April 26, 2023

Namita Chandrashekar Designs for Harmony with the Natural World

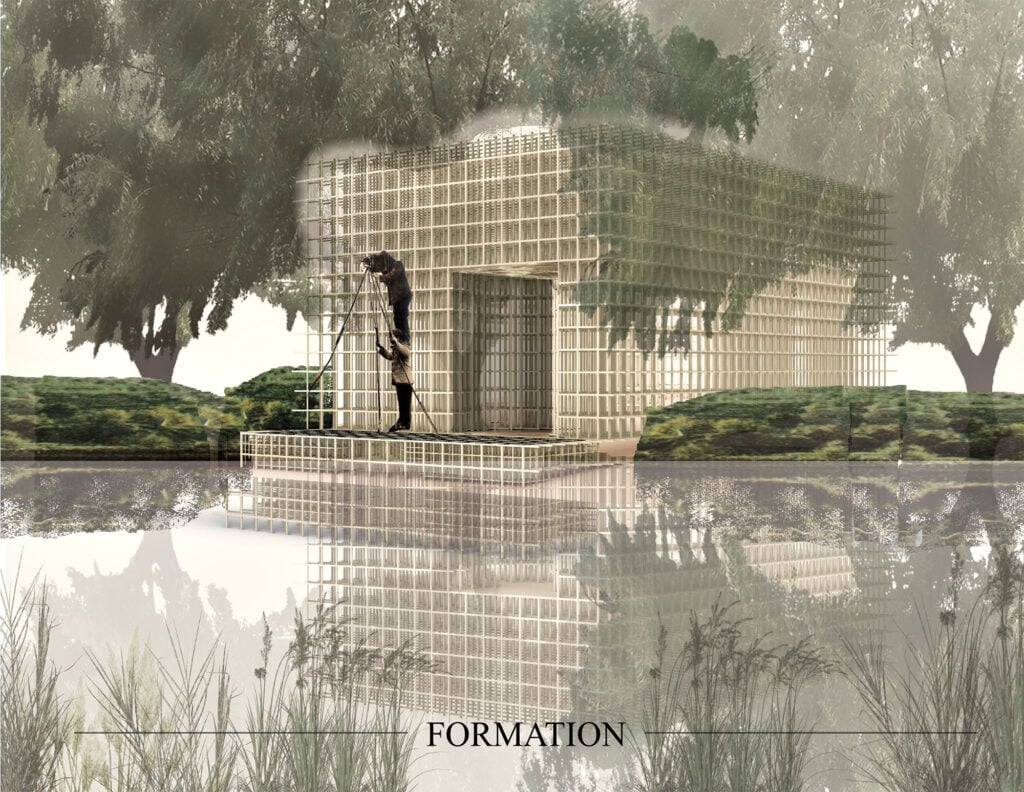

Good public design rarely relies on angles or color schemes—it’s the cultivation of community that defines success. This concept is inherent to the practice of Namita Chandrashekar, who trained as an architect in bustling Mumbai before moving to New York City to complete her master’s of fine arts in interior design at The New School’s Parsons School of Design. With her project Incandescent Immersion, the young designer reimagines an urban interior within Central Park as a refuge for “the human and the nonhuman life forces that interact with the built environment,” she explains, creating an immersive structure that blends with nature rather than fighting it. “This urban pavilion tends to different definitions of interiority, allowing the scale of the grid to respond to the agents’ needs, be it a bird, human, tree, or light.”

Inspired by the idea of letting nature be a co-creator in the process of design, Chandrashekar composed this lamp out of banana leaves. She used traditional weaving practices along with cornstarch as a natural glue to hold the free ends of the weave in place. COURTESY NAMITA CHANDRASHEKAR

Designing in Partnership with Living Materials

The rich textures of nature are abundant in Chandrashekar’s work. In Thrissur, a material exploration in birch plywood and banana leaves, the flat, hearty fronds are woven into a series of traditional floor tables, crafting an homage to the ubiquitous banana leaves used in family celebrations and holiday festivities in South India. In Weave, the same leaves are transformed into a biodegradable lamp prototype. “When you let nature be a co-creator in the process of design, the outcomes are far more beautiful,” she says of working with sustainable materials like peace lilies and fallen ginkgo leaves. “I have seen projects bloom to life by incorporating a natural element,” she says, explaining that “you learn to be more delicate and nurturing when you are using living materials, as there is so much you cannot control.” In addition, Chandrashekar notes that when you listen and respond to the needs of your material, the process is elevated to one of partnership. “You are no longer driving the project but collaborating with the materials.”

This urban pavilion in Central Park is designed as a refuge for human and nonhuman life forces. The project aims to create an interior space that coexists with the natural world. COURTESY NAMITA CHANDRASHEKAR

Would you like to comment on this article? Send your thoughts to: [email protected]

Related

Profiles

Zoha Tasneem Centers Empathy and Ecology

The Parsons MFA interior design graduate has created an “amphibian interior” that responds to rising sea levels and their impacts on coastal communities.

Profiles

Future100: Lené Fourie Creates Adaptable Interiors

The University of Houston undergraduate student is inspired by modular design that empowers users to shape their own environments.

Products

Four Creatives Harnessing the Energy of the Sun

Designers Shani Nahum, Pauline van Dongen, Yvonne Mak, and Mireille Steinhage are imagining a future where solar textiles are the norm.