January 19, 2016

Remembering Richard Sapper, 1932–2015

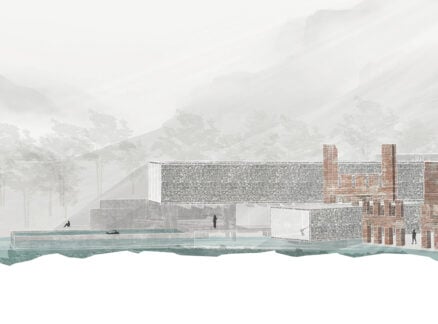

A technical genius, a generous collaborator, and an adventurous man—Sapper was all these things, say his former friends, associates, and admirers.

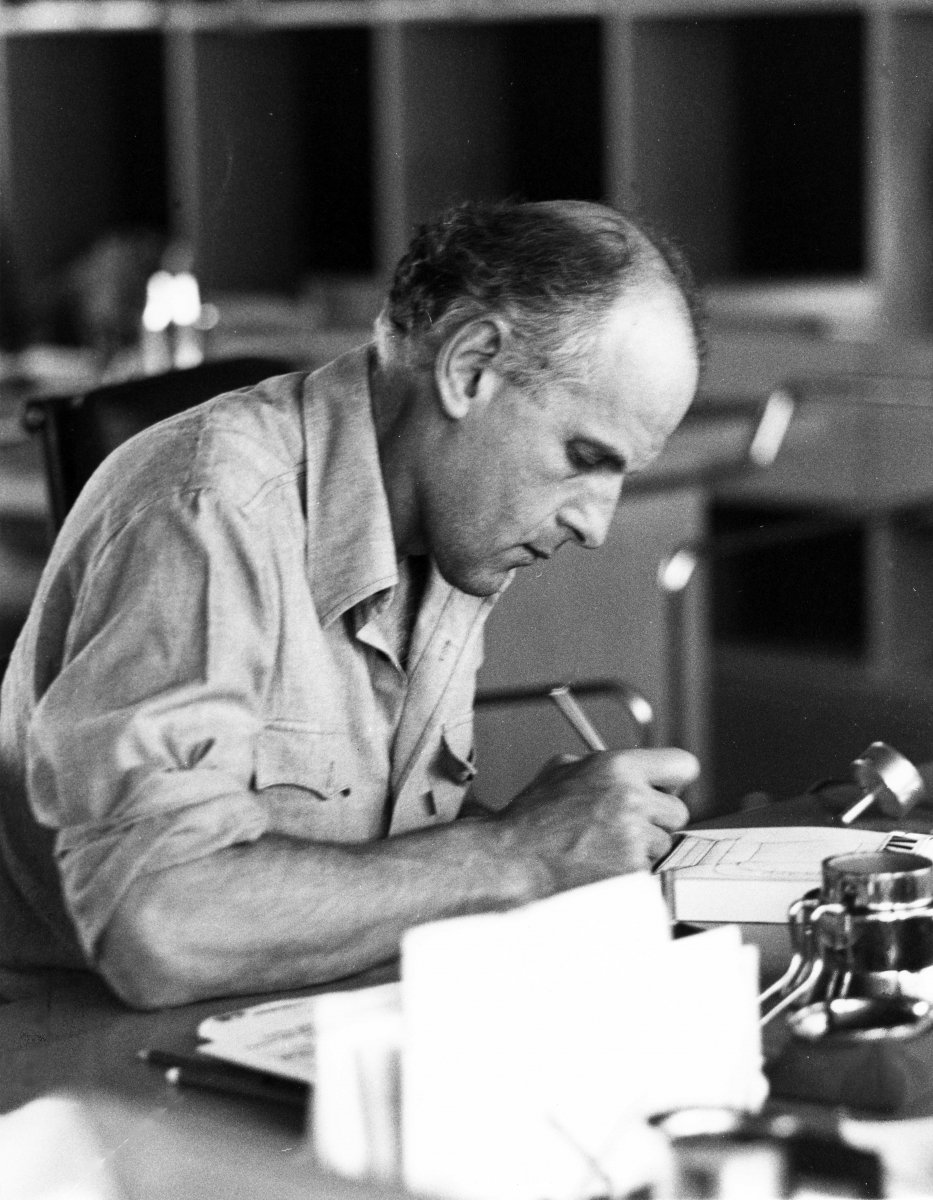

Richard Sapper, 46, at work in his office in 1978

Courtesy Richard Sapper Design

Close associates, manufacturers, and contemporary designers reflect on the great Modernist industrial designer, who passed away on New Year’s Eve in Milan.

