April 3, 2019

The German Designer Who Elevated Early Modern Design in America

Kem Weber, whose work includes the Walt Disney Studios complex and numerous household and office products, fused European design concepts and American ideals of progress and industry.

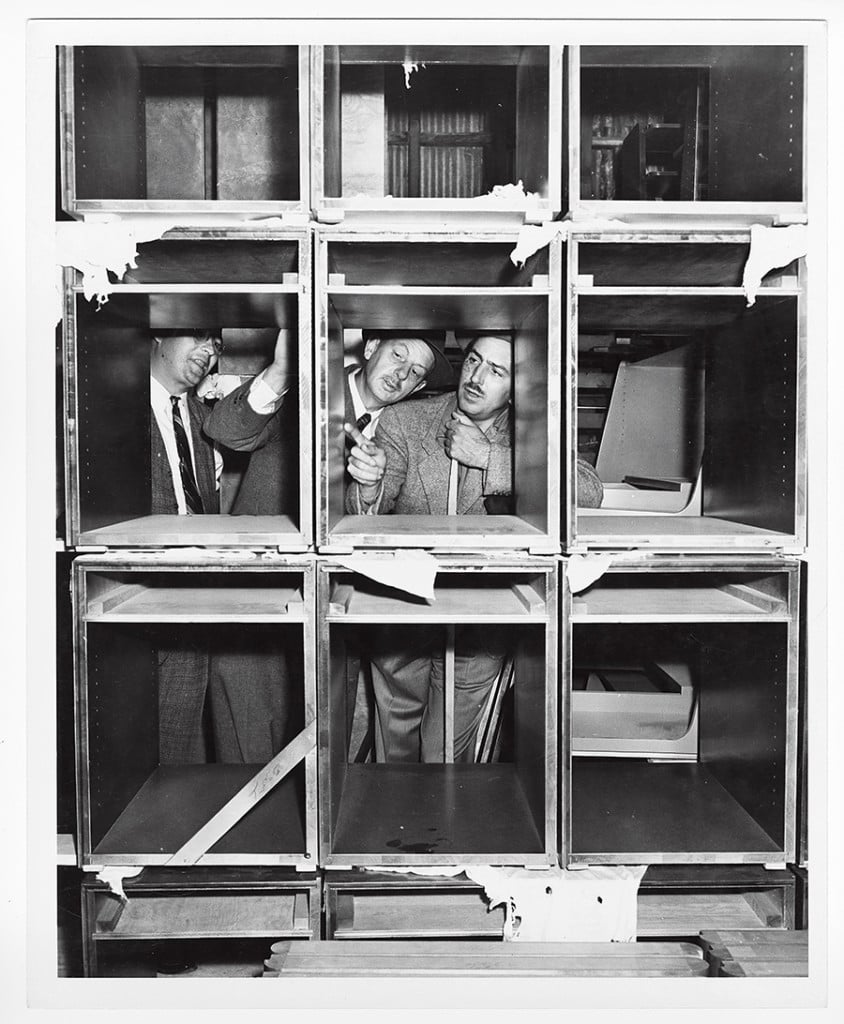

Once considered the dean of West Coast Modernism, German émigré Kem Weber helped shape 20th-century American mass society. The works that most readily come to mind include his streamlined tubular metal furniture pieces from 1928; his cantilevered Air Line armchair from 1934; and the Walt Disney Studios complex in Burbank, completed in 1939, which comprised a series of buildings and custom furnishings in colors evoking the California desert. His office equipment for Disney is still sought by collectors; Peter Blake Gallery in Laguna Beach exhibited half a dozen pieces, including an animator’s desk, at Design Miami/ last December. (All sold.)

But to call Weber a proto-Modernist doesn’t seem quite right. Rather, he was a linchpin bridging the turn-of-the-century European avant-garde and gathering Modernist currents in the United States. In his designs, one can sense competing contemporary influences forged at a time when the course of design, and modern life, was intensely contested on a global scale.

