March 13, 2014

Divides Drawn: The "Paper Architecture" of the USSR

An ongoing exhibition at the Tchoban Foundation charts the development of Soviet architecture.

In the history of 20th-century Russian architecture, there exists a central struggle. In one corner, the Constructivists, champions of light, airy, and functional buildings that drew their power from the social and aesthetic revolutions of the 1920s; in the other, the Stalinist architects, whose thuggish hybrids and clumsy pastiche became the predominant vernacular throughout the Soviet republics. The latter, as we know, eventually came out on top.

Things are rather more complicated, of course, as an ongoing exhibition at Berlin’s Tchoban Foundation argues. Architecture in Cultural Strife: Russian and Soviet Architecture in Drawings, 1900-1953 brings together a total of 79 unique architectural delineations that chart a historical trajectory running from the twilight years of the Romanov dynasty up to Stalin’s death by the midcentury.

The exhibition, says its curator, Irina Sedova, attempts to portray the development of architecture in Russia and then the USSR “as a real process of strife between tradition and avant-garde, between cultural inheritance and new invented forms.” The differences between Constructivism and Stalinism, as the show illustrates, aren’t as clear cut as typical architectural histories would have you believe. There was, at least for a time, plenty of room for nuance between the two architectural cultures.

Despite the exhibition’s timeline, little happened in the years from 1900 to 1920, save for a frenzied, but short spell with Art Nouveau, translated in the Russian context as stil’ modern. This lack of architectural activity was largely due to the turbulence of the time. Two wars, a string of social and military crises, and multiple political revolutions interrupted ordinary construction cycles, preventing anything like normality from taking shape. Meanwhile, the widespread destruction of the country’s built infrastructure wrought by years of bloody civil war created a demand for new projects to replace what had been lost.

