January 17, 2017

These Mexico City Developers Preserve Landmarks & Battle Gentrification

This developer is bringing new life to Mexico City’s historic neighborhoods—but keeping focus on equitable, sustainable growth.

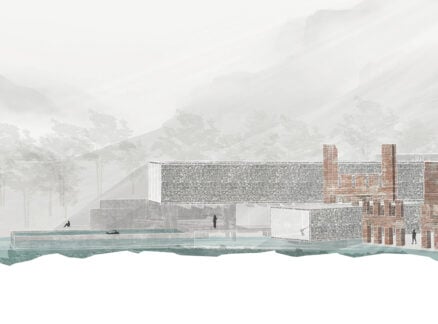

CH-Reurbano, in Mexico City’s Roma Norte neighborhood, is an adaptive reuse of a historic mansion by developer ReUrbano and architecture firm Cadaval & Solà-Morales. The mixed-use redevelopment, which was completed last year, includes an additional contemporary floor of residences that are not visible from the street.

Courtesy Sandra Perezneito

Walking through the neighborhoods at the heart of Mexico City, you’d never suspect that the area had been decimated by an earthquake on September 19, 1985. Thousands of people died that morning, and almost half of the 500 buildings that collapsed were in the city’s core, between Zócalo square and Chapultepec park. The rich and educated fled to the suburbs, returning only in recent years as Mexico City’s downtown made a comeback. In Centro, the historic district, trolleybuses ply the narrow streets and businesses thrive, thanks mainly to the munificence of billionaire business magnate Carlos Slim Helú. To the southwest of this district, art galleries and cafés have taken over and gentrified La Roma (earning it the nickname of Williamsburg South, in a nod to the Brooklyn neighborhood).

But neither philanthropy nor hipsterization is a particularly groundbreaking method of urban revival. It is in Juárez, a formerly gracious but now shabby residential neighborhood, that a series of award-winning buildings is showing the way forward to a visionary, people-centered urbanism. And behind these mixed-use, bike-friendly structures is a rm of architecture-trained developers called ReUrbano.

“My father was born and raised here,” says Alberto Kritzler, one of the founders of ReUrbano. “It’s a neighborhood that I’ve known since I was a kid. I used to come here pretty much every weekend, to stay with one set of grandparents or the other.” When the slow revival of the downtown area began, he and cofounder Rodrigo Rivero Borrell were among those who considered moving back from the suburbs where their families had ended up. Kritzler, an engineer, and Rivero Borrell, an architect, were working on projects in Polanco and La Roma when they discovered that they shared the same broader vision for Mexico City and its historic core—one rooted in adaptive reuse.

An image of the interior of Milan 44, a mixed-use space in the Juarez neighbored developed by ReUrbano and designed by Francisco Pardo. On the wall it reads, “A place for everything. A place for everyone.”

Courtesy Sandra Pereznieto

“We were hoping to build a quality of life,” Kritzler says. In 2010 the duo invested in their first building, a modest structure in Juárez that was designed by noted architect Juan Segura Gutiérrez in the 1930s, but had fallen on hard times. They decided to restore the property themselves and, in the process, defined the broad elements of the ReUrbano approach.

The first comes out of their love of history. “One of the main ideas was that we had to invest in or look for landmarks,” Kritzler says. ReUrbano’s real estate guide is a 1920s map of Mexico City, because Rivero Borrell and Kritzler have a penchant for mansions that are about a century old. It’s easy to see the attraction of those heady times—Porfirio Díaz’s three-plus decades as president between 1876 and 1911 saw an extraordinary surge in construction in the city, and despite the revolution that followed, it continued to grow rapidly. “Mexican architecture of that era is very, very strong,” Rivero Borrell says. “Lots of architects were relevant to cultural movements in the early 1900s.” The flight of the original inhabitants left many of these buildings in a neglected or abandoned state, so a discerning developer could find architectural gems at a bargain price.

The second element is a kind of curatorship. After finding historic buildings with potential, ReUrbano identifies the right architect to carry out the process of adaptive reuse. “They are working with the most talented architects in the city, and I’m not talking about me,” says architect Eduardo Cadaval, whose Barcelona- and Mexico City–based practice, Cadaval & Solà-Morales, has completed two buildings with ReUrbano, with a third under construction. Cadaval went to school with Rivero Borrell, so he doesn’t count his firm among the emerging architectural practices, such as AT103 and La Metropolitana, that ReUrbano has brought to the fore.“ In many cases, the work that these offices have been doing with ReUrbano is among the greatest examples of their work,” he says.

