March 27, 2020

A Campus for the 2022 Asian Games Blossoms in Hangzhou

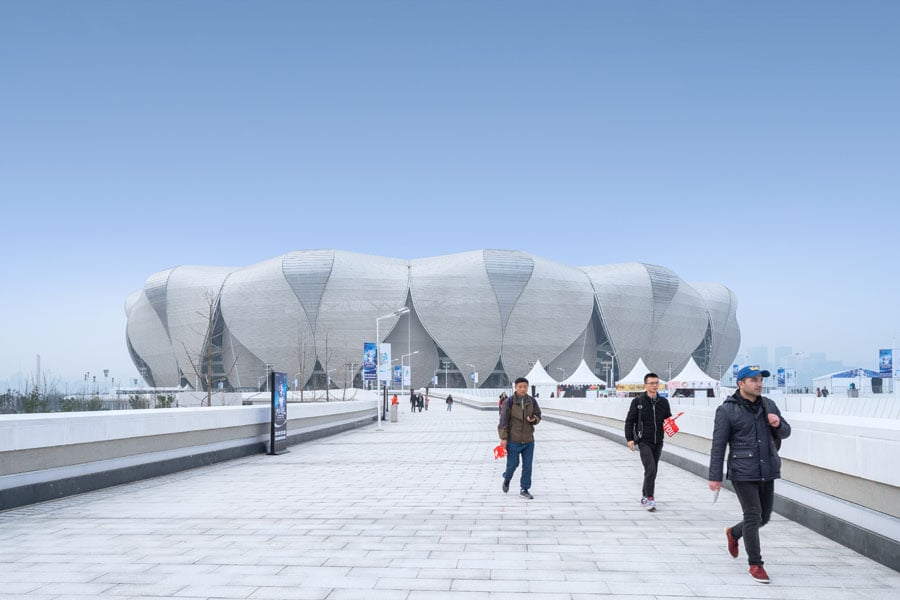

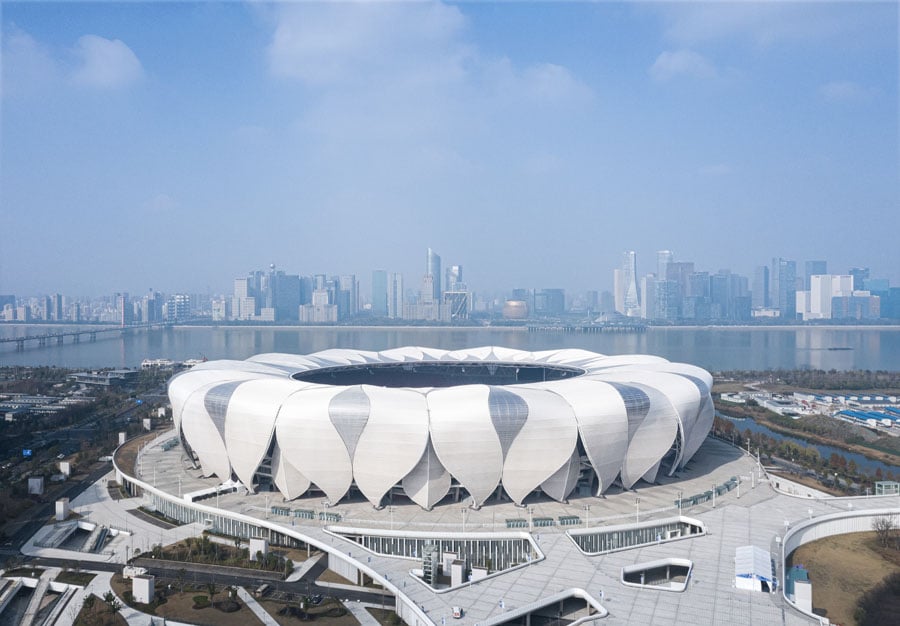

The complex sprawls over a 4.3 million-square-foot project site—with an 80,000-seat, lotus-inspired stadium at its center.

A new multipurpose Olympic sports center in Hangzhou, the capital city of Zhejiang province, offers a glimpse of how China’s architectural landscape is evolving. What was once an unfettered creative playground for the exotic and sometimes downright bizarre has shifted into something more considered, with sustainable, innovative, and context-specific architecture on the rise.

“It is no longer a case of ‘build it and they will come,’” says Robert Mankin of architecture firm NBBJ, who won the project through a competitive bid process in 2009. “Here our municipal client was very conscious about not creating something just for show. They wanted to go beyond the conceptual, to make it something of Hangzhou.”

The complex, which will serve the 2022 Asian Games, sprawls over a 4.3 million-square-foot project site on the Qiantang riverfront. At its center is an 80,000-seat stadium featuring a gleaming facade of 28 pairs of entwined steel petals—a reference to the nearby West Lake’s famed lotus flowers, bringing traditional motifs together with new architecture.

“Second-tier cities like Hangzhou are very exciting because they have a different scale and distinctive personality,” Mankin says. “Hangzhou has a beautiful lake in the center of the city and a wonderful history with villas, temples, and walkways. We wanted to keep a sense of the spirit of the city.”

NBBJ partner Jonathan Ward says that parametric modeling during schematic design was key to refining the light, open, and welcoming human phenomenological experience. The system allowed for the architects to make quick and efficient changes, avoiding traditional “build-test-discard” methods and enabling a reduction of steel by around 67 percent when compared to similar stadiums.

“Getting proportions right in terms of massing and scale was very important and we were able to build in more and more intelligence, modifying the design and making quite complicated changes in parallel with the engineers, BuroHappold Engineering,” Ward explains.

Though the petals’ double curvature is complex to fabricate, the petals were designed to use repeating modular elements that ease their on-site assembly.

Reflecting a growing trend to enhance stadiums, which today are expected to accommodate more than just sports, the stadium was designed for multiple uses. There are two levels for spectators, and a basement retail level that connects with a nearby transit station, restaurants, a cinema, and exhibition and convention centers. The architecture retains an interesting perspective from both within and without, avoiding the more usual inward-looking, fortress-style stadium structure.

Pedestrian circulation throughout the site operates over three levels and links an adjacent 10,000-seat NBBJ-designed tennis stadium through a landscaped network of pathways, gardens, and sunken spaces and courtyards, part of the master plan also conceived by the firm. The petal language of the larger structure carries over into the tennis stadium, connecting the two buildings visually.

“We thought very carefully about how people would inhabit the place when an event is not going on, so instead of inhospitable paved plazas there are meandering pathways that interact with the landscape and water,” Mankin explains.

Perhaps one of the most promising signs of change is that the poor workmanship which has plagued contemporary buildings in China—the price of construction at breakneck speed—reportedly does not appear to have been an issue here.

To some extent this may be because the project was awarded over a decade ago; in the years since, Hangzhou has focused its attention and budget on a number of other major building initiatives, giving the architects who worked with local architectural firm China Construction Design International time to collaborate more closely with the contractor on fine-tuning the design and keeping an eye on quality.

While Mankin agrees time has been on their side, he is adamant about a significant improvement in the understanding of sustainable design and building quality when it comes to cultural landmarks.

“We have seen a growing sense of civic responsibility where a world-class, high-performing building is just as important as creating an icon. Ten years ago these issues were not even part of the conversation,” he says.

You may also enjoy “Gensler Creates a Showcase of Sustainable Design Near Shanghai.”

Would you like to comment on this article? Send your thoughts to: [email protected]