An Adventurous Life

In recent years, as Richard and I collaborated on a definitive study of his work, an intimate friendship developed, and I came to understand his approach, his techniques, and his motives.

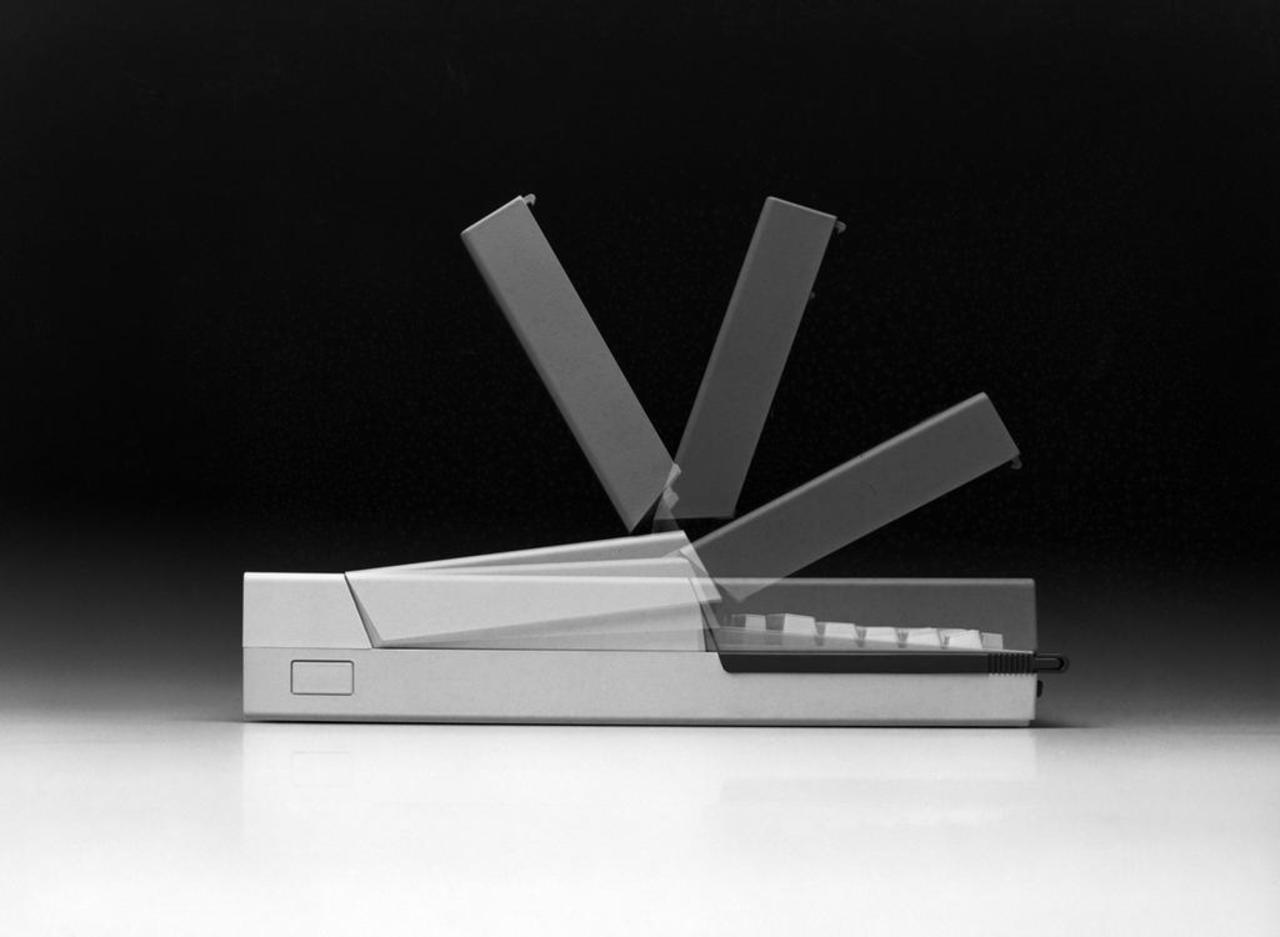

From a pen to a bus, Richard was comfortable working in all scales, and he was able to design successful products for large corporations and small family owned businesses alike. His business acumen and understanding of the function of beauty gave him sway over industry in a way that few designers of his generation had, and as a result he was able to assert his subjective thinking over design at a mass scale. He would refer to the all-important “kiss from the muse” that was necessary to begin each project, and his poetic approach favored an element of surprise. His water kettle for Alessi held a prize for the user who would clean it, as its polished surface reflects the world around it, and his ThinkPad laptop conceals its keyboard and digital content inside a simple black box. While his designs were often radical and technological, he was concerned with participating in an ancient legacy of form and drew much of his inspiration from premodern designs. He was an avid skier, windsurfer, sailor, rally racer, even wind glider, and his love of motion (and forms in motion) translated into many kinetic designs such as the Tizio lamp and the Sapper monitor arms.

The Tizio desk lamp designed for Artemide in 1972

Courtesy Richard Sapper Design

Richard always spoke fondly of his early mentor, the theologian and cultural critic Romano Guardini, and his longtime collaborator Marco Zanuso. For decades he worked closely with the model maker Giovanni Sacchi and the photographer Aldo Ballo, who respectively helped craft and communicate his work. Later in life, as he was increasingly on the road, he was known to improvise models for clients, like a computer model that he made on short notice at a friend’s violin repair shop in New England. He was also unique in that he always chose to work from his home offices, in Milan, on Lake Como, and in Los Angeles, and kept a small roster of assistants, many of whom worked from their own homes or studios. He was known to host meetings with his clients, particularly IBM, on the lawn of his home in Como, where it was common to pause a meeting for a jump in the lake. For Richard, life and work were one and the same.

