May 9, 2022

An Exhibition and Book Give Different Perspectives of Potter Edith Heath

The OMCA exhibition, curated by Drew Johnson along with Volland, connects to OMCA’s three main interests: science, art, and history. It’s not easy to integrate all three along with the story of Heath Ceramics and a biography of Heath herself in just two modest galleries. Including three dimensional objects and graphic images there are 244 items in the show. About eighty of those are ceramic pieces.

Edith Heath and her husband Brian moved to San Francisco in 1942 and Edith, trained as an art teacher, learned pottery and began making her own housewares, which were exhibited in 1944 at San Francisco’s Legion of Honor Museum. By 1947, the Heaths set up their own production facility on the top floor of a former garage in Sausalito. Around the same time they bought a potato hauler barge and joined Sausalito’s bohemian houseboat community. Within a few years they had floated their home to a lot they purchased in nearby Tiburon. The business continued to grow with further production refinements and they built their own factory in 1959 with local architects Marquis & Stoller. The company remains a California staple, with over 200 employees and yearly revenue of over $30 million.

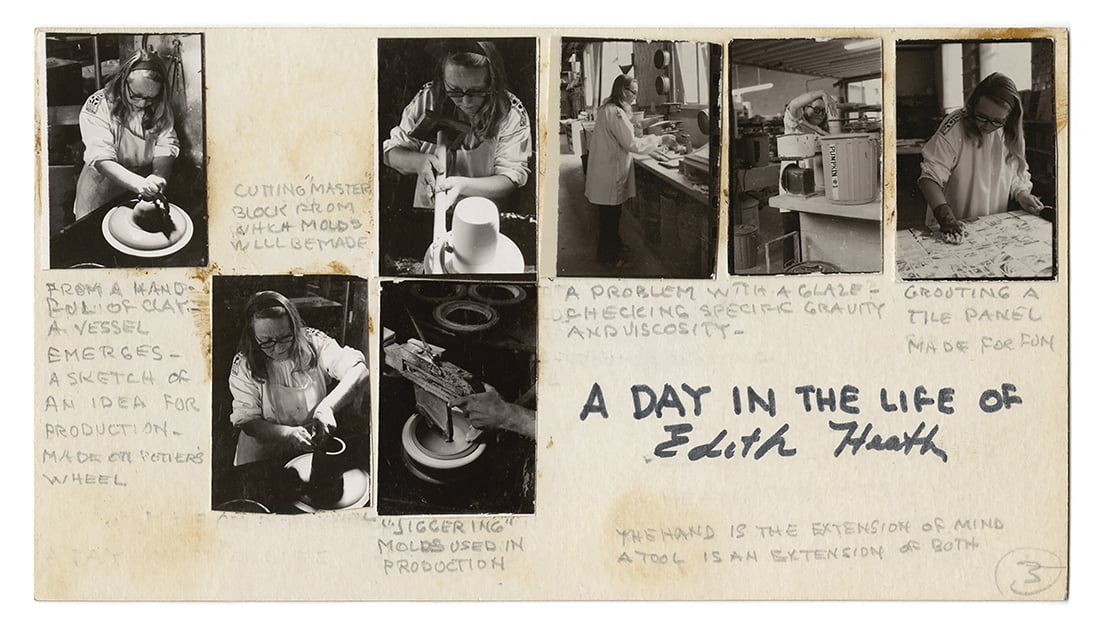

For science nerds, the show features lots of examples about what makes clay clay. One of the simplest explanations is a photograph of a collage made by Edith entitled “Grandchildren of Granite.” Likewise, her work with geology and chemistry results in one of the most apt wall headings: “Edith the Alchemist.” Also on view are her various notations comparing clay bodies, test clay recipes, glazing experiments, and even a photo of testing breakage.

