May 16, 2019

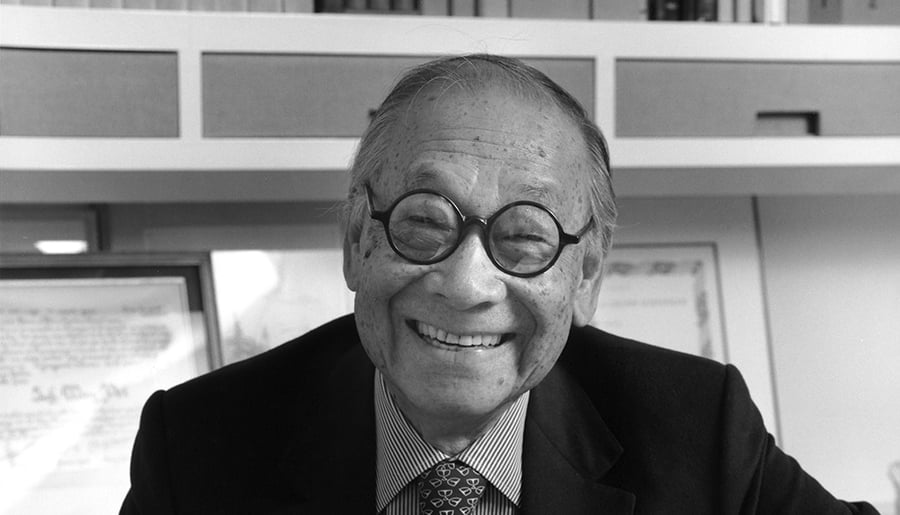

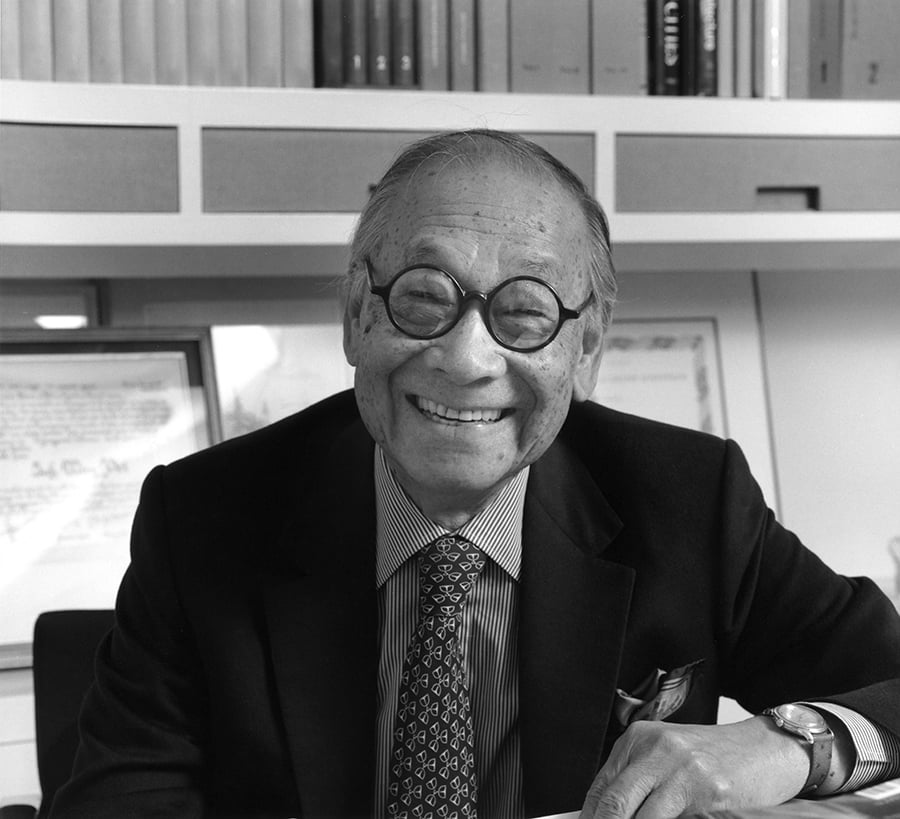

Chinese-American Architect I.M. Pei Passes Away at 102

Ieoh Ming Pei was among the world’s leading Modernist architects, designing iconic buildings throughout the second half of the 20th Century.

Today, it was confirmed by architecture critic Paul Goldberger that Ieoh Ming Pei (more commonly known by his abbreviated name, I. M. Pei) had passed away overnight.

Pei collected numerous awards over his long career, which spanned over four decades. Most recently, his centennial birthday prompted a fresh wave of retrospectives, including a symposium at the Harvard GSD and a celebration at Pei’s National Gallery of Art East Building in Washington D.C., which opened in 1978. (The building won an American Institute of Architects (AIA) Twenty-five Year Award in 2004.) Pei’s other accolades include the AIA Gold Medal (1979), the Pritzker Prize (1983), the inaugural Praemium Imperiale award (1989), the Lifetime Achievement Award from the Cooper-Hewitt, National Design Museum (2003), and the Royal Gold Medal from RIBA (2010). He was also awarded the Presidential Medal of Freedom by President George H.W. Bush in 1993.

