January 16, 2024

How Can We Rethink Architecture and Design Models?

Every day, there’s a new reminder that climate change and growing inequities are catastrophically changing how we live. Humanity is at a tipping point, and mending our communities and finding new ways to thrive are imperative for a viable future. So, not long ago, I shifted my career to focus on the systemic and social issues that contribute to the climate crisis. And in doing so I’ve discovered many others in the architecture and design professions who have similar priorities.

Alternative Practice is a new initiative I’m launching with Maya Bird-Murphy, an architectural designer and founder of Mobile Makers, in response to our shared frustrations about the state of the design field and our world. To change current realities, we have had endless conversations about colonialism, white supremacy, patriarchy, capitalism, houselessness, disinvestment, environmental degradation, and the lack of agency and resources of individuals and communities. There seems to be a shift afoot—a reprioritization of values that drive business (and design solutions); the centering of love and gratitude, valuing the collective over the individual, embracing slowness, and challenging growth. We want to know more about the practices, agencies, labs, collectives, and research teams that are operating outside traditional modes and leading this shift. We aim to collect, archive, and share the knowledge held by the hundreds such alternative practices that exist today so designers can ultimately create liberatory futures for all.

At the end of September, I moderated a panel talk at The Design Summit for Friends of Friends in Chicago, an interdisciplinary event focused on change-making in design hosted by Mobile Makers. The discussion, also titled “Alternative Practice,” brought together three designers whose practices challenge the status quo. We invite you to join the conversation.

Multicontextual Design by Duo

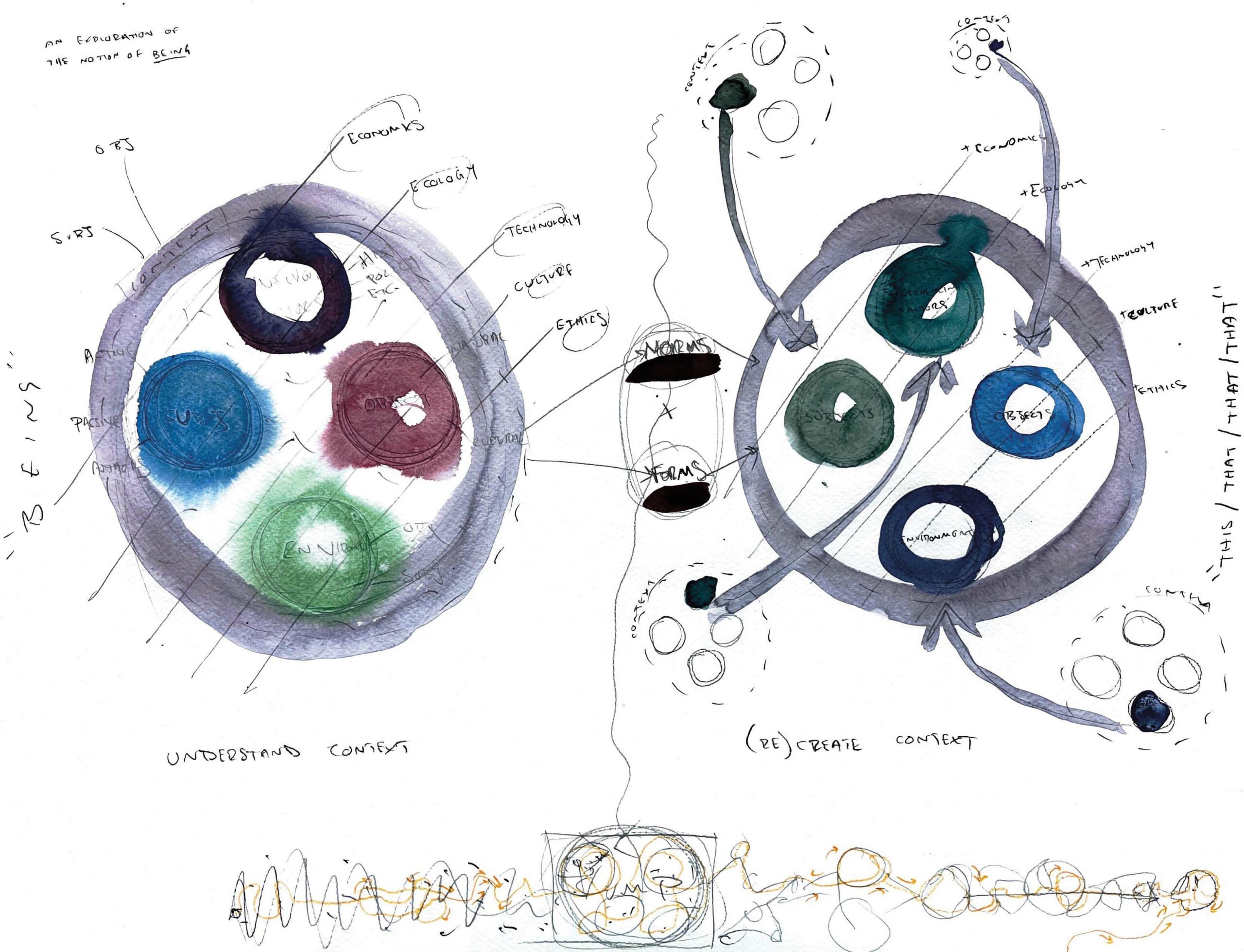

Verda Alexander: Rafa Robles is the cofounder and director of Duo, a studio/lab that works to create built-environment innovations for the benefit of society. Rafa, you have defined a term, “multicontextual design.” Can you tell us what that is?

