May 13, 2014

Architect David Rockwell Sketches Out The Ideal Stadium

Often the designer of choice for mega events, David Rockwell imagines the ideal design of a stadium.

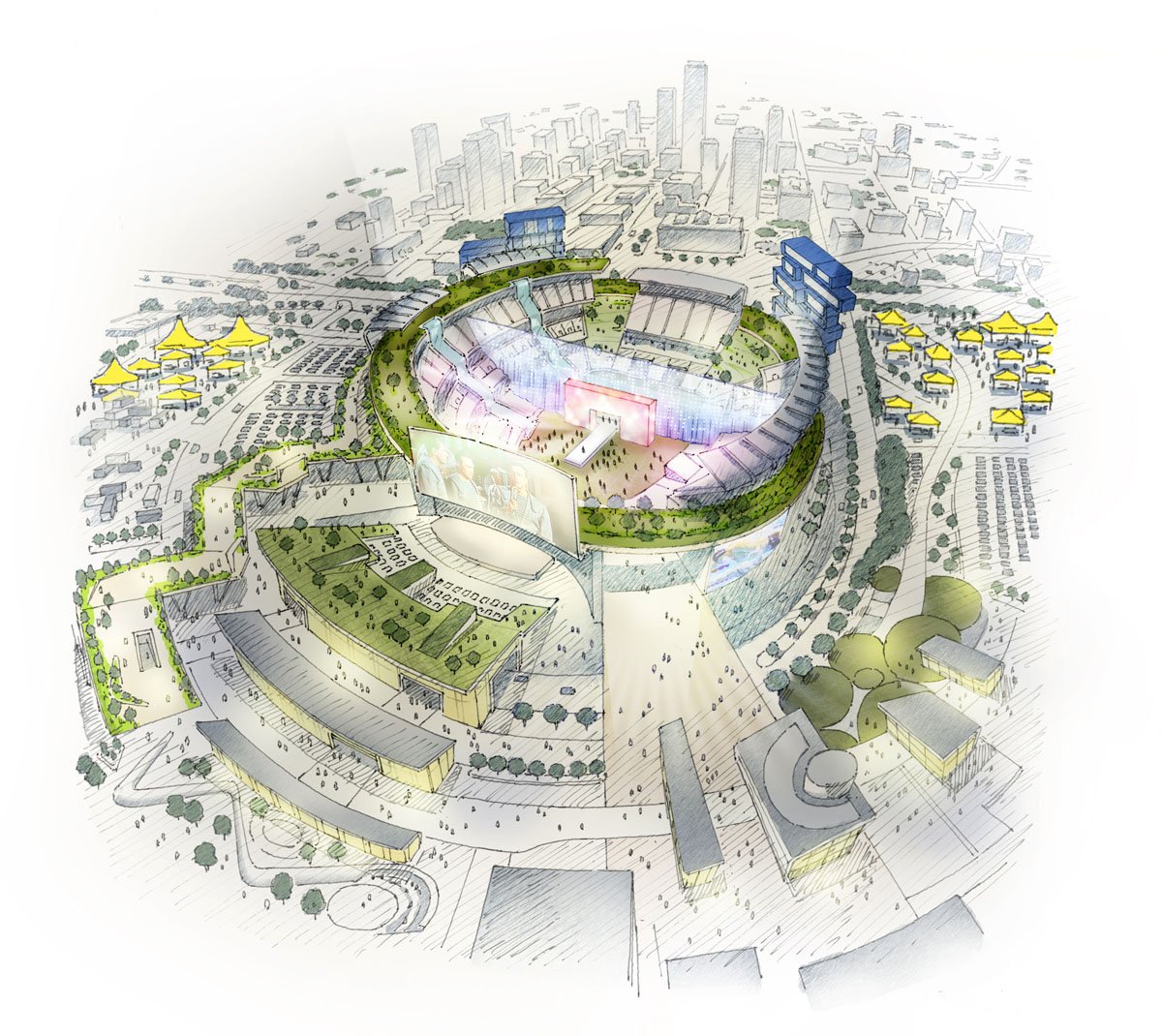

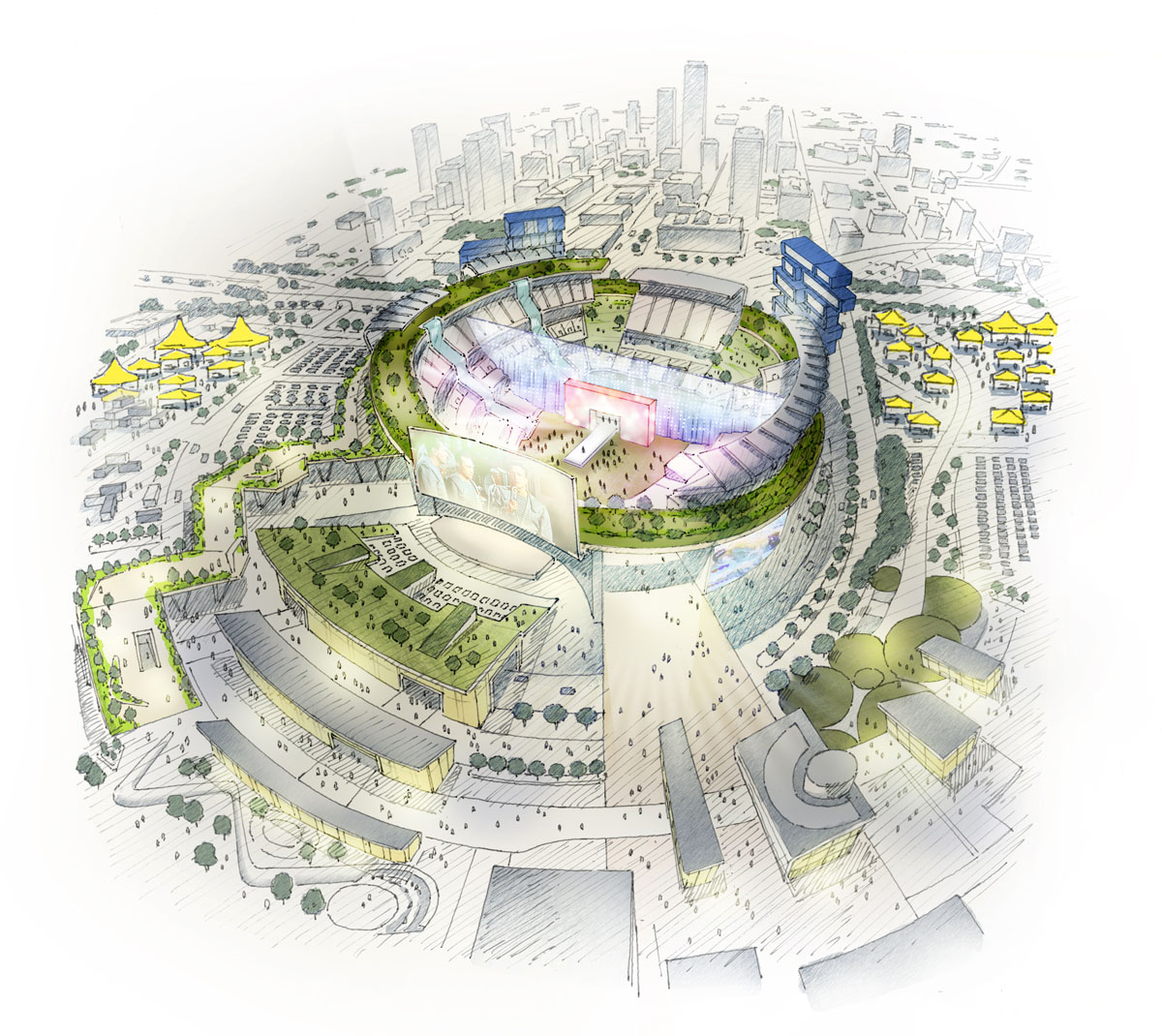

Rockwell’s ideal stadium design emphasizes public spaces and community integration.

Illustration and renderings courtesy the Rockwell Group

David Rockwell has spent most of his career engaged in the art of spectacle. (It is, not so coincidentally, the title of a book he coauthored with Bruce Mau.) Because of his long history creating restaurants, hotels, exhibitions, and stage sets—performance spaces of all types—we asked him to tackle a larger, but related, design problem: the stadium. How do you make these huge facilities more urban friendly? His solutions range from the deliberately speculative (a temporary water park on non-event days) to current best practices in stadium design.

The Problem

“The problem is a pretty easy one to identify,” Rockwell says. “These mammoth buildings remain unused for most of the year. But cities derive a certain amount of civic pride from them, because they’re containers for these incredible rituals conducted on a massive scale. So the question becomes: How do we envision a stadium that provides a suitable platform for these big events, but can also become a part of the public realm when it’s not being used as a stadium?”

