June 6, 2024

At Chapman, Collette Creppell is Redefining the University Campus

Such physical improvements can largely be attributed to Creppell and her staff, which fluctuates between seven and ten people. Since starting in 2019, Creppell has endeared herself on campus with an honest enthusiasm and clear, sensitive vision. Her imposing resume includes degrees at Harvard College and Harvard Graduate School of Design, work as an architect with Rafael Moneo, Moshe Safdie, Ben Thompson & Associates, and Eskew Dumez Ripple; as a planner for the cities of New York and New Orleans, and as campus architect at Tulane University and Brown University.

These diverse experiences—not to mention her childhood as an Air Force brat, exposed to urban fabrics around the world (her family avoided bases in favor of denser environments)—have helped shape a vision based on craft, criticality, and what she calls “a sense of discovery in the existing condition.” Wherever she is, she doesn’t need to start from scratch. She knows how to make a place out of what’s already there.

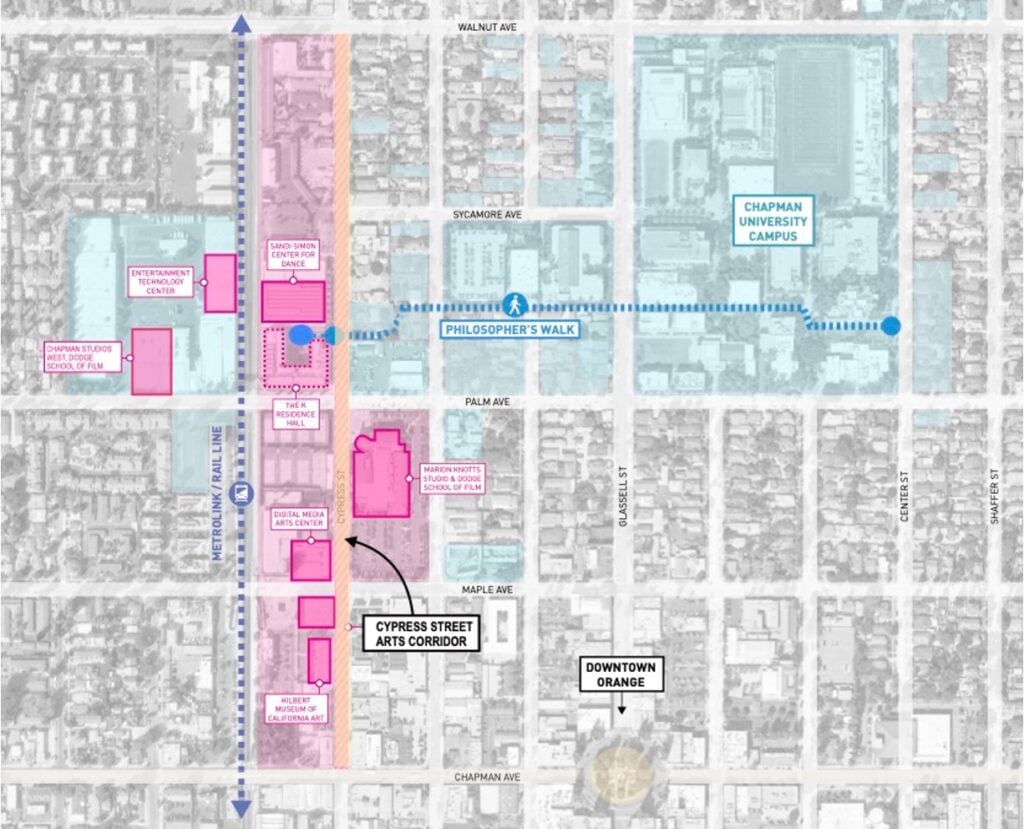

Creppell came to Chapman largely because the school entrusted her with a broad, ambitious vision. It’s not about growing as fast as possible—the typical model in Orange County, and much of Southern California—but holistically improving, renewing, and connecting the campus, which stretches lengthwise from its dense, historic core to the east to its emerging Cypress Street Arts Corridor, containing arts-related departments and cultural facilities, to the west. “You’re exploring the campus that you have,” says Creppell, “and linking it in more interesting ways.” She is also working to make a genuine place out of a series of blank office parks in Irvine, about ten miles south, creating Chapman’s new Harry and Diane Rinker Health Science Campus. (More on that later.)

“I have a passion for making genuine urban spaces. This seemed like a place I could do that happily, and be very well supported” notes Creppell. That’s thanks largely to university president Daniele Struppa, a decorated mathematician who considers building to be as much about conveying meaning as it is about practicality. “She understands the presence of space and the absence of space, and the use of design to convey values and inspire people,” says Struppa. “She’s taking the campus to a new place.”

