September 25, 2019

Behind the Curtain: How Marybeth Shaw Drives Creative Production at Wolf-Gordon

For decades, Shaw has looked to unconventional talents, collaborating with fledgeling designers to bring their textile work into production.

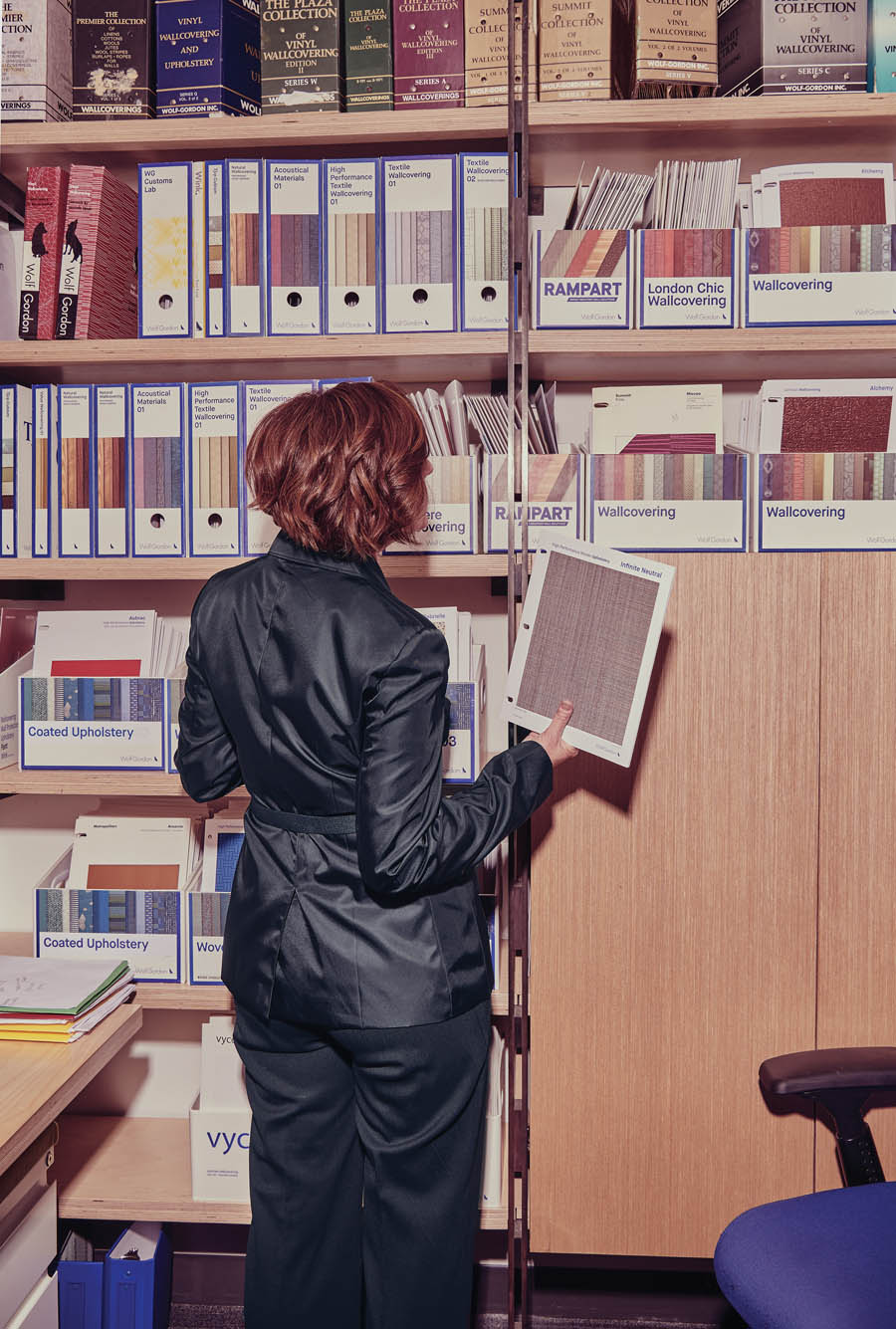

“I don’t like ‘stuff,’” proclaims Marybeth Shaw, the chief creative officer, design and marketing, of the American interior finishings company Wolf-Gordon. Her austere office in its Manhattan headquarters corroborates Shaw’s disdain for needless clutter; it’s architect-tidy, with books and effects concealed behind cabinets, and nary a stray sheet of paper atop her white desk. As the driving force behind Wolf-Gordon’s upholstery, drapery, and wallcovering products, she has made it her mission to deliver products that transcend “stuff” and exemplify her notion of “good design.”

