discipline.

The word “pioneer” often comes up when people talk about Carole Collet. Since 2001, when she launched the Textile Futures (later renamed Material Futures) master’s degree at London’s Central Saint Martins (CSM) college, she’s been at the forefront of materials innovation, championing sustainable production by extrapolating textiles’ granular, process-led approaches to design more broadly. And with a bevy of research initiatives and the launch of a new graduate program this month, Collet seems primed to maintain this position.

“She exists on a completely different plane of thought,” says Caroline Till, a designer who joined Textile Futures as senior lecturer when Collet was directing the program, later taking on the role herself between 2009 and 2016. “We used to say that she exists 20 to 30, if not 50, years in the future,” she recalls.

Fifty years may not have passed, but it seems that the future is already the present: Not only have the sustainable principles that underpinned Material Futures moved from the fringes of academia to become central concerns within design, but some of the program’s blue sky ideas—from nano- and biotechnology to digital systems and manufacturing data—are becoming reality. Designer Amy Congdon, who is studying for a PhD in tissue-engineered textiles under Collet’s supervision, is among several alumni of Textile Futures who have risen to prominence in recent years. “Carole has been a visionary in how we should be educating the next generation of designers, founding the MA [in Textile Futures] at a time when sustainability was on no one’s radar and changing how people viewed the innovative potential of textiles and materials,” she says.

Collet, who earned her master’s degree in textile design at CSM, says she founded the course to go “beyond the traditional print-weave-knit” framework that textiles training is known for. “They are so much more than that. As a textile designer, if you give me a sheep, I can give you a jumper, because I’ve been trained to transform materials.” Over the past decade, she says, wider swaths of the design world have begun to incorporate this holistic, material-led ethos. “Ten or 20 years ago, designers didn’t design the materials they used, which is what we’ve always done in textiles. Now they create them, too.” Collet is advocating a return to a foundational skill set, focusing on processes inherent in textile craft and encouraging students to think systemically, rather than just about the product at hand. “Who makes it, where is it made, is it recycled? It’s always a very particular ecosystem that has to be analyzed,” she stresses.

Over the past seven years Collet has moved further into research herself, particularly in the somewhat amorphous field of biodesign, which she has pursued since the late 1990s, when she encountered Janine Benyus’s work on biomimicry. “There are parallels between the languages of textiles and biology; in biology we use the terms ‘DNA threads’ and ‘unzipping cells,’” Collet explains. She went on to spearhead a 2008 exhibition at London’s Institute of Contemporary Arts in which designers and Nobel laureates teamed up to look at how biological principles could be incorporated into design. Her contribution, a collaboration with biologist John Sulston, examined the potential of apoptosis—the “suicidal behavior” of cells, which shapes our bodies—to contour objects.

