September 16, 2015

Sara Little Turnbull, Corporate America’s Secret Weapon

For more than five decades Sara Little Turnbull has been corporate America’s secret weapon, working behind the scenes, operating at the intersection of design and commerce.

Over her 83 years, Sara Little Turnbull has amassed a diversity of knowledge by reading five newspapers daily and nearly 60 publications a month, but mostly she relies on firsthand experience.

Courtesy Joe Budd

Sara Little Turnbull, pathbreaking product designer, has died at the age of 97. In November 2000, Metropolis profiled Turnbull at length, introducing to a younger generation the work of the designer and culture anthopologist. Her career spanned decades, from her time at House Beautiful in the 1940s–50s to her later consultation work for major corporations, such as Coca-Cola and 3M, and government agencies like NASA. We republish the story below.

Sara Little Turnbull is a designer, strategic planner, teacher, cultural anthropologist, problem solver—and master of the “creative accident.” A woman of formidable intellectual stature, she sizes you up from the height of her diminutive four-foot, eleven-inch frame. Within minutes of meeting her, your perspective on the world changes to adjust to hers. Feeling like Alice in Wonderland—a little too tall suddenly—you’re quite willing to squeeze into rabbit holes to follow her nimble mind wherever it wants to go.

To explain what she does—and why it’s relevant to our culture now—Turnbull must first debunk some of the current assumptions about design and its function. In the process she is likely to tell you how she came up with the concept for a new baking-dish lid after observing in Kenya the way cheetahs use their paws to capture and hold their prey; or how she got the idea for a line of energizing bath towels from watching traditional weavers in Malaysia; or how, to design a burglar-proof lock, she first interviewed thieves behind bars—the real security experts.

For more than five decades now, Mrs. Turnbull, née Sara Little, has been corporate America’s secret weapon. Working behind the scenes with top product-development people at General Mills, Corning, Procter & Gamble, and 3M—to name just a few of her long-term clients—she operates at the intersection of design and commerce. An independent thinker, she is a role model for many women. Los Angeles interior designer Gere Kavanaugh believes that Turnbull paved the way “for the next three or four generations of female designers.” To Turnbull, though, this is not a compliment. “I am not a female designer!” she says. “I am just a designer.” Married late, at age 48, to forest-product-industry executive James R. Turnbull, she was a modern woman before her time. One of Turnbull’s former students, Jennifer Ayer Sandell considers her a mentor. “She is an informal adviser to me and to a lot of my girlfriends in the corporate world,” Sandell says.

If she is so popular, why isn’t Sara Little Turnbull a household name today? The reason is simple: almost no one can explain exactly what it is she does. When she was a consultant at Revlon—a stint that lasted almost 20 years—someone once asked then-president Charles Revson to explain Sara Little’s contribution to his company. “After all these years,” he answered, “I don’t understand a thing she says—but I can’t live without her!”

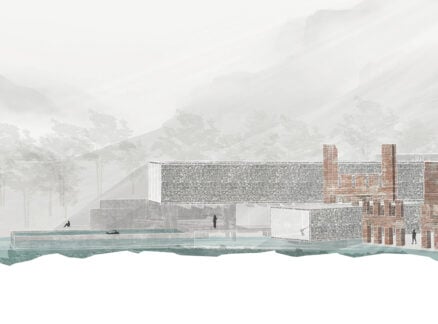

Turnbull is now on the faculty at Stanford University Graduate School of Business, as director of the Process of Change Laboratory. She is also a consulting professor at the School of Engineering, as part of the Integrated Design for Marketing and Manufacturing program. In this academic context she explores with students “how a deeper understanding of culture can be a competitive advantage in business.” The Turnbull approach is interdisciplinary—the teaming of business and engineering students is mandatory for the Integrated Design course, an intensive 21-week program. Forty students, divided into ten teams of two MBAs and two engineering graduate students, compete to design, manufacture, and market the same working consumer product prototype—a citrus juicer one year, a compact bike pump the next.