Rafa Robles: Sure, it‘s a term that my brother and cofounder Carlos came up with. He’s in public policy and my background is design. We felt like a lot of our conversations were leading to a place that we couldn’t really define. The philosopher Cornel West describes himself as a “multicontextual intellectual” because he can inhabit a lot of different spaces in different ways. We were like, “Huh, that could be interesting for a design practice.” Often in design, if you work on housing, then you have to explain how your project is going to solve the housing crisis. If you work on a sustainable building, you must explain how that’s going to solve climate change. We feel like that’s not productive, not realistic, and it often just stops a lot of projects from happening. In our practice, we rethink the norms in those projects and then give new form to alternative realities that promote other ways of practicing, inhabiting, and owning spaces.

Studio Elsa Ponce and Community Access

VA: Elsa Ponce is a Mexican-born architect, interdisciplinary designer, and educator based in Brooklyn. She leads Studio Elsa Ponce, a research-based design practice that challenges hegemonic processes toward spatial justice and community access. Elsa, you describe yourself as a professional between places?

Elsa Ponce: There’s this duality that I feel is very important to my practice and the way that I think that there’s not one absolute truth. I think having that philosophy of being between places, I also share it with the communities that I work with that are mostly immigrant, and that’s also a connection that I really value. I reflect myself in them, and through my work. I like not being at the center of anything. I’ve always tried to avoid any labels: I consider myself an architect, but I’m also an educator and a designer and a mother. We are multifaceted. It’s been a journey and I am comfortable with the idea of not being anywhere.

Alternatives from SOCA

VA: Tura Cousins Wilson is an architect from Toronto and cofounder of the Studio of Contemporary Architecture (SOCA), working in a variety of scales and building types. Tura, why is research and speculative work so important to you?

Tura Cousins Wilson: I have always been interested in pushing ideas that we might not be able to explore in a traditional model. We’ve been pushing ideas for alternative processes, particularly in communities that don’t know what architects do, or may not be able to afford an architect. In Toronto, our focus was on a Little Jamaica community which was hit by gentrification exacerbated by a new transit line that’s accelerated displacement. We’ve been working on developing alternative housing models, and in this case a community land trust both for the residential and the commercial community, understanding you need both to create a vibrant community.

