October 2, 2018

AHMM Transforms the University of Amsterdam With a Dramatic Canal-Framing Feat of Engineering

The British firm totally revamped an re-skinned two massive Modernist buildings, creating a new welcoming pedestrian environment in the process.

“The whole project really was about legibility,” explains AHMM’s Simon Allford in the atrium of his recently completed University of Amsterdam project, as a lost student approaches to ask for directions.

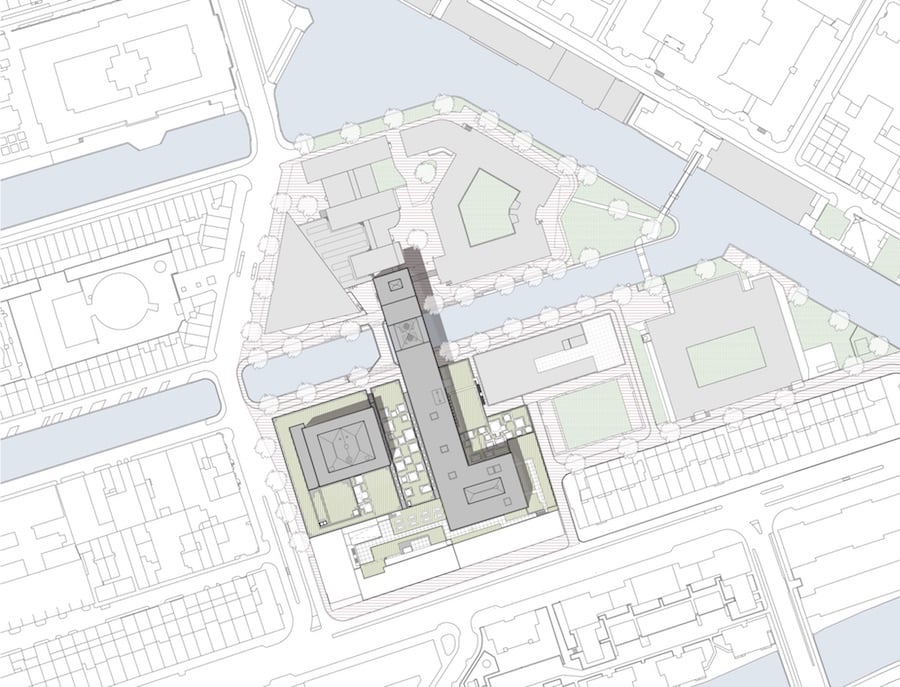

It’s the start of a new academic year and fresh-faced students are learning the routes through the university’s Roeterseiland Campus in the south east corner of the city’s famous canal ring. Home to the faculties of business, social studies, and law, the campus was designed in the late 1950s by Norbert Gawronski, a Polish-born Modernist who fled to France during WWII and eventually settled in Amsterdam where he would become a municipal architect.

Although Gawronski’s original master plan was never completed, two of its massive structures were realized: an 11-story tower and podium for the mathematics department (known, inspiringly, as “REC A”) and an 11-story L-shaped block (“REC BCD”) spanning the Nieuwe Achtergracht canal for the chemistry department.

Typical of the period, these Modernist buildings featured curtain wall facades and interlinked, raised walkways to separate pedestrians from traffic at ground level. Gawronski’s structures were highly ambitious in scale and complexity, but also disorienting with low-ceilinged corridors and gloomy water-side underpasses.

After the chemistry and math departments left this complex for separate facilities in 2006, the structures were freed up for different departments, previously dispersed across the city, as part of a broader (and controversial) consolidation effort. The university named London-based firm AHMM the winner of an international competition to open up the interiors of the ‘60s-era buildings and refocus pedestrian traffic at canal level. Nearly a decade later, the firm’s revamp is a “reinterpretation” that “echoes the history of the building,” according to Allford and project architect Yuk Ming Lam.

The massing of Gawronski’s two original buildings are largely unchanged (their brawny structure allowed the architects to “mess around with them,” according to Allford), although both have new, smoother facades and significant interior alterations. The base of the tower, REC A, connects to a new ground-floor atrium which, in turn, leads to the longer REC BCD structure.

This canal-spanning block has had four stories scooped from its underside in a heroic feat of engineering. This move, referred to as the “cut” by Allford and Lam, has created a dramatic void that frames the city. It creates a ghostly interplay between the Modernist megastructure and the surrounding urban fabric, and is a surprisingly poetic moment from the usually pragmatic firm.

Beneath the “cut,” a new pedestrian bridge-cum-plaza repeats the form of a typical canal crossing, albeit with a slightly more generous width to allow for students to hang out, and benches in place of railings prevent locked bikes clogging up the space. On a sunny September afternoon, the bridge is a buzzing cliche of campus-life: furrowed brows and animated gestures co-exist with rushing book bags and cigarette smoke.

The south end of the bridge leads to the new ground-floor atrium, the renewed University’s central point of navigation. This double-height, top-lit space connects REC A with the adjacent REC BCD and, despite one student’s confusion, is a legible and welcoming point of first contact with the University.

Exposed concrete throughout continues AHMM’s penchant for stripped-back interiors that leave room for future adaptation—an inevitable aspect of higher learning environments. The podium of the REC A tower contains teaching spaces across three scales (lecture halls and two variations of seminar room) plus large circulation spaces that are gradually being furnished as “study landscapes” (i.e. informal spaces for students). The upper levels contain Amsterdam Law School. Its orthodox floor plan (outward-facing offices oriented around a central core) offer rare views out across the low-lying city.

Crossing back through the main atrium over to the tower’s rectilinear sister volume, REC BCD, large internal voids have been cut out of pre-existing circulation spaces, countering the previously claustrophobic feel. Here departments within the Faculty of Social and Behavioral Sciences are clustered vertically to create more dynamic and varied movement within the building than that of its predecessor.

A large glazed cafeteria acts as a central social space to this canal-spanning block and almost appears to float above the “cut.” In fact, it hangs from an enormous truss that has been left exposed in a muscular moment of engineering braggadocio.

Considering the complexity of the pre-existing campus, AHMM’s work here is impressive (and already winning prizes). It’s not subtle, but it is respectful to the doomed Gawronski masterplan while updating it with the sensibilities of a modern urban campus.

Such deference seems to have paid off in the form of praise from Gawronski himself. After touring the building, the architect, now in his 90s, sent Allford a postcard reading: “How fortunate I am that ‘my child’ can develop into such a handsome being under your sensitive hands and mind!”

You might also like, “With the ‘White Collar Factory,’ Stirling Prize–winning AHMM Bets on the Industrial Past to Inspire Future Workspaces.”