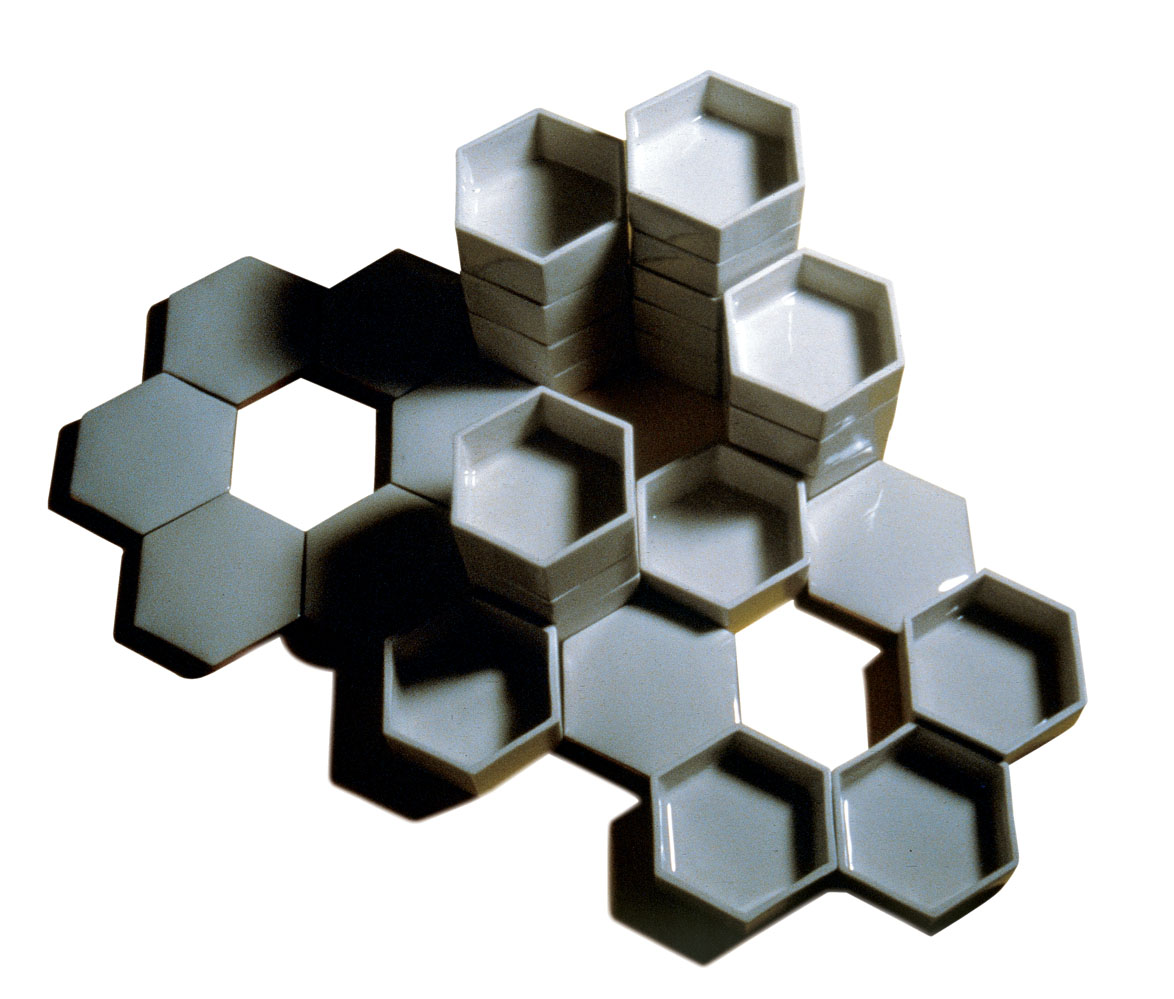

Turnbull draws on her immense collection of artifacts for inspiration. In 1976 she used modular Japanese boxes, meant for pickled vegetables, to illustrate city planning methods to the Ministry of Housing in Malaysia.

Courtesy Larry Bullis for Sara Little Center for Design Research/Tacoma Art Museum

“I see design as essentially creating order,” Turnbull says, “but I also encourage students to learn from their own experience, at times letting their minds meander to discover the unexpected and the creative accident.” What she calls the Process of Change is a dynamic methodology she developed during years exploring creative opportunities at the corporate level—a technique that’s part logic, part chutzpah.

Born in Manhattan in 1917 and raised in Brooklyn, Turnbull grew up in a modest Jewish household. Her mother came from a family of Hebrew scholars and instilled in Turnbull an intellectual curiosity for all things big and small. To this day she credits her mother for teaching her to appreciate design. Turnbull remembers fondly her mom displaying the meager yet precious provisions for the day—an eggplant, a bunch of scallions, a cucumber, an onion—then describing each in detail, from the rotund fleshiness of the eggplant to the gossamer layers of the onion, reluctant to reveal its succulent center.

Turnbull attended Parsons School of Design in the late 1930s. By 1941 she was an editorial assistant at House Beautiful, where she quickly rose to the position of decorating editor. Already she showed an uncanny ability for anticipating the next cultural trend. Even before the end of World War II, she was developing for the magazine a series of articles addressing the new realities of what she predicted would soon be the postwar boom. Under a “Girl with a Future” seal-of-approval logo, she introduced readers to modern ideas such as sharing an apartment with a roommate, decorating a home for a returning soldier, doing away with the cleaning lady, or making the best of the GI Bill.

