November 18, 2014

Susannah Drake: Ecology as Architecture

Architects tackling the unseen will shape the future of their profession.

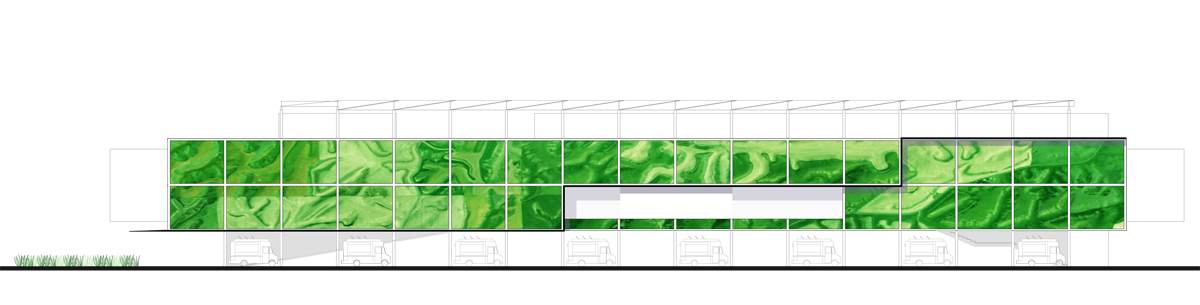

BQ Green

A proposal to put green spaces on the Brooklyn Queens Expressway (BQE) in South Williamsburg, New York City, the project typifies how Drake deftly leverages policy and existing infrastructure to reintegrate nature into the city. The BQ Green can create space for an open green area that includes baseball and soccer fields.

All images courtesy dlandstudio Architecture + Landscape Architecture PLLC

At the Brooklyn office of the landscape architecture firm dlandstudio, growing things are never out of sight. In the little backyard, white hydroponic towers have bright green seedlings of kale, basil, and bush beans slowly taking root. These are the successful experiments for the firm’s 9,000-square-foot vertical agricultural green wall—the largest in the world—planned for the Milan Expo 2015. Less successful experiments lie abandoned nearby. “Those were designed for growing garden plants,” says the firm’s principal, Susannah Drake, “not for agriculture.” Upstairs, in the dining room of Drake’s home, one of her coworkers stops to check in on a rescued bird that’s growing its first feathers in the safety of a cardboard-box nest.

What Drake practices in her office, she preaches for cities around the world. “The way we operate,” she says of her firm’s mission, “is to create a more direct relationship between people and ecology.” In dlandstudio’s hands, this relationship is formed in complex and often unseen ways.

One of the firm’s many daring proposals is a plan for Brooklyn’s extremely polluted Gowanus Canal, an infamous EPA superfund site. Dlandstudio’s Sponge Park will be a green corridor along each side of the canal that will not only help clean it up, but also open up new parts of the neighborhood for local residents. After five years of relentless pursuit, the award-winning project was finally given funding last year for a pilot section of the park, due to open next year. (The firm is so thrilled with this triumph that visitors to the office get a sponge as a takeaway gift.)

Marshes

Economics and ecology come together in Marshes, which will be New York State’s first wetland mitigation bank. It often doesn’t make sense for developers building on waterfronts to mitigate wetlands on-site in dense urban areas. Now they can contribute to the regeneration of a degraded wetland on Staten Island.

Drake has the true idealist’s eye for such win-win situations, turning the hard, sometimes noxious, infrastructure of our previous industrial century into petri dishes for a new kind of urban ecology. “I really deeply believe in the theories of Richard T. T. Forman, an ecologist who was one of my professors at Harvard,” she says. “Richard introduced me to the idea of corridors. Transportation rights of way can become interesting corridors for wildlife in the city. If there are 7,000 miles of highways that run through the cities in the United States, that’s an opportunity for really cleaning up the environment.”

For a start, dlandstudio has its sights set on the most controversial of all of New York’s highways—Robert Moses’s darling the Brooklyn-Queens Expressway (BQE). When a section of the BQE was to be renovated, at a huge cost, Drake couldn’t see why some of that funding shouldn’t be used to create a new green landscape. The studio’s design, BQ Green, will cap a trench in South Williamsburg to create playing fields and open space for a Hispanic community that had been divided by the expressway.

U.S. Pavilion

Dlandstudio is designing a giant agricultural wall for the American Pavilion at the Milan Expo 2015.

BQ Green reunites city populations with nature, but does so within an invisible network of public policy, advocacy, and a strategic proportioning of advantages to all stakeholders. This venture has the blessings of city councilwoman Diana Reyna, and the cooperation of several city and state agencies, convinced—no doubt—by Drake’s talent for talking about urban regreening in brass-tacks terminology. “If you use forest-service data, you can claim that planting 350 trees can give you a $50 million gain over ten years, in terms of water management, air-pollution control, and cooling,” she says.

That’s the kind of mutually beneficial equation that Drake likes. When she participated in The People’s Climate March in New York City this past September, she asked that an anti-oil company chant be changed from “Pro-Science, Not Profit,” to “Pro-Science for Profit.” Fighting for ecology and climate change will generate economic value, even if that isn’t immediately visible. “We should figure how to capture that value,” she says, “and use it to make greater environmental interventions in cities.”