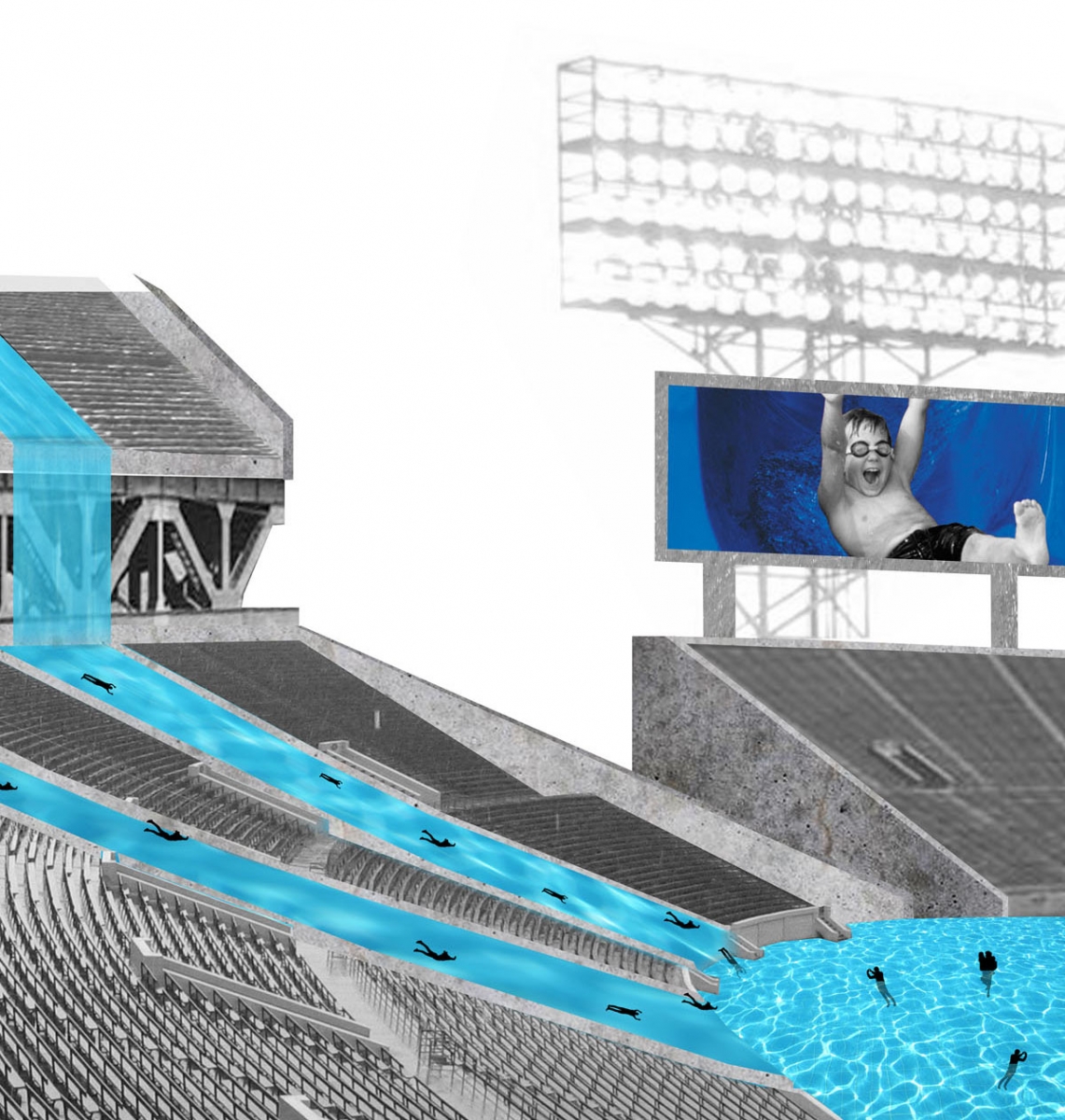

One of the off-season uses for the stadium include a gigantic water park for summer recreation.

Activate the Edges

“One of the first things we did was look at the existing infrastructure and land-use patterns of stadiums. Are there any ways to take advantage of that? You’ve already got circulation of the four quadrants. Those could easily lead to small, low-rise buildings—student housing, temporary work space, community and fitness centers—directly adjacent. The introduction of live/work space could activate the no-man’s-land around the stadium, by potentially triggering more residential development, restaurants, and retail shops nearby. You can also think about the field itself being flexible-—on non-game days it could be open to the public, as a park.”

When the home team is away, local markets and food trucks would occupy empty parking lots.