Karl Emanuel Martin Weber—he later went by Kem—was born in 1889 in Berlin to a prosperous Protestant family who owned a specialty soap company. Though he did poorly in school, Weber enjoyed crafting objects by hand, so his parents sent him to Potsdam to work in a cabinetmaker’s shop. With ambitions to become a designer, he enrolled in the Unterrichtsanstalt des Königlichen Kunstgewerbemuseums (School of the Royal Arts and Crafts Museum), which had opened in 1867 to emulate the South Kensington Museum (today the Victoria & Albert Museum in London). There, Weber studied under architect and designer Bruno Paul, eventually working in Paul’s private practice.

Weber’s association with the architect played a significant role in molding his enduring ideological positions. Paul was a founding member of the Deutscher Werkbund, formed in 1907; Josef Hoffmann, Richard Riemerschmid, and Peter Behrens were among its first members. The central controversy that animated debate at the Werkbund pitted standardization against individual artistic expression. Far from a historical footnote, this debate extended beyond Germany and persisted in America and elsewhere well into the 1930s. Designers like Weber were among the first to negotiate the forces of mass production and marketability.

In May 1914, at the height of these developments, Weber boarded an ocean liner bound for New York, before continuing on to San Francisco, where he was due to oversee an installation at the Panama- Pacific International Exposition of German exhibits he’d helped design in Paul’s office. The displays, shipped separately, never arrived. World War I had just broken out, and Weber was unable to return to Germany. Though it would not become apparent to him for some time, he would remain in the United States.

After short stints designing and selling tabletop objects and party decorations, painting billboards, teaching, and even farming, Weber moved to Santa Barbara in 1919 to set up his own arts-and-crafts studio. His works from this period bear a striking resemblance to Paul’s brand of pragmatic Modernism blended with local revivalist styles, an aesthetic to appeal to the tastes of his patrons. The historian Christopher Long noted in his 2014 monograph on Weber that the designs expressed “prewar ideas of modernism” in a postwar era.

A successful partnership with interior decorator Donna I. Youmans resulted in numerous interior commissions and caught the attention of the managers of Barker Brothers, then the largest furniture outlet in the country. (It closed in 1989.) Weber joined the company in 1921 and was soon promoted to head of the design studio. For six years he made significant contributions to the West Coast design scene, particularly with the introduction of his popular Modes and Manners retail shop, which featured gold-leaf flourishes and zigzag-patterned Art Deco walls. An article published in Good Furniture Magazine shortly after the store opened presciently noted “at some future date when the history of the American modernistic furniture movement is written, the Barker Bros. store in Los Angeles and its designer, Kem Weber, will undoubtedly be recorded as among the early leaders in its development.” His reputation soared, as did his income—he was earning an outlandish $12,500 salary (equivalent to around $180,000 today).

Weber, seeking more autonomy in his work, left Barker Brothers to open his own industrial design practice. He went on to produce designs including early streamlined works, clocks, various silver vessels, an early flat-pack system of furniture, interiors like the landmark Bixby House (1937), shop windows, restaurants, and exhibitions. That Walt Disney personally hired Weber to design his animation studios says something about the impact Weber exerted in his own lifetime.

The range of these projects reveals Weber’s willingness to adapt to the needs of the time. Speaking at the 1928 Macy’s International Exposition of Art in Industry, for which he had designed a three-room apartment to great fanfare, Weber described the role of the designer as “one who can absorb national occurrences and express them appropriately in form and color. This is the age of skyscrapers, subways, and telephones; the modern designer expresses the spirit of this age.”

Propelled by personal ambition, yet chastened by economic realities and unforeseen setbacks, Weber accomplished what many of his peers couldn’t—putting his Modern designs into mass production. His career as an industrial designer and architect, launched in Berlin in 1907 and ending with his death in Ojai, California, in 1963, spanned an era of continual and rapid stylistic, social, and economic shifts that he was able to adapt to through his designs. That stands as Kem Weber’s most crucial contribution to the nation’s design treasury.

You may also enjoy “Furniture Studio SIOSI Crafts Unique Furniture Pieces in a Danish Modern Idiom.”

Would you like to comment on this article? Send your thoughts to: [email protected]