At the time she lived in a room at the Lombardi Hotel in Manhattan, artfully turning a couple hundred square feet of convenient real estate into a model of urbane efficiency, thanks to tucked-in storage spaces, folding screens, and collapsible furniture. When her sister was diagnosed with cancer in the late 1940s, and staggering medical bills had to be paid, she turned her room into a tiny design office. In addition to her day job, she began to design packaging for Macy’s private-brand products. Soon other clients were clamoring for her services, among them Elizabeth Arden and Lever Brothers. Not knowing how much to charge, she decided one day to add the doctor, hospital, surgery, and nursing expenses together and make that her fee. To her surprise, the clients didn’t balk.

Objects from Turnbull’s collection. Left: A cigar mold. Right: A mold for embossing leaves and petals onto silk, circa 1940

Courtesy Larry Bullis for Sara Little Center for Design Research/Tacoma Art Museum

From then on her freelance practice flourished, as did the quality of her clients. “I quickly became one of the highest-paid designers in the business,” she says. “I would never have been as successful—would never have done as much as I did—if I hadn’t been forced by circumstances. And you know what? I got paid, and then I got paid, and then I got paid.” By the time her sister died in 1954, Turnbull had grown into a savvy design professional who was not intimidated by powerful corporate clients. In 1958 she quit her job at House Beautiful and officially became Sara Little, Design Consultant. She was 41, single, and well-to-do.

The country was ready for its second postwar boom. Many of the patents for advanced technologies granted during the war were on the verge of expiring. In the United States patents are given for a limited time—17 years—and unless they are used commercially within this period, they fall into the public domain. By 1958 companies like 3M and Corning were in danger of losing ownership of some potentially valuable wartime inventions—unless they created new products with them. They began to scramble for ideas. Many of the novelties introduced in the 1960s, such as Tang and Spandex, came about as a result of this second wave of urgent postwar inventiveness.

Around the same time Turnbull wrote an article in a trade publication titled “When Will the Consumer Become Your Customer?” In it she discussed the fact that most companies at the time created products for retailers—not for the people who were actually going to use them. This was the only article she ever wrote—Turnbull doesn’t waste time on paper trails, writing only two memos during her career as a designer—but it had a tremendous impact on her life. The head of Corning’s consumer products division and a senior vice president of 3M, who both had read her article, called and asked her to talk to them. “I came away with a practice that sustained me for 35 years,” she says. Indeed, brainstorming with heads of companies really is her thing. As design consultant Ellen Newman, daughter of the late Cyril Magnin and a friend of Turnbull’s for 50 years, explains: “CEOs in this country just want to talk to Sara. She’s one of the few designers who do not intimidate them.” To this day top decision makers still call on her when they need to stretch their minds or discover new opportunities for their industries, from reinventing the way we store food in a refrigerator to making the changing of lipstick colors less arbitrary.

“I am a young oldie,” she explains. “There are many young oldies like me out there, and society today is somewhat more receptive to us—as long as we are willing to keep learning new things all the time.”

Corning and 3M have been faithful clients, along with Coca-Cola, Ford Motor, Scott Paper, American Can, Neiman Marcus, Revlon, DuPont, Pfizer, Nissan, and others. But Turnbull will not share with anyone the specifics of her contributions to the numerous projects to which she has been privy. In fact she becomes very unhappy if you try to find out exactly what she discusses with clients behind closed doors. “I am scrupulous about not taking credit for any idea,” she insists. “An original concept may be mine, but the result is only as good as its final implementation.”

For Turnbull, staying plugged in at age 83 is a discipline. “I am a young oldie,” she explains. “There are many young oldies like me out there, and society today is somewhat more receptive to us—as long as we are willing to keep learning new things all the time.” Her insights are not the product of serendipitous flashes of brilliance, but of sustained efforts to keep up with the culture. Turnbull reads—and clips—five newspapers daily: The Wall Street Journal, The New York Times, The Japan Times, The China Strait Times, and The London Financial Times, which she thinks is the best paper of all. She also reads about 60 publications a month—everything from scientific journals to consumer publications, trade press, and magazines. She has archived all of her clippings since the early 1960s; they are the backbone of her “lab” at Stanford.