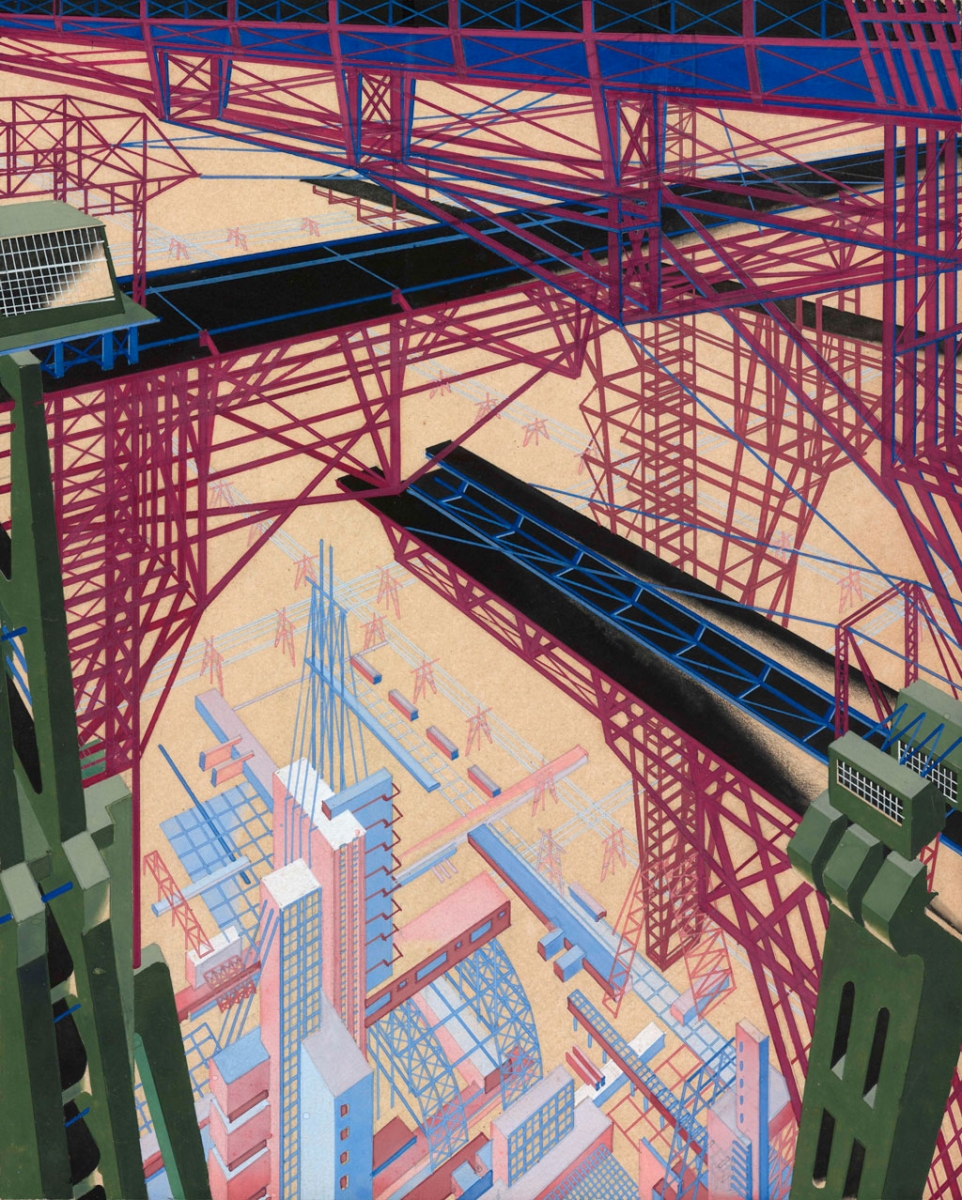

Yakov Chernikhov, Factory building, Ca. 1931, Drafting pen, ink and pencil, 298 x 248 mm

After conditions finally stabilized in 1922, an experimental phase set in. Inspired by revolutionary tendencies in the visual arts—by abstract painting and sculptural constructs—an architectural avant-garde began to cohere. The emerging Soviet avant-garde was hardly monolithic, however, despite certain popular depictions that represent the modernists as one homogenous bloc. Numerous tensions existed between different tendencies within the modern movement, in the USSR as elsewhere. Some, like the Vesnin brothers and Moisei Ginzburg, emphasized a “functional method” of construction; others, such as Nikolai Ladovskii and El Lissitzky, stressed a more formal, speculative approach to design. A few prominent modernists like Ivan Leonidov and Iakov Chernikhov, whose “Architectural Fantasies” feature prominently in the Tchoban exhibit, belonged to neither of these camps, falling somewhere in between.

Yakov Chernikhov (1889–1951), Architectural Fantasy, 1929–33

If one thing united these rival modernist currents, it was their common opposition to the prerevolutionary academic style. The Soviet avant-garde’s relentless propaganda against architectural backwardness won out, and by the tenth anniversary of the revolution, modernism seemed to have prevailed. Quite a few academicians enthusiastically made the switch to more avant-garde forms, dabbling here and there with new materials like sheet glass or ferroconcrete, arranged into asymmetric and orthogonal forms. Aleksei Shchusev, already a renowned architect before October 1917, led the way in this respect, designing structures every bit as unprecedented as the Constructivists. (Shchusev’s third and final version of the Lenin Mausoleum, rendered in granite, is on display at the Tchoban).