Many journalists have written about how he didn’t like to talk about his work, preferring to allow his designs to speak for themselves. While this is true, Richard loved a good conversation with friends, especially one fueled by “fire water,” Cynar or Punt e Mes, which Richard liked to serve on ice. Richard thought design should address posterity, and in the days after he passed away it occurred to me that his personality, his love of adventure and surprise, his warmth, and his special blend of engineering and humor survive in his products.

—Jonathan Olivares, designer and editor of Richard Sapper (Phaidon, 2016)

The Mod 5140 personal computer designed for IBM in 1986. Sapper later designed the ThinkPad laptop for the computing giant.

Courtesy Richard Sapper Design

Technical Genius

It’s no small feat that many of Richard Sapper’s iconic designs became instant objects of desire. My favorite is his Tizio table lamp for Artemide. Its elegant, crane-like structure swivels and adjusts like a marionette, but its real breakthrough is the ingenious technology. Gone are unsightly cords and wires: The electric current that travels through the aluminum arms to illuminate the tiny halogen bulb was the seed that spawned subsequent suspended cable light fixtures.

—Cara McCarty, Curatorial Director, Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum

Sense of Wonder

Richard Sapper’s Tizio lamp for Artemide sits perfectly on a midcentury-modern walnut-and-glass side table in the living room of my family’s cottage in the Hamptons. Each time I visit, I find myself tinkering with the lamp’s movements like a child in wonder. Sapper’s work is a paradox. At once it is highly rational, visually effortless, yet functionally complex. His influence on design will not fade anytime soon.

—Brad Ascalon, designer

The TS 502 radio designed with Marco Zanuso for Brionvega in 1963

Courtesy Richard Sapper Design/Photograph by Serge Libiszewski

Wide Influence

He was a giant of industrial design, and we collected his work for the Stewart Collection in Montreal—from the iconic Tizio lamp to his extraordinary work in partnership with Marco Zanuso. Those radios and televisions for Brionvega are unsurpassed in their exquisite beauty. I always admired his international presence in the design world—in Italy and Germany— but also his teaching in the United States and England as well as Germany. He lived the ideal of design as an international phenomenon.