A plan of Chapman’s evolving campus, shows the two axes being defined by Creppell and her team—the east-west Philosopher’s Walk and the north-south Cypress Street Arts corridor.

To help unify the campus, Creppell and her colleagues have started work on what they call the Philosopher’s Walk, an east-west connector (inspired by Kyoto’s ancient Philosopher’s Walk) that will be carved via new footpaths and landscaping and the re-routing of parking lots, drive lanes, and, in at least one case, buildings. She’s working to better establish the school’s relatively undefined central swath via new structures and renewed historic ones, and her team is undertaking the “Water-wise Landscape Project, already replacing more than 25,000 square feet of turf with varied California-native, draught-tolerant plantings.

But the Cypress Street arts corridor, edging the city’s railroad tracks, is, for now, the center of Creppell’s work. A former industrial zone (part of the Cypress Street Barrio, a historic Mexican-American community) once catering to the processing of the city’s namesake, oranges, it’s becoming home to a number of unique adaptive reuse projects for Chapman. This includes LOHA’s Sandi Simon Center for Dance, located in a former orange packing warehouse, Johnston Marklee’s Hilbert Museum of California Art, situated in two former auto repair spaces, and EYRC’s Killefer Institute for Quantum Studies, sited in a 1930’s schoolhouse.

These projects’ respect for both past and future, says Creppell, while relatively novel in Orange County (it’s hard to find a local builder with adaptive reuse experience, she notes) is a hallmark of her approach. “I’m from New Orleans, we revere our ancestors,” she says. “But to honor our ancestry, we need to be relevant for the next 90 years.” This is something that Struppa, who hails from Milan—a city that has long balanced the ancient and the modern— inherently respects as well. The approach is also a vital step toward reducing the school’s carbon footprint, she adds, and helps foster goodwill with vocal local preservationists and neighbors. Her selection of architects, meanwhile, leans toward “superb designers who are also thinkers who have curiosity and humility.” No ego-filled, wholesale destruction here.

The Arts Corridor had begun development prior to Creppell’s tenure, containing impressive reuses like AC Martin’s Digital Media Arts Center (2014), a transformation of the brick and concrete California Wire and Cable Co. (1922). But this wave of work has elevated this template to a new level.

LOHA’s Sandi Simon Center, the first of the new crop, has helped build momentum, and trust, for the next endeavors, Creppell notes. She and I park the golf cart to have a look. Outside, the two-story, blond stucco shell of the utilitarian building, marked by long metal canopies and an old “Sunkist” sign, remains intact, helping it mesh with the neighborhood; as does a sunken plaza, which connects to an adjacent student residence. But inside it’s a new world—a luminous, three-story space dramatically opened via digging into the building’s basement, removing internal columns, and shoring up enormous roof trusses. Natural light streams in through the original sawtooth roof, clerestory windows, and translucent polycarbonate walls. Various-sized rehearsal and performance spaces curve and flow through the building, evoking the movement of dancers, as do interstitial walkways, walled with wood from the warehouse’s original floors, with sizeable custom benches and cushions creating popular hangout zones.

“How do you make it about the in between spaces?” notes LOHA founder Lorcan O’Herlihy, who wanted the facility to be as much about building and celebrating community as it was about dancing. “When it opened the students just flooded into the space. They loved it. They were literally running around,” he gushes.

Just south of Sandi Simon, workers are putting the finishing touches on Johnston Marklee’s Hilbert Museum of California Art at Chapman University, conceived as a western gateway to the school, which opened on February 23. Founded by philanthropists Mark and Janet Hilbert, it contains the world’s largest collection of California Narrative Art, including one of the world’s largest private collections of Disney art. Facing the city’s train station, just to its west, the museum’s two beige, stucco-clad, tilt up concrete boxes frame a concrete tiled courtyard (formerly an asphalt driveway), enlivened with raised and projecting volumes and grey columns and softened by a large central oak tree and lush peripheral landscaping by SWA.

The first thing one sees from the train is Pleasures Along the Beach, an exceptional 40×16 foot 1969 mosaic by the renowned California artist Millard Sheets. Depicting swirling, fiery-toned seagulls, beachgoers, ocean, and mountains, it was moved (piece by piece, by Millard Sheet’s son Tony and Brian Worley, one of his former associates) from the former Home Savings and Loan bank in Santa Monica. Inside, spaces—including 26 galleries—are elegantly organized with world-class art, but the feeling is more low key than a typical art museum. Concrete floors, exterior walls, and acoustical tile ceilings are evidence of the museum’s first iteration, in 2016, by San Dimas, CA-based Aday Architects, not to mention the original workaday buildings. All is layered with light courts, museum lighting, and other clues that this is a world class collection.