Photography courtesy Sandra Pereznieto

ReUrbano’s projects are mixed-use redevelopments because it firmly believes that is the way to diverse, safe neighborhoods. “The authorities should take a stronger position to help the city’s diversity,” Kritzler says, “to have mixed socioeconomic levels and ages— older people and kids.”

Courtesy Reurbano

Then comes the process of breathing new life into the historic properties. ReUrbano and the architects work closely with Mexico City’s agency for preservation and conservancy. “In both our projects, we saved 90 percent of the building,” Cadaval says. At Cordoba-Reurbano, a building that won the 2016 FAD prize in Spain as well as a silver medal at the Mexican Architecture Biennale, Cadaval’s firm put a tasteful black stainless steel addition atop a residential building to create nine housing units with commercial spaces at street level. At CH-Reurbano, the architects added concrete reinforcement to a sinking building, shoring it up for a development that includes commercial spaces at street level, offices on the second floor, and residential units on the floors above.

This kind of mixed-use programming is a firm tenet at ReUrbano, a way of creating the diversity and energy that these neighborhoods lacked even when they were first built as citadels for the rich. “This might sound normal in many other cities in the world,” Cadaval says, “but Mexico City is ruled by zoning that assigns unique uses to most buildings.” ReUrbano’s way out is to leverage the buildings’ checkered past—which invariably involves commercial tenants at some point—as the basis for mixed-use rezoning.

A transformative moment in Rivero Borrell’s life provided the final element of the ReUrbano formula. “One day, 12 years ago, I had to bike to work because Paseo de la Reforma [a main artery in the city] was blocked because of political demonstrations,” he says. “My quality of life changed dramatically.” So from the very first development, the only parking space that ReUrbano has provided in its buildings has been for bikes—no one who lives or works in the buildings drives a car. This seems a radical move, given the stereotype of Mexico City’s car-choked streets, but Rivero Borrell questions that perception as a bit elitist. “We’re used to sharing stories but not sharing facts,” he says. “Only 18 percent of the population moves around in cars.”

Transit choices are one of the ways that ReUrbano buildings connect with the larger urban scale. By acquiring multiple buildings in one area, as it has done on Havre Street in Juárez, the firm has found that it can start making a real difference. “It’s very interesting to see how the community began to interact with each other,” Kritzler says. “Neighbors started painting their facades, a pizza place opened across the street, the guy who sold newspapers on the corner is now repairing bicycles.” There is change, but importantly, it is as nonelitist as Rivero Borrell and Kritzler can make it. “Working with someone who has that vision is just amazing,” Cadaval says. “ReUrbano is a very active part of the transformation of this area.”

In our inequitable cities, however, talk of urban revival is inseparable from the mechanism of gentrification—as building stock improves, real estate values go up, and neighborhoods become defined by income level. Kritzler offers some nuance on ReUrbano’s situation: “Most of the people in this part of the city are owners of the buildings. That changes, of course, the topic of gentrification.” But he and Rivero Borrell don’t shy away from their responsibility in the matter. They work hard to see that long-time business owners or inhabitants aren’t squeezed out, by demarcating subsidized commercial spaces and even, in some cases, offering to design those spaces. “We’re actually putting a lot of time into doing analysis and research into gentrification,” Kritzler says. “We still feel that our best way to contribute is by pushing the authorities to move forward with intelligent housing projects and buildings. The city has amazing public spaces, and we have to get involved in reactivating those spaces as well.”

ReUrbano’s latest building on Havre Street is Havre 77, which is now also home to the firm’s offices. The building was designed by Julio Amezcua and Francisco Pardo of AT103, and includes a contemporary “prosthesis” that envelops a historic home. Bold colors and material choices help bridge the old and new sections while also providing opportunities for wayfinding.

AT103’s addition to Havre 77 made it possible to have sunlit homes (above), as well as flexible, multifloor spaces occupied by companies like Kickstarter (below).

In keeping with ReUrbano’s mixed-use philosophy, the firm invited noted chef Eduardo Garcia to open the Havre 77 restaurant at street level in the old structure. With interiors by San Francisco– based designer Charles de Lisle, it has become one of the area’s most acclaimed eateries.