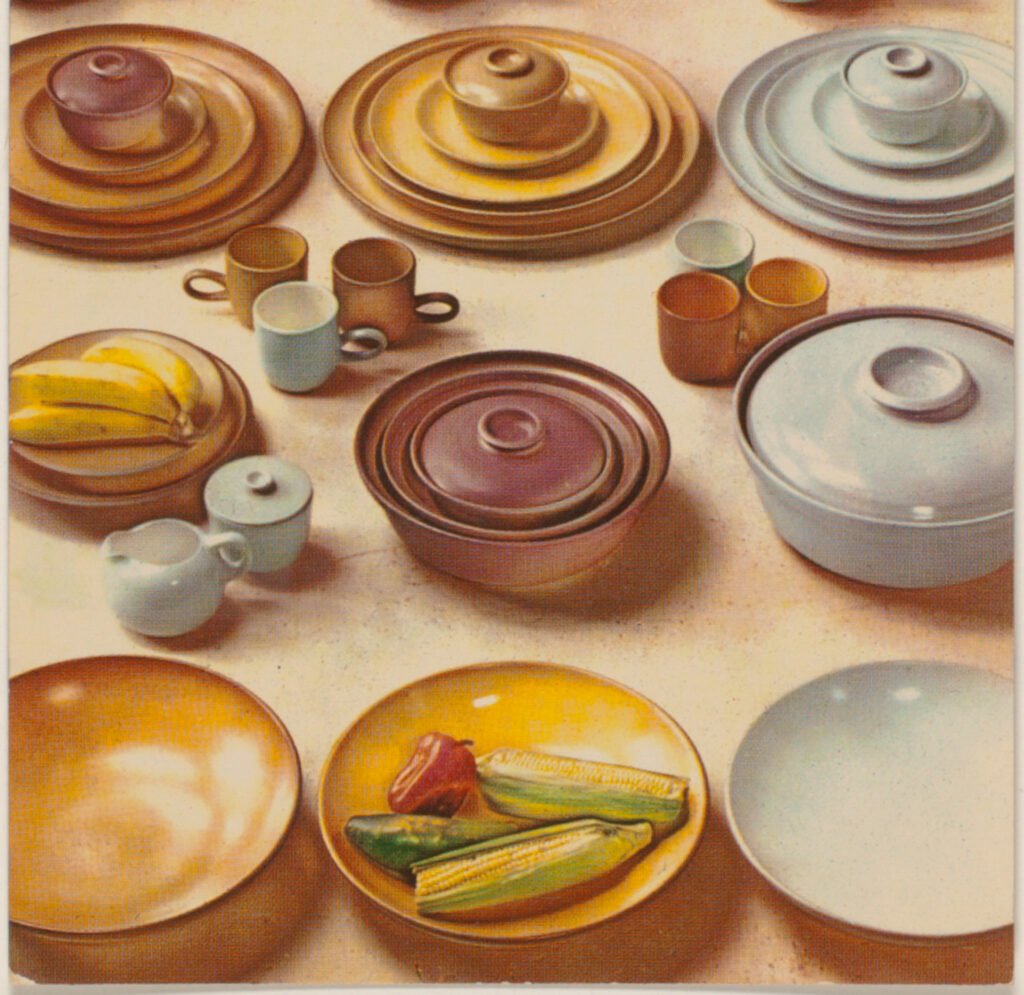

One of the specific challenges of a ceramics exhibition is embodying the tactility and fragility of clay. The museum handles this beautifully by making a custom-made jigger wheel (a tool for shaping ceramic pieces), available so visitors can touch it and get a sense of how her company made their pieces. The curators highlight how little contrast there is between handmade and production ceramics—earth toned teapots, coffee pots, cups, plates, and more—by displaying similar vessels together on two separate shelves. In a simulation of a weekend gathering in Heath’s garden, a wood picnic table from the era displays an informal setting with Heathware and even a custom-made Heath tile table. On a more personal note, Edith’s informal yet rarified style can be seen in a casual cotton dress designed for her by close friend Evelyn Royston, standing in the display.