Discussing Alternative Practices

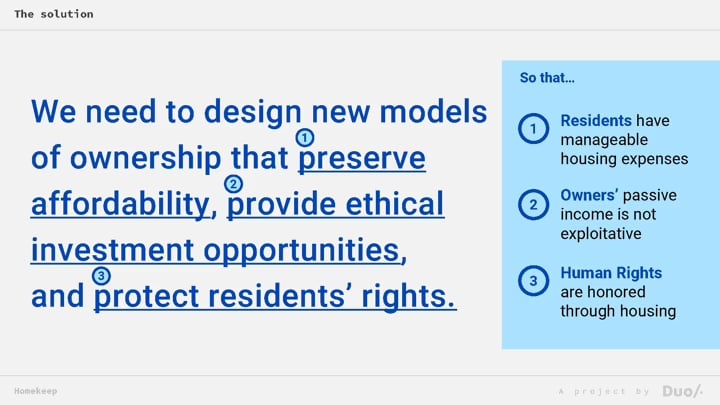

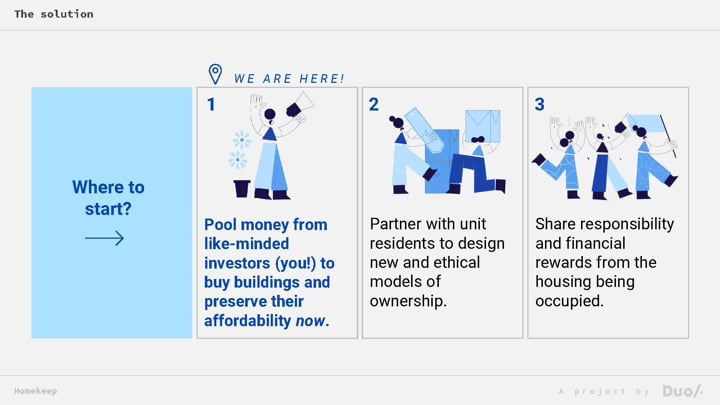

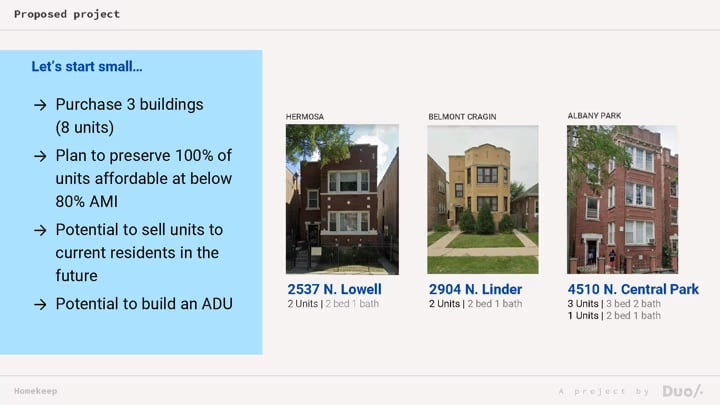

VA: Now, Rafa, you’re working on different economic models to housing too. Many of your projects come from thinking about new realities. Instead of solving the problem in front of you, you’re thinking about the result that you want, and you were able to explore these new models of ownership and tackle housing affordability with the project Home Keep.

RR: I think less about what problem am I solving, which is a very business-driven mechanic way of looking at it. And we think more about what reality [we are] creating. We didn’t want to just keep acquiring more affordable buildings. We really wanted to tackle the question of why aren’t these units affordable in the first place? What if we imagine a world without landlords and tenants, what would that look like? And when we talk to developers, they’re like, “That’s crazy. I’m always going to be a landlord.” And we’re like, ”We’re going to make sure that you’re not.” Some of the people have lived in their units 20 years and have zero equity in their buildings; we think that’s wrong. In our practice, we really push ourselves to imagine a new reality. Then we try to make it happen.

VA: It’s like you’re looking for a solution and doing it within and outside the capitalist system. Amazing. Elsa, as an architect, you talk about not building buildings and the value of impermanence. What is architecture without architects?

EP: Impermanencias, which means “impermanences,” is a research project that I started in Mexico City. It’s a project where I had no client, just an impetus. I got funding from Mexico’s National Fund for Culture and the Arts, and the project started by looking at how empty our cities are. I was interested in why we have so much space. Why do we keep building buildings? I was curious to investigate how people get organized and collectively do something in a space. Permanence is overrated. We are taught to design buildings that stand for a long, long time to the detriment of the environment and inflexibility of use. It’s very hard to convert a building, and building as a permanent exercise is not sustainable anymore. I formed a network of people in Mexico City: activists, designers, artists, architects, and organizers. I observed how they were using space, then I started mapping and drawing networks. Just by looking at how they were using space we were able to understand resources that they could use in a provisional or impermanent way.

VA: Elsa, you’re part of another practice called WIP Collaborative. It has a double meaning: work in progress and women in practice. It’s nonhierarchical. Why does nontraditional practice appeal to you?

EP: The experience of practicing as an architect was brutal: the amount of work hours, the pay, and the relevance. I felt that I was never going to meet the users of many of the spaces I was working on. It was not a very collaborative effort. I joined a community of women and we started to have very candid conversations, asking questions like, What’s the situation at work? How are you feeling? Do you feel like you’re compensated fairly? Do you feel like you are promoted to roles that are significant to you? And through those conversations we started to think about whether there was another way of practice that was nonhierarchical, where we could share the workload and also share situations of life. If one of us became a mother, can we have a communal day care? We started imagining new realities of what a feminist practice could be.

VA: How have your experiences at other firms as well as your personal values and the missions of your organizations influenced the internal operations of your personal practices?

TCW: To a degree, I think it’s just about allowing people flexibility, and that requires a lot of trust. It’s also about nurturing enthusiasm about the work we’re doing. Ultimately, [we care] if people are happy and can communicate as a team.

RR: We need to prioritize ourselves and be intentional about the decisions we make. We talk a lot about liberation, like, “What do I really want to do every day and what does Carlos want to do every day and how do we do more of that?” I think of self-empowerment too: If we came up with our own projects, what would they look like? We want to set a new precedent for work so that we’re happy day to day. And then if it inspires other people to do that too, then great.

EP: I think the collaborative model might be more interesting to learn from. We call it Work in Progress because we are figuring it out. It’s important for us to set the expectation that things are evolving. We don’t want to have all the answers right away. Sometimes the client might not be appropriate for our values. Equity and choice are important values that we think about when we are making decisions. You can choose what to work on, the number of hours, and within what capacity. There are always two co-leads on a project in case somebody needs to step out for a work or family emergency.

VA: I think that’s a great way to close—this idea of intersectionality and all the things that bring us joy, including the work that we do. It is a journey and we are constantly learning. Thank you, everyone!

Would you like to comment on this article? Send your thoughts to: [email protected]

Latest

Profiles

BLDUS Brings a ‘Farm-to-Shelter’ Approach to American Design

The Washington D.C.–based firm BLDUS is imagining a new American vernacular through natural materials and thoughtful placemaking.

Projects

MAD Architects’ FENIX is the World’s First Art Museum Dedicated to Migration

Located in Rotterdam, FENIX is also the Beijing-based firm’s first European museum project.

Products

Discover the Winners of the METROPOLISLikes 2025 Awards

This year’s product releases at NeoCon and Design Days signal a transformation in interior design.