—David Hanks, Curator, Stewart Program for Modern Design

The Sapper monitor arm designed for Knoll in 2012

Courtesy Knoll

Generous Collaborator

It’s a big personal loss, because in addition to being a great designer, he was a mentor for me in many ways. He’s the link that goes back in Modernism to people like Marco Zanuso, which takes you back to Gio Ponti. We’re losing that link now, and I consider myself extremely privileged to have worked with him for the past ten years.

The product that he worked on for Knoll is a series of supports for technology, and every single one of the people at Knoll that worked with Richard wrote to me and told me that he was one of the most important people they have worked with in their time frame here.

I last saw Richard in the second week of December, in the hospital. We were discussing another project, exchanging drawings and information. It was a wonderful meeting, and we sat for about three hours until the nurse threw me out. We got a lot of work done, because being in the hospital, he was completely bored. He was in very good spirits when I saw him, and very inquisitive, and very excited to be working on something.

Richard was a very special guy. He affected me and the people I work with in his professionalism. But maybe much more important than that, he affected millions of people by the objects that he designed. He made things that made people happy and were useful to them. That’s incredible.

—Benjamin Pardo, director of design, Knoll

Products that Sapper designed for Alessi include the 9091 kettle with a melodic whistle from 1983

Courtesy Richard Sapper Design/Photograph by Aldo Ballo

Hint of Transcendence

Tempus fugit. Another of my maestros leaves. Together with Ettore Sottsass, Achille Castiglioni, and Alessandro Mendini, Richard Sapper had been for me during the ’70s a beloved master, unequalled for his surgical precision in translating the presence of his imagination into real industrial products that are close to perfection.

I worked with Richard for almost 40 years, since I asked him to design the first Alessi espresso maker, the 9090, which has been in the catalog since 1979 and won the XI Compasso d’oro prize. He created some of the most iconic and timeless products for us, but he did much more: he contributed to the building of the Alessi identity as an Italian design factory by helping us understand with his projects and his design practice that industrial products may not be just “merchandise”—they can have a “soul,” a hint of transcendence.

Besides the 9090 espresso coffeemaker, some of his projects for us include: the kettle with melodic whistle (1983), the pots-and-pans collection La Cintura di Orione (1986), the tea and coffeepots for catering 4060 (1982), the watch Uri-uri (1988), the teapot Bandung (1992), the stackable trays RS02 (1995), the electric coffeemaker Cobàn (1997), the cheese grater Todo (2004).

“My thinking process usually starts from a thing that I feel does not exist,” Sapper used to say. He was used to working on only a few projects at the same time, and only those that really interested him—like all good designers should.

—Alberto Alessi, president of Alessi S.p.A. and head of marketing strategy, communications, and design management

Pleasure Principle

When I’m home, the first object I use every day is Richard Sapper’s stovetop espresso maker. I remember wondering about the handle when it was brand-new—why brown? Not long after, as the pot began to take on the patina of use, the color achieved a playful intelligence: It matches the coffee stains perfectly. And it’s a pleasure to use, even half asleep. As my mental checklist for the day begins to take shape, the espresso starts to hiss and sputter, filling my kitchen with a delicious smell. Thank you, Mr. Sapper.

—Leon Ransmeier, designer

The 9090, Alessi’s first espresso maker, designed in 1978

Courtesy Alessi

The Minitimer kitchen timer from 1971

Courtesy Richard Sapper Design

The Algol portable television developed for Brionvega in 1985

Courtesy Richard Sapper Design/Photograph by Aldo Ballo

The Sapper Executive Chair for Knoll

Courtesy Richard Sapper Design/Photograph by Aldo Ballo

The Zoombike folding bicycle produced by Elettromontaggi in 2000

Courtesy Richard Sapper Design/Photography by Luciano Soave

The Grillo Telephone for Siemens Italtel, 1965

Courtesy Richard Sapper Design/Photograph by Roberto Zabban