Asphalt Jungle

“Parking is one of the biggest challenges. For most stadium sites, the moat of parking is a necessary evil, so we approached it a couple of ways. Our blue-sky approach, which is very expensive, creates a partially submerged parking garage, with a sloping green roof that faces a large community movie screen, the back of which is the stadium scoreboard. But there might still be a need for additional parking. How do you activate those spaces? I think you can intersect the parking with temporary structures to create open-air markets. Look at Union Square in New York City—it’s reinvented every day. With a very small amount of infrastructure, you can create a fantastic community space. Additionally, utilizing the parking area for non-game-day events may offset the cost of the parking garage.”

Breaking Down the Scale

“These are big buildings. Either you cele-brate that scale or mitigate it. We’re doing a little bit of both. One thing you can do to address scale is play with the ground plane, as SHoP did at the Barclays Center in Brooklyn. As with many theaters, fans enter at mid-level and burrow into it. You can also break down the scale, as we choose to do here, by placing a series of buildings and parks around the exterior, sort of knitting the bigger building into the urban fabric. And you can make the building more transparent, more permeable. Rafael Viñoly’s football stadium at Princeton is very open to the surrounding campus and was incredibly well received, in large part because of that transparency.”

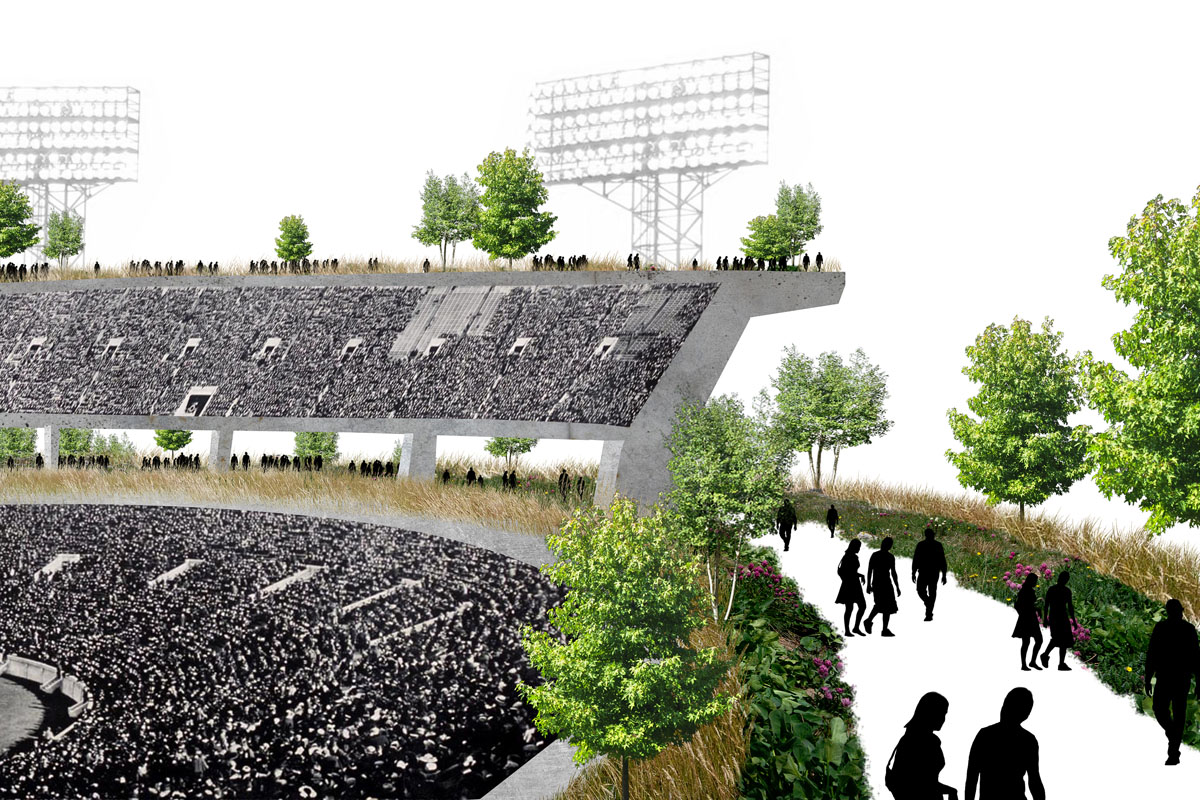

The stadium’s elevated park would offer glimpses into the stadium and, more importantly, views to the surrounding neighborhood.