Born in Guangzhou, China, in 1917, Pei moved with his family to Hong Kong and Shanghai during his childhood. His mother was a devout Buddhist and his father was a banker whose work put Pei in good financial stead. Neither, though, was well versed in the arts. “I have cultivated myself,” Pei once said in a lecture at the Yale School of Architecture.

At the age of 23, Pei graduated from MIT, where he became interested in the architecture of Le Corbusier and Frank Lloyd Wright. In 1938, Pei drove to Wright’s Taliesin East estate in Spring Green, Wisconsin, to meet the architect, but after two hours, Pei left empty-handed.

Pei had better luck back in Boston: The pioneers of the Bauhaus, Walter Gropius and Marcel Breuer, had fled there from Nazi Germany, taking positions at the Harvard Graduate School of Design, where Pei pursued a master’s degree. But a month into his first term, in 1942, Pei paused his studies to join the National Defense Research Committee. For two-and-a-half years he aided the committee’s research on incendiary bombs, which were being developed to target Japanese cities, especially vulnerable due to their largely wooden constructions.

Pei returned to Harvard, graduating in 1946, and quickly took up a post there, teaching alongside Gropius and Breuer. In 1948, Pei started work as an architect, practicing with Webb & Knapp, the firm of New York developer William Zeckendorf.

In just a matter of years, Pei established his own firm with colleagues Eason Leonard and Henry Cobb. His first building of note was the National Center for Atmospheric Research’s Mesa Laboratory in Boulder, Colorado, which opened in 1967. During the same period, Pei was hand-picked by Jacqueline Kennedy to design the John F. Kennedy Presidential Library and Museum in Boston. Pei would later say that the library was ”the most important commission” of his life. Mrs. Kennedy had spent months visiting with different architects, including Louis Kahn, but she favored Pei, then a relative unknown and inexperienced. “He didn’t seem to have just one way to solve a problem,” she observed. “He seemed to approach each commission thinking only of it and then develop a way to make something beautiful.” Describing her selection of Pei as a “really an emotional decision,” Kennedy noted that the architect “was so full of promise, like Jack; they were born in the same year. I decided it would be fun to take a great leap with him.”

Pei didn’t just practice in America. Work took him back to China in 1975—his first visit to his homeland since emigrating in 1934—where he lectured as part of an AIA delegation. He later designed a skyscraper for the Bank of China in Hong Kong; opened in 1990, it ranks among Pei’s most lasting and indelible projects.

Yet, Pei is bound to be remembered for his work at the Louvre in Paris. The glass-and-steel pyramid he designed at the museum’s entrance was initially snubbed by Parisians. “I received many angry glances in the streets of Paris,” he later recalled. But by the time a second, inverted pyramid, located below-grade, was completed in 1994, opinions had changed. “Looking back at it now, it all becomes rather pleasurable, because they look at me differently now,” said Pei. “That means they have accepted Le Grande Louvre.”It was a capstone to a long, productive career. By 1990, Pei retired from full-time practice and his firm, now renamed Pei Cobb Freed & Partners. The firm is still running with Henry Cobb, Michael Bischoff, Yvonne Szeto, Ian Bader, José Bruguera, and Michael Flynn as partners.

If you would like to submit a statement on the passing of I.M. Pei, please email: [email protected]

Statement from Neri&Hu:

For us, as architects trained in the U.S. and actively practicing in China, I.M. Pei’s legacy carries a meaning beyond his standing as an iconic member of the modernist generation of architects. As an Asian immigrant in the United States, who eventually established his own practice, he was a pioneer—the first Chinese-American architect to receive global recognition and create a breadth of work spanning many regions and cultures.

Although he is often described as deeply influenced by modernist icons such as Le Corbusier, Walter Gropius and Mies van der Rohe, he was intuitively guided just as much by his childhood memories of visiting Chinese gardens in Suzhou with his mother. His buildings explore the interplay between geometry and light, ancient forms and contemporary technology, spatial gestalt and structural expressionism, and most importantly for us the relationship between East and West—tradition and modernity. He managed to follow his own philosophy during an era when his predecessors and contemporaries and were focused on either breaking from history or reinterpreting history through postmodernism; Pei stayed faithful to his search for a modern language that was still contextually linked to vernacular tradition.

We admire him not just for his ability to transform simple geometries and forms into a uniquely modern language and material sensibility, but also for his unwavering advocacy for contextual development and linking design with regional influences. Our own practice at Neri&Hu shares his sentiment and view of the role of the architect as a bridge between present and past, modernity and tradition, East and West. Even as he achieved international success, upon being awarded the Pritzker Prize, his hope was to use the money to establish a scholarship fund for Chinese students to study in the U.S. This gesture reflects his commitment to mentorship and why his legacy will live on not only as an iconic modernist, but a true industry leader paving the way for the next generation of young hopeful architects.