“Everything that’s in my head is in these drawers,” Turnbull says, pointing at the file cabinets that surround the Process of Change laboratory conference room. “I have not allowed this information to be put on an electronic database, because that’s not what I think this material is.” Students and clients come to study her files right here, with her. Neatly classified in bright red folders and constantly updated, the information reflects major trends in design. There are more than 375 categories, but no fancy cross-referencing. More than a systematic research tool, the materials are there to stimulate thinking by providing an interdisciplinary overview from a global cultural perspective. “Sure, you can go online and get bits and pieces of information instantly,” Turnbull explains. “In less than 25 minutes on the Internet you can sift through material that takes me five hours to read. But I don’t think you know the same thing when it’s over.”

To explain how her mind works, she tells the story of how years ago she solved a problem for “an international client in the food industry.” One of their most popular cake-mix products wasn’t selling in England. They dispatched her to London to find out why. Turnbull stayed at Claridge’s Hotel, doing intensive research—as she always does—frantically interviewing everyone from psychologists to pastry chefs. After ten days, she had not come up with much and had to admit that she had failed her mission. She packed her bags and booked herself on the next flight to New York. With an hour to kill before going to the airport, she decided to have a proper English high tea, something she hadn’t had time to do while at Claridge’s. Ordering pastries instead of the traditional cucumber sandwiches, Turnbull was surprised to be served a plate of tiny cakes—but no fork with which to eat them. Just as she was about to summon the waiter, an alarm went off in her head. “I suddenly realized that I had to take this incident seriously,” she recalls. “The moist-looking cakes were of a completely different texture from what I expected. They were finger food. This was the answer to my puzzle: the cake mix was all wrong—it had to be more like a cookie mix.”

Left: Turnbull values this wooden French nutcracker as an example of a design solution intrinsic to the object’s structure—what she calls “pure architecture.” Right: A textile designed by Alexander Calder

Courtesy Larry Bullis for Sara Little Center for Design Research/Tacoma Art Museum

During her long career, this same anthropological approach has allowed her to come up with freezer-to-oven dishes made of Pyroceram, a Corning material developed originally for missiles, design bedroom furnishings to help patients with cognitive disabilities regain control of their lives, invent rope candies to give kids a dietary supplement of soybean protein, and create antipollution masks for 3M made of nonwoven fibers. Along the way she gathered an impressive collection of artifacts from around the world—dishes, baskets, bowls, vases, trays, tools, dolls, designer clothes, fabric samples, and more—which she donated in 1974 to the Tacoma Art Museum, in Washington, where she had moved to follow her husband.

Between 1965, when she married James Turnbull, and 1988, when they moved to Palo Alto, California, to seek treatment for his brain cancer at the Stanford Medical Center, Turnbull kept as busy as ever with her consulting work. She would fly to Europe one week and Japan the next, dispensing advice, lecturing, and earning her share of awards in the design field—including a Trailblazer Award and a fellowship from the National Endowment for the Arts. So it’s no wonder that, almost as soon as she appeared on the scene in Stanford, she was hired by the graduate business school. Her husband died in 1991, but Turnbull has made Palo Alto her permanent home, living in a one-bedroom apartment that’s not much larger than her former Lombardi Hotel pad.

Though her teaching schedule is full, she manages to keep in touch with the business world. Academia is not a refuge for her. “I tell my students that the chairman of a company who listens to their ideas and says, ‘Yes, I think we can do it’ is as much part of their design process as anyone,” she says. “I want them to assume right from the start that the client is automatically as creative as they are.”

Students flock to her classes and lab to learn to create “cool new things,” as former student Patrick Sagasi explains. Now a product manager at Adobe, he still uses what he calls her “why-why-why-why-how” approach. “It’s about asking why enough times to dig down to the root of the problem,” he says. “You don’t want to design products that fix only superficial symptoms.”

For an assignment to design a wake-up device, for example, he and his teammates, Linda Kuo, Maria Olide, and Hua Ji, had to figure out (1) why traditional alarm clocks don’t work, (2) why their waking stimuli fail to rouse people every time, (3) why both body and mind have to be activated together for one to awaken, and (4) why setting up the clock is as critical as turning it off. The final prototype looks like a whimsical cube with feet. Setting it and turning it off requires an intricate realignment of body parts. The device gets you up by calling upon your mental alertness and your sense of play.

Stanford MBA Norito Ibata, who is now a retail operation director with Starbucks in Japan, praises her ability to ask the right questions. “Sara always asks me, ‘Norito, why are we talking about what we are talking about?’ She always reminds me of what’s important.”

Many of her students are sure to become enlightened CEOs who think creatively about design. In the meantime, Turnbull says she can’t wait to rush to the office every morning, “because I am 83 years old, and I cannot die until I set the stage for human values in commerce.”