August 4, 2017

Giving Designers the “Star Treatment” Began with Olga Gueft

In the 1950s, the editor-in-chief of Interiors magazine devoted pages upon pages to three designers in particular.

This is the third in a series of articles (first and second installments) on Interiors magazine editor Olga Gueft (1915 – 2015), a pioneering champion in the history of the interior design profession.

As the editor of Interiors, the most important interior design industry magazine of its day, Olga Gueft always published the best, most innovative work she could find. In reviewing the magazine archives, starting with her tenure in the 1950s, it becomes clear that Olga favored the work of AID members (American Institute of Decorators, the primary professional organization for interior designers at the time); these were women, industry veterans, pioneers, and newcomers.

Of all those whose work graced the pages of the magazine, there were three practitioners who appeared in Interiors more than any others: Florence Knoll (1917–), Edward J. Wormley (1907—1995), and Melanie Kahane (1910—1988). The most prolific of the group, whose name remains well known among today’s designers, is Florence Knoll, architect and interior designer, and the innovative work of her Knoll Planning Unit, an arm of the Knoll furniture company. Edward Wormley, AID member, is best known for his 30 years of furniture collections for Dunbar. Melanie Kahane, another AID member who was an elected officer in the association, was famous for her colorful interiors. (Kahane became a member of Interior Design magazine’s Hall of Fame in 1985.)

The Good Planner

Knoll who, in 1946, founded Knoll Associates with her husband Hans, was a singular pioneer in interior space planning. A Modernist who studied as well as worked with legends like Eero Saarinen, Ludwig Mies van der Rohe, Walter Gropius, and Marcel Breuer, she saw the postwar building frenzy coming and seized on the opportunity, founding a complete design service to the furniture company’s clients. The Knoll Planning Unit was a revolutionary idea for the industry and perfectly in line with the high demand for efficient, flexible, and modern furniture designs for business. Knoll and the Planning Unit worked closely with clients to understand their businesses, how they operated, and how much space they needed to do their work. In 1956, Knoll was working on the interior design of the Connecticut General Life Insurance’s new headquarters outside of Hartford, when she noticed some large inefficiencies in space allocation. She challenged the client’s assumption that a basic individual office needed to be 12-feet-by-18 feet. She was an early proponent of creating full-size mockups of private offices, workstations, and circulation corridors to demonstrate the benefits of good planning.

For Connecticut General, Knoll created a 72-foot-by-60-foot full-size mockup to show the client how the office interiors might be organized, partitioned, and furnished. This also proved her argument that the smaller, 12-foot-by-12-foot basic office was both “completely efficient” and “psychologically uncramped.” But Knoll’s planning talents are not her only legacy. This energetic woman, who turned 100 this May, is also responsible for bringing to market many iconic furniture designs: Mies van der Rohe’s Barcelona Chair, Eero Saarinen’s Womb Chair and Tulip line, and Harry Bertoia’s wire chairs.