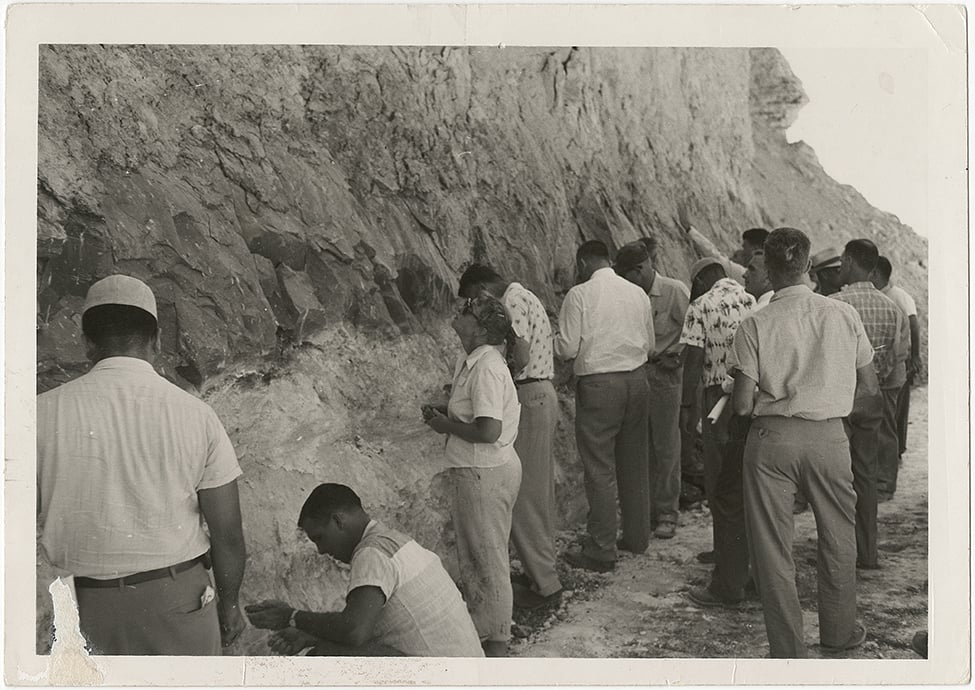

The exhibition includes not only glazed earthenware, an early core of the company’s output, but also glazed tiles and structural blocks (Heath had hoped these would be used for affordable housing and other building projects) that attest to her ongoing experimentation with ceramics for new uses. A few of her original sketches and paintings also show her early artistic talents. One simple drawing depicts her husband at the wheel of their Citroen on one of their many drives to explore California’s clay pits.

In addition to transforming clay, Heath was also mixing progressive politics, the ideas and teaching methods of the Bauhaus, philosophy, and humane economics into her life and work. She was a thinker whose material was clay, wrestling with existential questions about purpose, contribution, and ecology. In one of the book’s most interesting chapters, “The World is Written in Clay,” Volland analyzes several drafts of Heath’s 1950 talk, “What Makes A Potter Good,” as she was transitioning to production line pottery. Heath’s writings, Volland points out, were very much like her ceramics: the process involved constant experimentation and exploration. Volland also connects the idea that the long formation of clay and the long life of Heath products were directly related in Edith’s vision.

Heath wrote a poem as a part of a 1971 talk to members of the AIA:

Primordial rock fragmented

by rain and snow

dispersed to form clay and sand

oxides of iron

molecules of felspar

eons later

the potter

gathers to-gether, re-combines, recycles…

from a handful of mud,

spun or pressed

behold

a vessel… a tile

fused,

as in the ancestral magma,

minerals long separated are united again, shaped for human use.

Another area that the book explores in much greater detail than the exhibition is the utopian thread from the Bauhaus to Heath’s factory, and her last experiments. Artist and architect László Moholy-Nagy, who taught at the Bauhaus, was an influential figure in Heath’s Chicago art circles, most specifically at the Glenwood Park Training Camp in Batavia, IL., where Edith met Brian. The couple’s concern about social equity can be seen in the beautiful, humane design for their Modernist Sausalito factory, and the company’s desire to pay a fair wage. Brian even invited union organizers into the factory (although a subsequent unionization attempt resulted in a strike). Before the Heaths started the business in the late 1940s, Edith taught at the California Labor School, a Marxist institution. In Heath’s oral history at the Bancroft Library, she spoke about how she hoped her ceramic production methods could be used for affordable housing. Like any good business owners, the Heaths were always seeking ways to increase productivity and efficiency; but maximizing profit was not their end goal. This is why experimentation could flourish.

The OMCA show gives viewers a taste of Heath’s remarkable life and accomplishments—her design, experimentation, and production. But even more inspiring is the new book’s revelation of her desire to build a philosophy of artistic creation that would lift a family’s experience at home and an individual’s experience at work.

Would you like to comment on this article? Send your thoughts to: [email protected]

Latest

Profiles

The Next Generation Is Designing With Nature in Mind

Three METROPOLIS Future100 creators are looking to the world around them for inspiration.

Profiles

Zoha Tasneem Centers Empathy and Ecology

The Parsons MFA interior design graduate has created an “amphibian interior” that responds to rising sea levels and their impacts on coastal communities.

Viewpoints

How Can We Design Buildings to Heal, Not Harm?

Jason McLennan—regenerative design pioneer and chief sustainability officer at Perkins&Will—on creating buildings that restore, replenish, and revive the natural world.