Shaw oversees a studio of young designers who generate Wolf-Gordon’s in-house collections, developed largely to serve the contract, hospitality, and health-care markets. Since 2001, she has also been augmenting these standard lines with licensed textile collections by invited collaborators, bringing a global perspective to Wolf-Gordon’s catalog. For Shaw, these commissions provide an opportunity to look at the bigger picture— to push design into new territory by thinking beyond market conventions to ask instead, “What does the world need? What does our soul need?”

Shaw has been with Wolf-Gordon for 15 of the 52 years it’s been in operation, first as its creative director from 1997 to 2003, and in her current role since 2011. Sandwiched between was a seven-year stint running Shaw Jelveh Design, a full-service, Baltimore-based studio she founded with her husband, an architect. (Shaw holds a graduate degree in city planning from MIT and studied architecture at the École d’Architecture de Paris-Belleville.) It was in the early 2000s, during her first tenure at Wolf-Gordon, that she pioneered its licensed partnerships, spicing up the brand’s wallcovering lineup with bold geometry and digitally generated patterns by blue-chip designers like Laurinda Spear and Karim Rashid. The collections drew notice and signaled Wolf-Gordon’s willingness to offer designers patterns that pop off the wall, rather than blend into it.

Upon her return to the company, Shaw got a new title and was charged with a new mandate: elevating the brand’s creative profile and leading its foray into the contract textiles category. Inspired by the opportunity to distinguish Wolf-Gordon’s brand, Shaw embraced the idea of working with emerging designers unfamiliar to the U.S. market.

During her intervening years at Shaw Jelveh, Shaw reflects, she “learned a lot about working with younger designers and developing them, and also [how to] conceptualize myself.” She returned to Wolf-Gordon “with a lot more experience and confidence to go out and look at [collaborators] who are not already big stars.” To date, she has developed 13 licensed textile collections, all with European designers virtually unknown in North America previously. Recent collaborations with young Dutch designers Mae Engelgeer and Aliki van der Kruijs have won awards at NeoCon and NYCxDESIGN, helping position Wolf-Gordon as a forward-looking brand with a finger on the pulse of design.

Where does Shaw look to discover new talent? In an era when the internet is a showcase for design’s rising stars and Instagram dictates popular taste, she prefers to take a more hands-on approach. At design fairs, Shaw makes a point of perusing student work and visiting the booths of early-career practitioners. “I’m seeing whose work might be exciting, and what’s a fresh voice that I could bring over to our brand and to American interior designers,” she says. “I don’t go on social media and start looking at how many followers they have.” Increasingly, ambitious designers are contacting her, Shaw finds, enticed by the prospect of working with a company of Wolf-Gordon’s size and reputation.

With each new collaborator, the design process begins with a strong concept that unites every textile in the collection—a foundational element Shaw refuses to rush or constrain. “There’s something about how seriously design is developed in Europe that I’m still very attracted to,” she admits, recalling her architectural training in Paris, where students were given ample time to explore and refine their ideas. The concept development stage can take as little as three months, or it can draw out over several years as ideas, experiences, and points of inspiration cohere. Shaw lets the designer’s imagination roam unfettered during this process, to arrive at something that’s truly unique. “We want the designer to go out on a limb and really push the collection forward aesthetically; we don’t want to create limitations,” she says.

As the initial designs develop, Shaw teases out patterns and colorways that make a well-rounded, commercially viable collection. She’s looking for modern classics—those textiles that can work in both corporate boardrooms and boutique hotels—as well as more quirky statement pieces with large-scale patterns and edgy colors that express a collection’s point of view. “We’ll see items that are no-brainers,” Shaw says, referring to the textural solids, the stripes, and other traditional bases she needs to cover. “And then there’ll be something that’s a little more challenging, but significant for that collection, for that designer’s voice.” She might steer palettes or patterns in a direction more suitable for Wolf-Gordon’s clientele, because “we want the designer to benefit from their relationship with us,” Shaw is quick to point out. “We want the collection to sell, and we want them to get their royalties.”

This kind of collaborative engagement with diverse voices and ideas shows the industry that “Wolf-Gordon is participating in the design continuum, not just giving [designers] something they already know they want, but giving them something they didn’t know they wanted,” Shaw says. “I think that’s our responsibility as a design company.”

You may also enjoy “In London, a Researcher Guides Biodesign into Uncharted—and Newly Relevant—Territory.”

Would you like to comment on this article? Send your thoughts to: [email protected]

Recent Profiles

Profiles

Democracy Needs Room to Breathe