Transforming the Skyway

“The stadium skyway is a kind of mash-up, partially inspired by Heinz Field in Pittsburgh, where Steelers fans gather on the spiral ramps during games to watch the action. We’ve imagined the skyway as a landscaped area that not only weaves around the stadium, providing glimpses of the game, but also weaves through other parts of the neighborhood, acting on non-game days as a park and urban amenity. Antoine Predock’s Petco Park in San Diego has something similar: a fully accessible park, open year-round, just behind the center-field stands.”

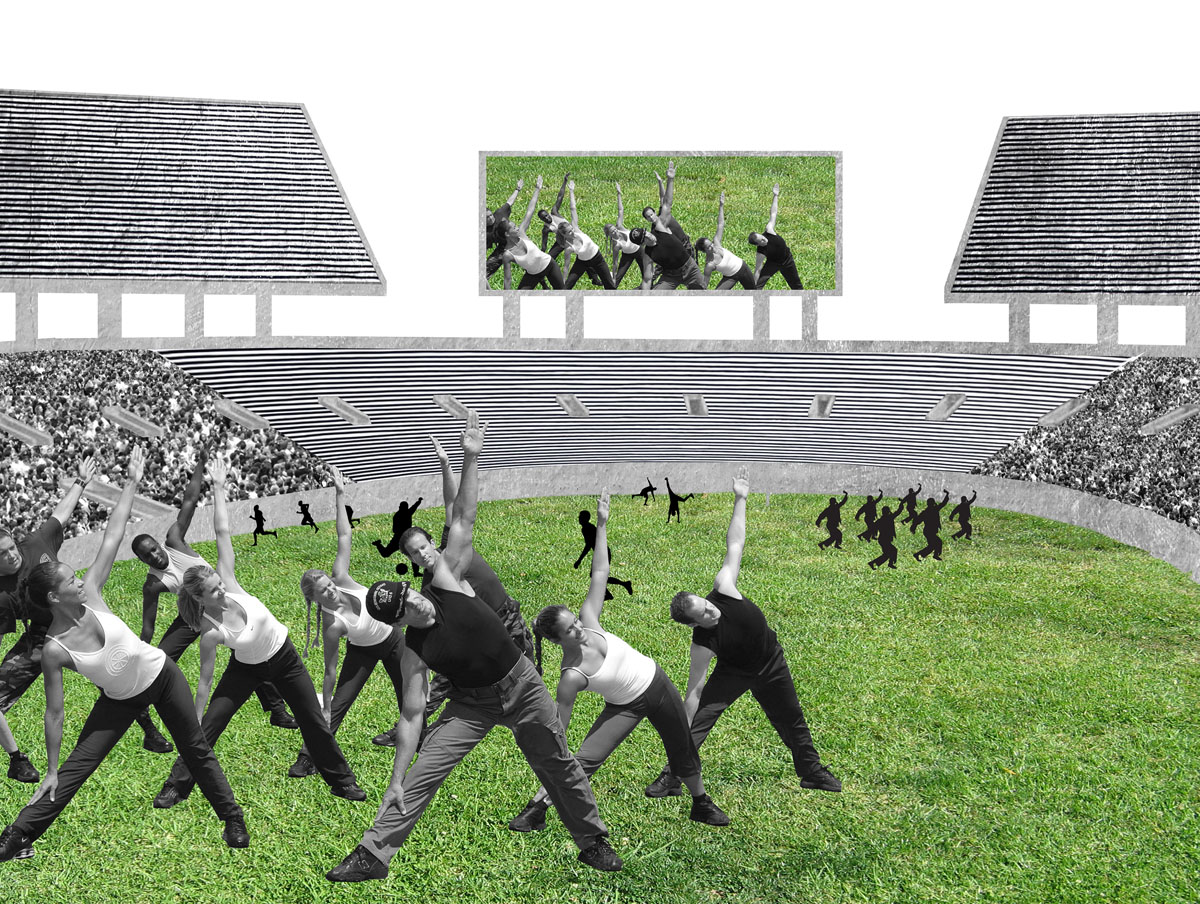

On off-days, the stadium’s field would be repurposed and given over to regular public use.

Reprogramming the Space

“Most musicians don’t like performing in stadiums, even the stars. If they can fill the seats, they’d rather do five nights at Madison Square Garden, where they can control the sound and experience. So, unless it’s a rare act that can fill 75,000 or 80,000 seats, stadiums are compromised spaces for a concert. But I do think there’s a way to design multiple stages within the infrastructure of the stadium to create a festival event. We also envision using a large screen to divide the stadium bowl in half for more presentational things, like fashion shows. Recently we designed a temporary 1,200-seat theater for TED, inside the Vancouver Conference Centre, so the footprint of a stadium might afford even more opportunities for multiple venues.”