February 3, 2013

Firm Adopts Grasshopper, Changes Its Entire Outlook

Elba Morales takes us through the complexities of the design process

As we wound down our a charrette, an exercise somewhere between a Top Chef “quick fire” and a game of “exquisite corpse,” we remembered seeing flickering pixels, oversized movable louvers, folding organ-like planes, and stretching ribbons. Our research yielded a number of innovative precedents—both theoretical and built—from architects and engineers experimenting with movable facades around the world. We had examined automated fins and shading umbrellas, tessellated screens and adaptive fritting from ABI, the homeostatic façades from Decker Yeadon, and the Aegis Hyposurface from Goulthorpe, among others. But it was not enough that these façade components moved, either by means of carefully controlled computerized programming or by more rudimentary manual, hydraulic, or mechanical means.

The movement that we were trying to describe was different. It had to be tied to performance. It had to respond to the sun. As Mike Hickok often said, it had to behave “more like a plant, less like a machine.” With our newly acquired understanding, how could we propose a future in which shading devices would deploy and contract biomimetically, like the artificial muscles we studied, in response to the sun? Then we had a rude awakening. How could we even begin to tinker with these shapes with our limited experience, with the kind of software that had the capabilities to produce what we needed? Clearly we had found ourselves at the convergence of technology, media, and representation. We needed to make leaps in all three. As Lisa Iwamoto describes on her book Digital Fabrications, our design had to inform and be informed by its modes of representation and production. We had to go beyond, way beyond, the limitations of what we traditionally produced in-house and do it at the fast pace of a design competition. At once we were dealing with modeling software shortcomings, researching smart materials, studying artificial muscles, defining performance, contracting out the scripting of algorithms, buying software, and storyboarding the presentation to determine deliverables and staff allocation.

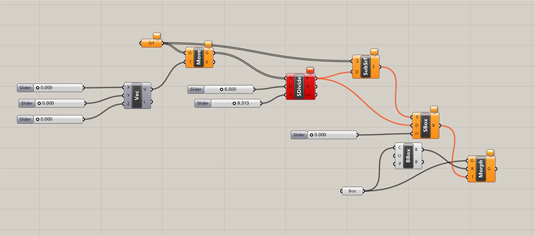

Mike Fischer[ii], a fifth young designer was brought on board, contracted to work side by side with our team to help with computational modeling and scripting. We shifted to Rhino, a NURBS-based modeling software that would allow us to conceptualize, tinker, and control our shading strands. While developing the component, we needed to test it across the façade. Mapping it and remapping it to control its size, density, and openness required formulas—a lot of formulas—which we crunched in Grasshopper.

In the meantime, our knowledge of actuated polymers was growing. We came across the YouTube videos of a team at ETH Zurich led by professor Manuel Kretzer that produced ShapeShift. We extrapolated aggressively. In their thesis, ETH students had been able to refine artificial muscle experiments by engineers, and were building and assembling their own electroactive polymers and actuators into larger shapes with the appearance of woven, curvy planes that expanded and contracted biomimetically. There were blogs, links to research networks, and free “how to’s” on responsive, adaptive, smart materials that had the dynamic qualities found in nature. At the confluence of our research into smart polymers, the ability to control and experiment with the shading strands through algorithms, and the elegant work from ETH, we came up with our Smart Solar Strands. These one-story strands would deploy, block, and filter the sun when needed, positioning themselves as if following its path. When shading was not needed the strands would collapse, align with the curtain wall mullions, and allow for an unobstructed view out into the exterior. Their movement is slow and emotive, similar to the mimosa pudica plant that opens and closes when touched.

To further test and fine tune the shape and scale of the shading strands and the surface qualities we wanted to convey, we produced a series of animations. Using Maya we set up interior and exterior views to position ourselves inside the office space, in order to understand up close the qualities of the shading façade we were creating. We ran a series of test animations with accurate coordinates and observed how the sun affected our building throughout the day and the seasons. After hours, we took over our coworkers’ computers, loaded up software on their machines, and set up a farm of 15 computers to render the thousands of frames needed for these animations.

Rob Holzbach’s Storyboard

Despite the competition requirements that our submission be printed, we knew that the only way to convey both the emotive qualities of our adaptable Smart Solar Strands and our integrated approach had to be a video—another technology we had little experience with. What would we show, how would we organize it? Rob Holzbach, a senior designer[iii], took on the role of “movie director.” Through intricate, hand drawn images on a 10-foot long segment of trace paper, he created our storyboards. Under the radar and without seeking prior approval from the principals, the team embarked on the production of a short movie as our competition entry. We remembered Mike Hickok telling us, “Better to beg for forgiveness than to ask for permission.” We were on.

Our story is as much about process as it is about product. Through it all we discovered that working at the confluence of technology, media, and representation, paired with cross-disciplinary research, opened a small window into what disruptive innovation could be through the achievement of the unexpected. In our next post, Mike will assess the impact that our efforts had within our office and on the broader community.

Elba Morales, Associate AIA, LEED AP, is a senior associate at Hickok Cole Architects in Washington, DC and the lead designer on the Office Building of the Future competition, a national ideas competition sponsored by NAIOP.

[i] Lisa Iwamoto, Digital Fabrications: Architectural and Material Techniques, Princeton Architectural Press, 2009 [ii] Michael Fischer worked with the team on a contract basis, helping with the scripting of formulas and creating animations. [iii] Rob Holzbach is an Associate Principal at Hickok Cole Architects