January 8, 2020

At Tel Aviv University, a New Science Building Looks—and Acts—Like a Cloud

A salutation to the two science departments it holds, the Check Point Building’s ephemeral form contrasts with the campus’s more orthogonal buildings.

In Tel Aviv, a monolithic cloud holds court over a university square. A salutation to the two science departments it holds, the 68,000-square-foot Check Point Building at Tel Aviv University evokes the binary world of computers and cloud computing with its distinctive glass-shingled facade.

Positioned next to the university’s celebrated 1998 synagogue by Mario Botta and a 1960s science building, the four-story Check Point Building is home to the Dov Lautman Unit for Science Oriented Youth and the Blavatnik School of Computer Science. Kimmel Eshkolot Architects, the local firm which landed the project after a competition, designed the new campus landmark with the express intention that it stand out. “The volume is more free in its form and floating, in comparison to the very rigid, orthogonal buildings around it,” says cofounder Etan Kimmel. This is Kimmel Eshkolot Architects’ second building on the campus, after completion of the Steinhardt Museum of Natural History in 2018.

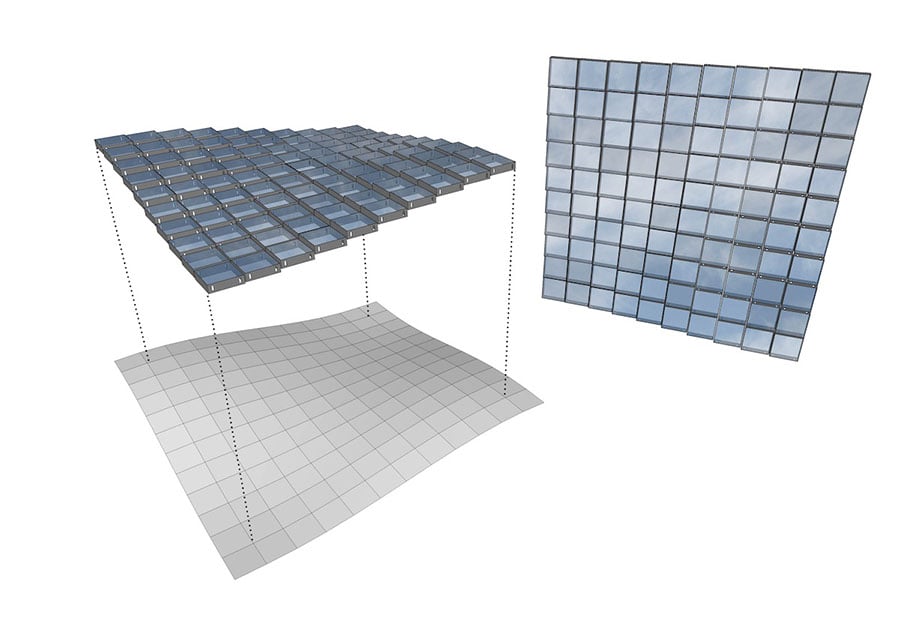

To achieve the dynamic facade, the architects deployed the relatively new technology of parametric modeling—a system that allows architects to change one element of a design and have the entire plan adjust in response. “The mechanics didn’t really exist; we created our own,” notes Kimmel. Five types of 16-inch square glass shingles were used, for a total of 19,000 units. Positioned for a three-dimensional gradient effect and ranging from opaque to almost completely transparent, the shingles are able to change their form in reaction to weather and light conditions. Double-layered, the envelope sandwiches an HVAC system, which draws in fresh air and jets it into the interior. The two layers also enable windows to open without interrupting the singular form.

To service the two independent departments it holds, the building—which houses computer labs, laboratories, meeting rooms, a planetarium, and seminar spaces, in addition to classrooms and offices—has two entrances and two lobbies, each with its own glass atrium linked to circulation on upper floors. Circulation was conceived to engage sociability—a thoughtful suggestion from professors for students who spend large amounts of time in front of a computer. Clustered near two exposed stairs, informal meeting and coworking spaces make “circulation an event,” explains Kimmel.

Throughout, a pristine backdrop of mostly white walls means “people and furnishings and supply the color,” continues Kimmel, who selected “round and soft” upholstered pieces to contrast with the straight lines of the interior architecture.

In twilight hours, the facade also responds to hard-working professors. Their illuminated offices send out an explosion of dispersed pixels across campus that gradually wink out as night falls.

You may also enjoy “Schoolhouse Revival: A New Hotel in an Old School Frames a Scenic Park in Washington.”

Would you like to comment on this article? Send your thoughts to: [email protected]