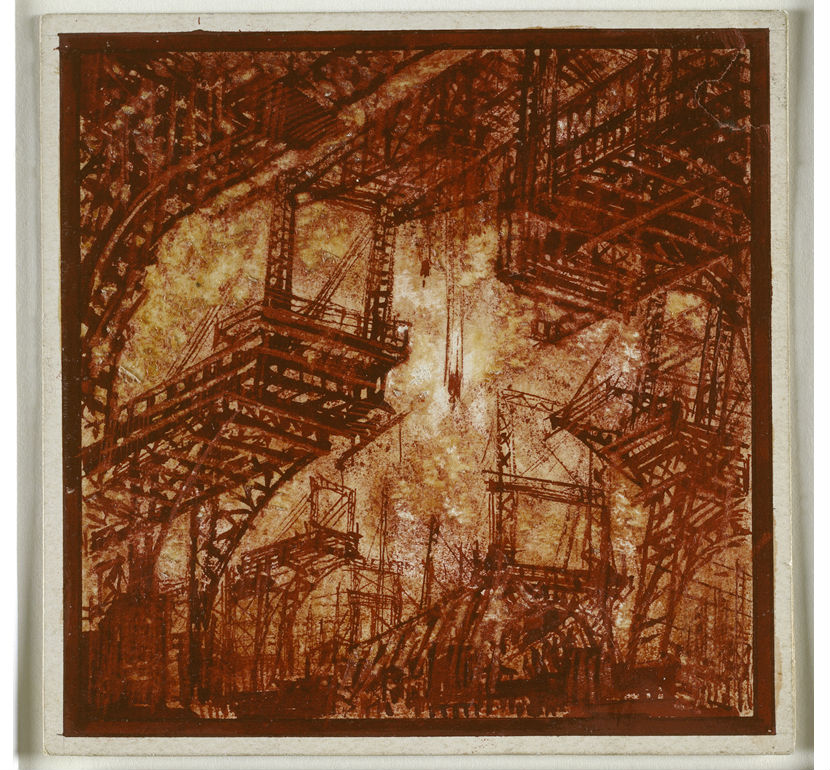

Yakov Chernikhov, Architectural fantasy. View of the enormous portal cranes with semi-circular corbels, 1932-1936, Drafting pen, gouache and lacquer, 105 x 105 mm.

The various autonomous architectural associations, however, lost their independence in April 1932, when they were forcibly consolidated under the umbrella of the Soviet Architects’ Union (or ССА). While avant-garde tendencies remained strong within the newly-formed Union, there were already signs that modernism’s days were numbered. Results had just come in from the recent, high-profile Palace of the Soviets competition, and seemed to indicate that the regime’s aesthetic tastes were drifting toward a kind of oversized neoclassicism. Vladimir Shchuko, Boris Iofan, and Vladimir Gelfreikh submitted the winning entry: a peculiar blend of columns, arches, and statuary on an enormous scale.

But just as it would be misleading to regard Soviet avant-garde architecture as uniformly “constructivist,” so it would also be misleading to portray Stalinist architecture as uniformly “neoclassicist.” Stalinism in architecture drew from a number of historical styles, but did so using modern materials. Gothic, baroque, and neoclassical elements appear in almost equal measure. These showed up not only in built work, but in unbuilt projects as well. Iakov Chernikhov’s Architectural Fantasy: View of the enormous portal cranes with semi-circular corbels (1932-1936), above, seemingly evokes the flying buttresses and pointed arches of Gothic cathedrals. Here they appear amidst iron trusses and heavy industrial scenery, however, set against the backdrop of a burning sky. Chernikhov, as with Leonidov, would retreat more and more into fantastic sketches as time went on—not as a blueprint for future building, but as an escape from the grim reality of Stalinist reaction. Utopianism was not wholly absent in Stalinist architecture; it was just displaced.

Arkady Mordvinov, Vyacheslav Oltarzhevsky, Design for the Hotel Ukraina in Moscow. Perspective, 1948 – 1954. Brush and watercolour over preparatory pencil sketches, white highlights, 1424 x 1267 mm

Boris Iofan, Design for Moscow State University on Leninskie Gory in Moscow. Main façade, 1947, Charcoal on tracing paper, 680 x 895 mm

The Second World War, or the Great Patriotic War (as it was remembered in the USSR), once again disrupted normal building operations. Construction of the Palace of the Soviets, underway since 1937, was put on indefinite hold after the Nazis invaded in 1941, never to be resumed. After the German surrender in 1945, rebuilding commenced in cities like Moscow, long-besieged Leningrad, virtually flattened Stalingrad, and elsewhere throughout the country. Probably the most notable postwar architectural achievements were the so-called “Seven Sisters” of Moscow, high-rises built in a stepped wedding-cake style. In this respect they were not too far off from Chicago Deco, which for reasons of zoning possessed similar parameters. Boris Iofan’s 1947 Design for Moscow State University on Leninskie Gory (above) is exemplary of these skyscrapers. Stalin’s death in early 1953, however, marked an end to this epoch, as the last giants of the “Stalinist Gothic” style were erected.

Taken together, the “paper architecture” on display exercises a strange grip on the imagination. “The significance of ‘paper architecture’ is that it serves as lab material for the creation of new or ‘old new’ forms,” explains Sedova. By highlighting conflictual tendencies in Russian and Soviet architecture during the first half of the twentieth century, the exhibition illustrates the entire range of possibilities (and impossibilities) that seemed to open up in this moment. It therefore affords a brief glimpse into lost worlds: not only the real or historical world in which these architects lived, but the worlds they imagined themselves to be building.

‘Architecture in Cultural Strife’ runs through March 21, 2014.

Ross Wolfe is a writer and historian of Soviet architecture currently living in New York. He blogs at The Charnel House.