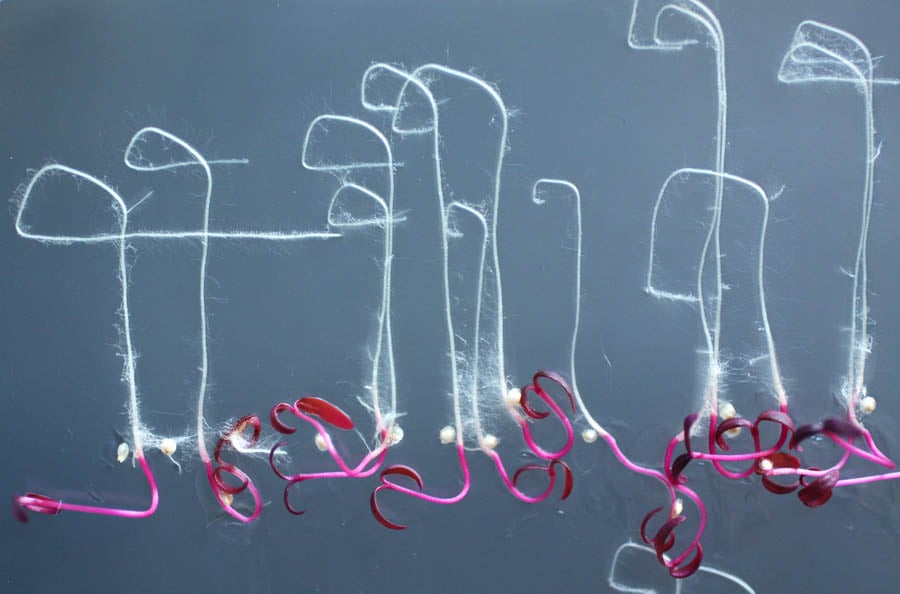

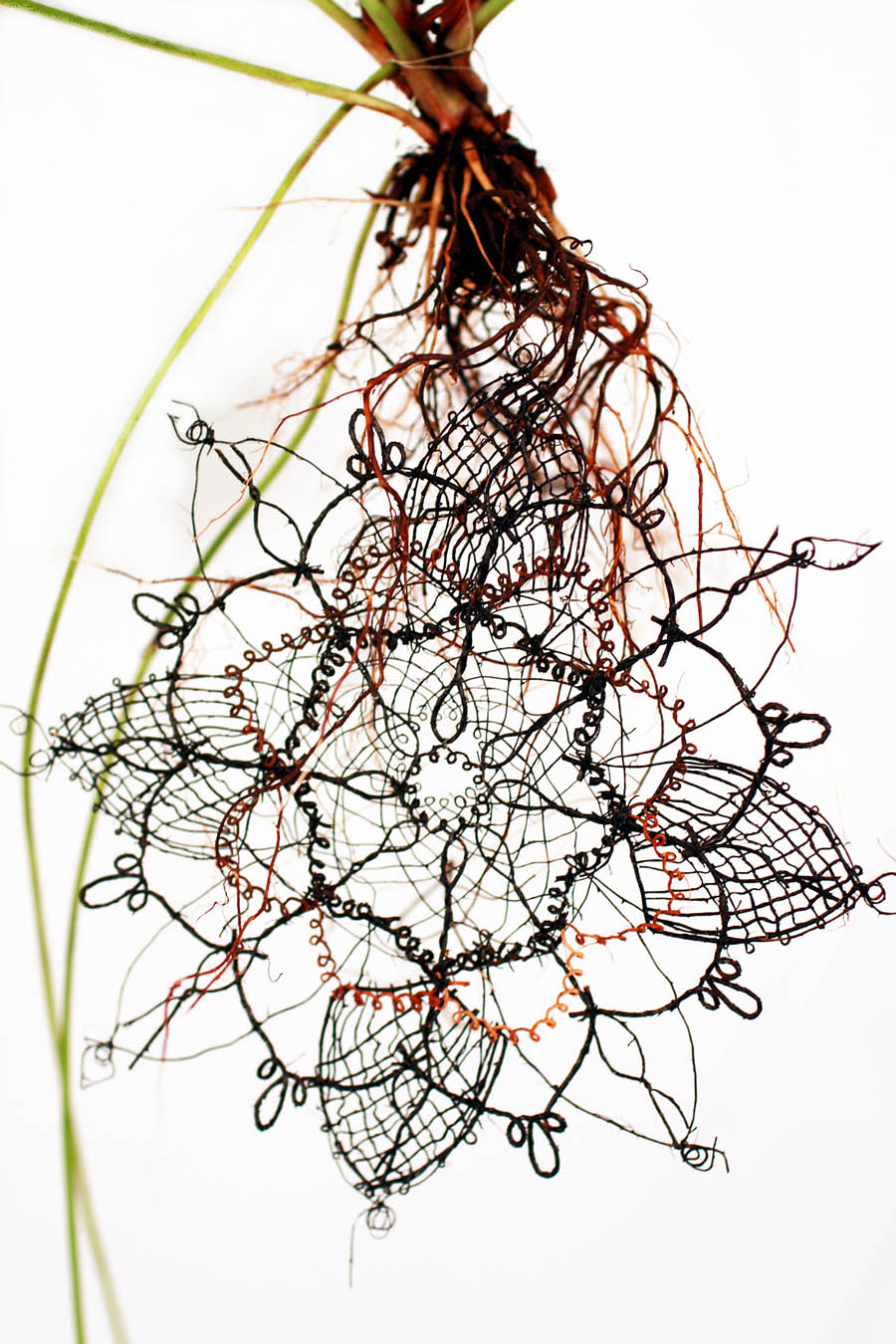

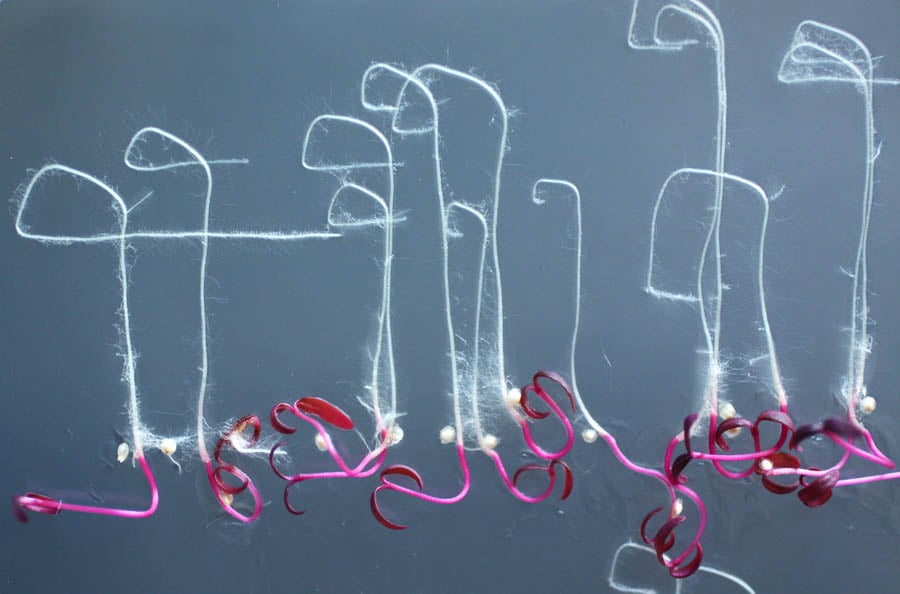

Biodesign, according to Collet, is particularly relevant now. “With systems in nature, there is no waste; everything is interdependent and interconnected,” she says. “We need to learn from that.” Recently, the designer has focused on using mycelium—mushroom roots—to embellish cloth, bypassing oil-based substances. Among the results have been a reinterpretation of traditional tie-dye techniques, called Tie-Grow, and a method for permanently pleating fabric. Building on her 2012 speculative project Biolace, which explored plants’ capacity to produce material and food, she’s turned to tissue-engineering techniques as a means of controlling the development of plant roots, weaving fabric as they grow. A current study imagines plant-grown fur as the basis of new textiles.

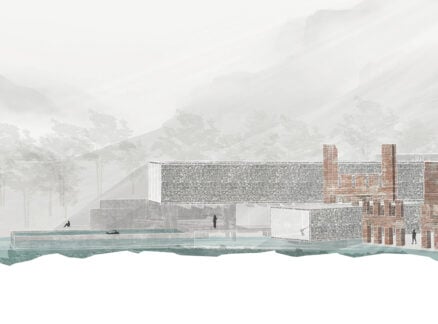

This field of research has been formalized at the university with the launch of the Design & Living Systems Lab, as well as Maison/0, a program for sustainable innovation in fashion, architecture, jewelry, and product design in collaboration with luxury brand LVMH. This month, the launch of an attendant master’s degree in biodesign, led by course leader Nancy Diniz, will feature diverse lecturers, including a biologist, and offer access to a research lab. “We decided that biodesign was moving from being a niche discipline to a more mainstream one, so it was time to teach it formally and assert the discipline within a rigorous academic environment,” Collet remarks.

This interest in biodesign has trickled up to the domain of corporate fashion labels, too. It isn’t hard to see why: Brands are hypersensitive to concerns about diminishing resources, and biodesign presents the tantalizing prospect of a future in which innovative, fit-for-purpose, sustainable materials are grown under controlled conditions. But while such radical thinking may have entered the mainstream, Collet sounds a note of caution: As ever, the viability of these methods is tied to process (how they are made), rather than simply designing for an end result. “Brands are interested in this research, but it takes time to develop new materials that can make a difference,” she says. “The challenge is now how to scale up and test these materials, and finance the research to turn them into something fit for industrial systems.”

You may also enjoy “The Paris Researcher Pioneering a New Way to Recycle Building Materials.”

Would you like to comment on this article? Send your thoughts to: [email protected]