The Designer of Versatility

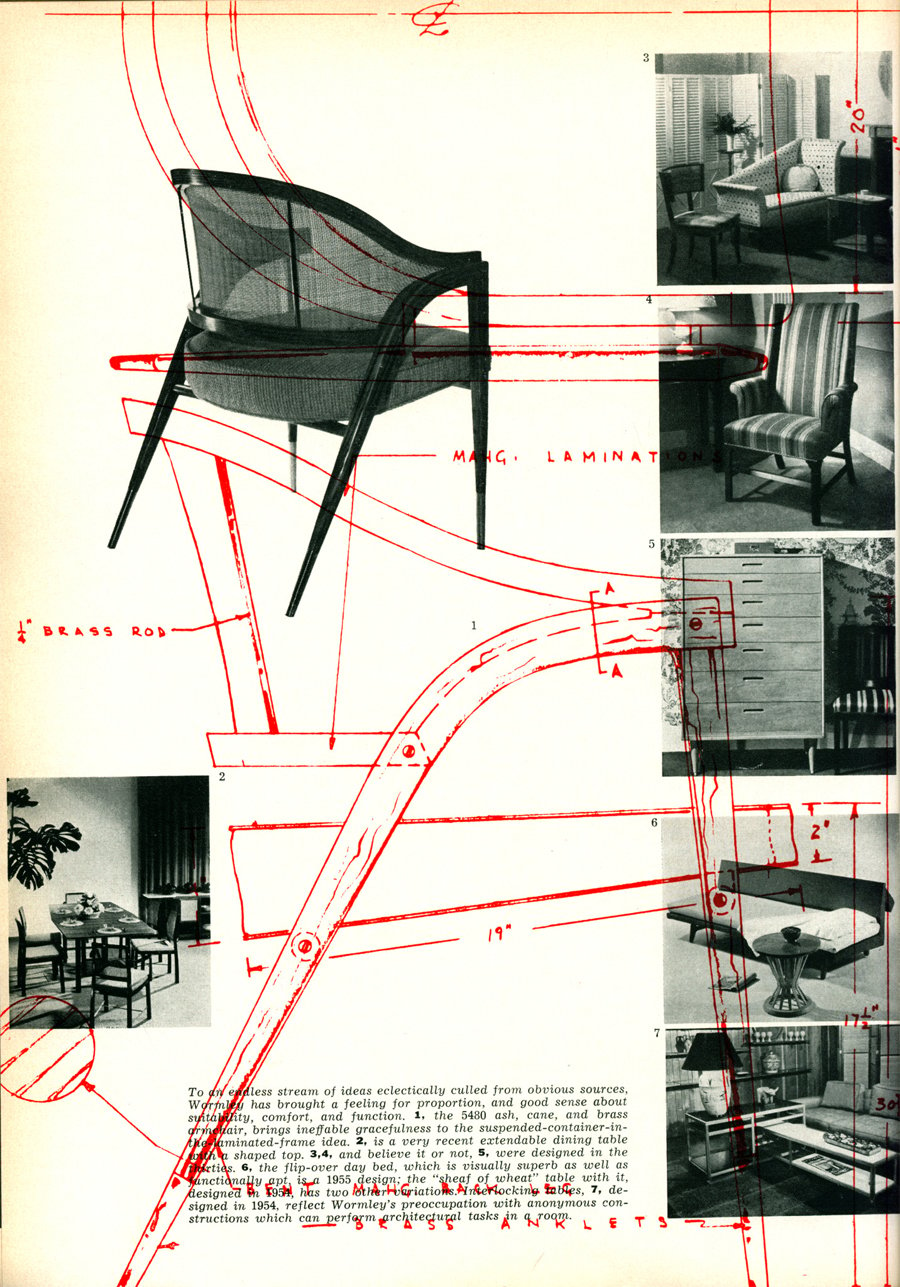

In November 1956, Interiors devoted an unprecedented 14 pages (including color photos, a rarity at that time) to a profile of Edward J. Wormley who was celebrating his 25 years as design director for the furniture manufacturer Dunbar. Olga described him as “one of the most important furniture and interior designers of our day.” And although many mid-century furniture designs derived strongly from the work of pioneering designers like Hans Wegner, Charles and Ray Eames, and Saarinen, Wormley’s works transcended many of the characteristics of the period. He re-interpreted classical tradition with a modern eye and an appreciation of variety in all things. His furnishings did not evince a signature style, but one of diversity in form and function. Over the years, Wormley designed everything for interiors from rugs, lamps, and fabrics to music stands and displays.

By his own admission, his influences included many of the great designers in history: “Riemerschmid, William Morris, Finn Juhl, and Alvar Aalto.” Not surprisingly, Wormley also began to design offices, taking advantage of tremendous opportunities available to a designer of such versatility. Both his residential and commercial interiors showed his reverence for modernity and history. Wormley often liked to mix his modern Dunbar furniture with antiques, accessories, and materials that showed great richness of expression and variety. Based on my research, he appears to have been among the first interior designers who purposefully mixed furnishings from different time periods and places in much the same way that we do today.

The Tastemaker

Melanie Kahane was a trend-setting designer and a leader in the AID. She worked in both the residential and contract realms. Olga featured a short profile of Kahane in the June 1954 issue as part of a promotion about professional designers who read Interiors. It proclaimed that “manufacturers, industries and editors know Miss Kahane’s lively news sense and sound grasp of merchandising value make her a designer whose ideas, used in promotions, start trends … lift the public taste … and sell a whooping lot of merchandise.” But, unlike the masters of social media today, Kahane did not use her design and marketing prowess just to sell product and make money. She believed that “design is a way of living” and wanted to show Americans “how to live better.”

One reason for Kahan’s tastemaker status may be that she frequently participated in model room exhibitions, the 1950s equivalent of today’s designer show houses. The exhibitions were often sponsored by the AID, furniture marts, new apartment buildings, and manufacturers. More importantly, these venues were generally open to the public. Bolstering her appeal as designer, Kahane often used bold color in her interiors but did not devote herself to a single style or signature look. She believed in both modernity and tradition.

Olga promoted the work of many designers during her long reign as editor. In the 1950s articles about Finn Juhl, Raymond Loewy, George Nelson (also an editorial contributor at Interiors), William Pahlmann, and Everett Brown all appeared. Over time, Olga increased the magazine’s coverage of international design work significantly. Even though this was often difficult to do at the time, she set out to search the world to bring good design to her devoted readers.

Sylvia Sirabella is a graduate student at the New York School of Interior Design and an Interiors Intern at HOK. She has been reading the Interiors archive for the years during Olga’s editorship to establish her contributions to the history of the interior design profession. Before becoming a designer, Sylvia was a full-time mother and a credit specialist and vic epresident at Citigroup’s Private Bank. She can be contacted at [email protected]. This research was funded by a grant from the ASID Foundation.

If you enjoyed this, you may want to read the previous articles in this series, “From “Decorators” to Designers: How Olga Gueft Helped Evolve the Interior Design Profession” and “Rediscovering Olga Gueft, Foremother of Interior Design.”