Johnston Marklee principal Mark Lee discusses his firm’s effort to preserve the buildings’ roughness, and even celebrate their plainness. “There’s a certain blankness about many early Southern California Buildings that is charming. Rather than overly gentrifying, we thought we could amplify this kind of beauty,” he said. The firm sourced as many local materials and furnishings as possible, added senior associate Lindsay Erickson.

Creppell and I park the golf cart and head to the dirt-filled construction site of the newest addition to the arts corridor: the home of Chapman’s Institute for Quantum Studies and Advanced Physics Laboratory. This project reuses a much more precious historic structure: the Killefer school, a national landmark that in 1944 became one of the first schools in California, and the country, to desegregate. (It occured ten years before nationwide school desegregation.) The Spanish Colonial Revival edifice, topped by an eight-sided belltower, had sat empty since closing in 2004, and still reveals what had been severe deterioration and vandalism. But it will soon contain new classrooms, research spaces, common areas, an auditorium, and a historic exhibition space, not to mention a two story laboratory addition.

The team is preserving as much of the original building as possible—walls, window sashes, even old chalkboards—while creating a modern facility that meets today’s codes and the needs of its academic users. Around its edges three courtyards will serve as outdoor rooms, supporting deep thinking, congregating, and events. The addition, clad in scratched stucco and red tile, defers to the landmark original structure, set back from the street and folding inward at points, almost as if it were bowing to its historic neighbor.

This is not the typical hefty, hermetic science building, says EYRC partner Patti Rhee, who acknowledges that an old schoolhouse would not be the first choice for most quantum physics departments. “It forces you think more creatively. It encourages people to rub elbows and be in contact with what’s around them. And it gives the space a significance that you just can’t make.”

Rhee admires Creppell’s ability to dig into existing fabrics and find what’s unique and authentic, rather than creating a systematized “look” for Chapman. “There’s not just one way to do things,” she says. “By bringing in such disparate types of approaches I think it leads to a richer experience.”

At Irvine’s Rinker Center, the conditions for transformation are drastically different— not an existing campus and town, but a series of placeless, sprawling office parks. Yet Creppell and her team are pulling from the context here as well—only before it was paved over and homogenized.

She talks about the broad coastal plain stretching from the Pacific Ocean to the Santa Ana and Santiago Mountains, which still cradle Irvine. She lists plants, wildlife, and rivers that still, somehow, exist here. The work here is just beginning, but already she’s worked with landscape firm Link Inc. to create a wide plaza planted with a mix of native and medicinal non-native plants, stitched together with bands of planting, paths, and concrete and wood benches. This leads to LPA’s new Campus Center at Rinker—a former tilt up concrete building that has been opened up with glass walls, centered around natural materials and fine art (from the school’s Escalette collection, whose artworks can be seen all over campus), filled with focused study and collaboration spaces, and oriented toward the mountains. New hanging banners, created by a Chapman student, reference local plant life.

Rinker’s Framework and Vision Plan, which has evolved over the last 3.5 years, was created by Creppell along with consultants that include JFAK, KTGY, LPA, Link, Inc, and Design Workshop. It calls for creating more active, open buildings and replacing parking lots with continuous landscapes, nodes and pathways. The plan also lays out public art, framed green spaces, bridges, and tall markers like campaniles. Not all has been approved, but much of a nearby parking lot is about to be replaced with public space, starting the next phase of the project.

“She’s set the tone,” says JFAK co-founder Alice Kimm, who was a classmate of Creppell at the GSD and praises her holistic vision. “The big picture is her strength.”

It’s a level of focus, ambition, and sophistication that few schools in the region are achieving, including local powerhouses like USC and UCLA, where either modern architecture has been sidelined (USC) or little space remains on campus to create significant new conditions (UCLA). “It’s encouraging that she keeps pushing,” says O’Herlihy.

For Creppell, “good” means resonating with the meaning and relevance; something that can only be achieved via deep study and observation. She likens she and her colleagues’ reading of context to Renaissance painters using underpainting to create vibrancy. “The hidden or barely visible underlayer comes through in the energy of the painted surface,” she notes.

Would you like to comment on this article? Send your thoughts to: [email protected]

Latest

Projects

The Project That Remade Atlanta Is Still a Work in Progress

Atlanta’s Beltline becomes a transformative force—but as debates over transit and displacement grow, its future remains uncertain.

Profiles

WAI Architecture Think Tank Approaches Practice as Pedagogy

Nathalie Frankowski and Cruz García use their practice to help dismantle oppressive systems, forge resistance spaces, and reimagine collective futures.

Products

Functional Beauty: Hardware That Does More Than Look Good

Discover new standout pieces that marry form and function, offering both visual appeal and everyday practicality.