April 14, 2010

Book Review: The Grid Book

The Grid Book wants to show us that the history of building, composing, computing, mapping, lending, painting, printing, trading, and writing—the history of modern existence, in other words—is really a history of the grid.This is ambitious. By a bit too much, as it turns out. The author, Hannah Higgins, isn’t quite able to map out […]

The Grid Book wants to show us that the history of building, composing, computing, mapping, lending, painting, printing, trading, and writing—the history of modern existence, in other words—is really a history of the grid.

This is ambitious. By a bit too much, as it turns out. The author, Hannah Higgins, isn’t quite able to map out all the facts she needs, nor always plot a convincing narrative course between the ones she does locate. The result is a breezy survey, accessibly written and sometimes provocative, but lacking the rigor and regularity of the grid itself.

Still, The Grid Book deserves attention for its glimpses into the secret life of this ever-present meme, which is central to the image of modern networked society. Going “off the grid,” after all, is an act of cultural as well as technological subversion. And aren’t all grids made to be broken?

Higgins defines the grid as “an organized set of modules that allow for manipulation and creativity.” Her first chapters, which postulate brick walls and tablet writing as proto-grids that have been with us for thousands of years, suggest that this modularity has an instinctual appeal to humans. City plans and map projections formalized the grid as a field of intersecting lines, which gave us the Mercator projection. This gridded worldview is everywhere—and The Grid Book is at its most intriguing uncovering some of the less obvious manifestations.

.

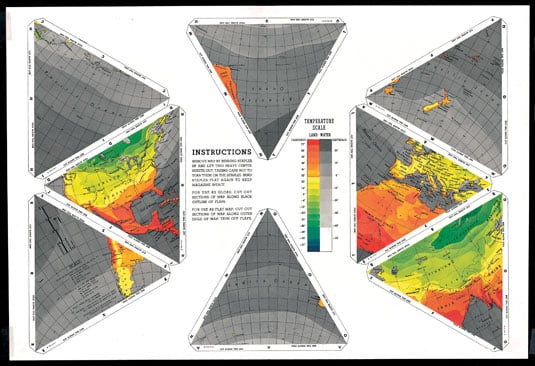

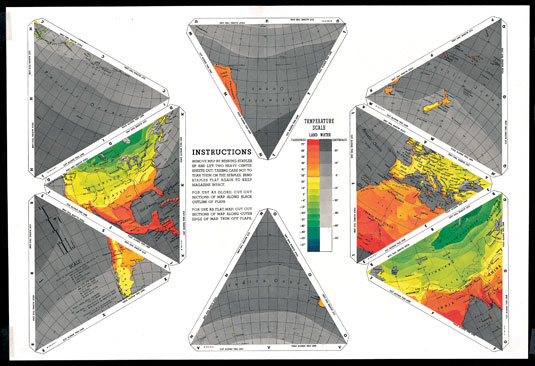

Mapping the globe onto a grid distorted the Earth’s true size and scale. Buckminster Fuller’s Dymaxion Map attempted to remedy this by fitting the globe into a hybrid square-triangle grid that could be unfolded in various configurations. (View a larger version.)

Mapping the globe onto a grid distorted the Earth’s true size and scale. Buckminster Fuller’s Dymaxion Map attempted to remedy this by fitting the globe into a hybrid square-triangle grid that could be unfolded in various configurations. (View a larger version.)

.

Higgins analyzes the quotidian Excel spreadsheet as the latest evolution in dual-entry bookkeeping, the visual realization of modern capital flows. She explains the grids behind page and screen layouts, movable type, and even the geometry of letterforms themselves as unseen agents of what Marshall McLuhan called “typographic man.” Even the commodities of everyday life are nested into grids—as dockside shipping containers stacked into perfectly orthogonal piles. And the connectivity embodied by container ships and sea lanes parallels the movement of digital information upon the conceptual grid of the Internet, which Higgins traces from the computer punch card to the post-millennial grid-computing movement (now better known as distributed or cloud computing.)

Higgins also reminds us that the motivating force of the industrial revolution was to produce textiles (grids of fiber, after all) at lower cost, and cleverly links fabric to computing by pointing out that polygon-based modeling software follows the logic of a fishnet stocking, “emphasizing the calf muscles and ankles by translating them into greater and smaller squares.” Perspectival projection—the source of the computer code that renders digital models into life—would be impossible without grids to calibrate foreshortening and organize the picture plane.

.

Leon Battista Alberti’s “veil” of gridded strings embodies a desire to apply the grid to three-dimensional space.

Leon Battista Alberti’s “veil” of gridded strings embodies a desire to apply the grid to three-dimensional space.

.

Marring this fine synthesis are several easily avoidable errors. These include the statements that Louis Kahn’s National Assembly of Bangladesh is a brick building (it is poured concrete) and that the 1807-1811 Commissioners’ Plan for Manhattan laid out Central Park (it wasn’t created until 1853). Likewise, The Grid Book’s omissions can be startling, as when the two paragraphs on Descartes fail to mention the grid coordinate system that bears his name.

Higgins, as a modern-art historian writing for an audience keen on design, is most undermined by the lack of illustrations that would bolster her arguments. Too many are tangential and trite: stock photos of skyscrapers and power lines, Duchamp’s Nude Descending a Staircase. Easily obtainable materials that would enhance the text, such as Renaissance architectural drawings, Buckminster Fuller’s Dymaxion Map, and plans of Philadelphia and Washington, D.C., are left out.

This is disappointing because we need more books to be what The Grid Book sets out to be: a scholarly, cross-disciplinary design history for the educated reader. There are too many coffee-table image tomes, exercises in academic esoterica, and middlebrow “The true story of how X changed the world” volumes, and not nearly enough smart reads. Higgins seems to have the tools to write one: broad interests, unencumbered prose, and a willingness to skip over the grid of disciplinary lines. Here’s hoping she returns to the challenge.

.

Dymaxion Map image: Pull-out from Life magazine (March 1, 1943), courtesy the Estate of R. Buckminster Fuller/(c) Time, Inc.