October 8, 2018

El Equipo Mazzanti Heals a Gash in Bogotá’s Urban Fabric With a Patchwork of Verdant Gardens

Once the center of controversy, El Equipo Mazzanti’s innovative Bicentenario Park restitches two divided districts in the Colombian city’s historic core.

It’s impossible to experience Bogotá, Colombia, without encountering the aura of Rogelio Salmona. Perhaps more than any architect before him, Salmona shaped the urban identity of this Andean city through poetic, civic-minded buildings. From a small balcony in the late architect’s office—set at the top of a tower of his own design—a Salmona tableau unfurls: directly ahead, the torquing volumes of Torres del Parque, a three-tower residential complex completed in 1970; and to the south, MAMBO, Bogotá’s modern-art museum.

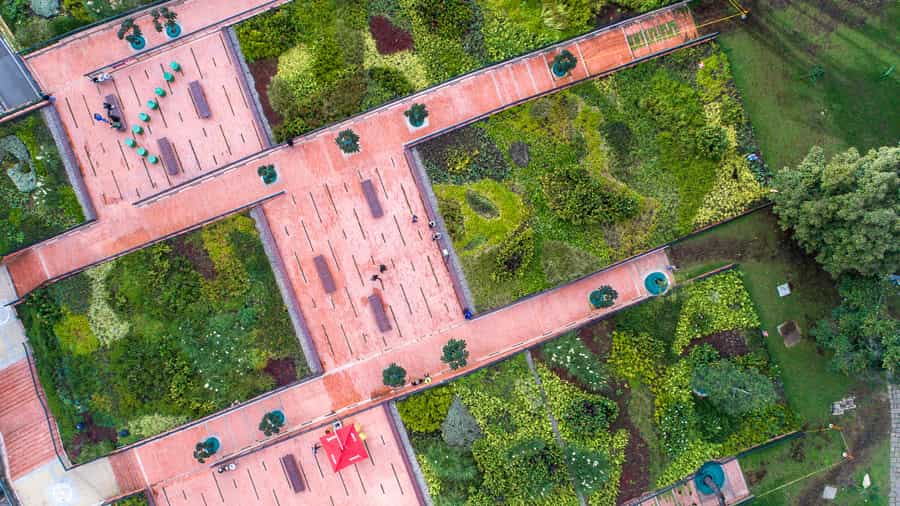

Between these two landmarks, just visible through a canopy of wax palms, is a 21st-century response to Salmona’s Modernist legacy. Bicentenario Park, designed by local rm El Equipo Mazzanti, is an artful fusion of infrastructure and public space. At once a pedestrian bridge and social connector, this verdant two-acre quilt of landscaped brick plazas remedies a critical gash in Bogotá’s historic center. “The park speaks to a new way of seeing tradition,” says Giancarlo Mazzanti, founder and principal of the firm. “It is a proposal to connect us in a more daring way, opening spaces for everyone and for all activities, putting at the center of the tradition a point of reflection, views, and encounter.”

Bicentenario Park, along with the Salmona masterworks, sits amid a clutch of Bogotá’s most treasured places, including the city’s historic bullfighting ring, national library, planetarium, and Parque de la Independencia, a lush public garden created in 1910 to celebrate the centennial of Colombia’s independence. But broad portions of the park were obliterated in the 1950s to make way for Calle 26, one of the city’s primary arteries. Over the years, this division contributed to the area’s dete- rioration and attracted criminal activity. Salmona himself had plans to create a brick plaza in this void, but they were truncated by his death in 2007.

After inviting tenders in 2011, the mayor of Bogotá tapped El Equipo Mazzanti to devise plans for the area’s revitalization. Mazzanti’s vision was formally and conceptually bold: a sequence of geometric pedestrian overpasses to link MAMBO with the isolated Parque de la Independencia. But the proposal soon became the focus of a frustrating and prolonged legal battle, spearheaded by local preservationists—many of them residents of the nearby Torres del Parque—who argued that the design would spoil the area’s historical and horticultural integrity. The quarrel led to a messy court battle, and construction came to a standstill in July 2011. One newspaper went so far as to dub Bicentenario “The Park of Discord.” The project resumed construction in 2014 and was completed in the fall of 2016, nearly nine years after its initial approval.

Today, according to the Institute of Urban Development, the municipal agency that manages the park, Bicentenario serves roughly half a million Bogotá residents in the neighborhoods it touches. Mazzanti’s design consists of eight concrete platforms that span Calle 26. To account for differences in elevation and the height of buses passing below, these broad, elevated terraces are linked to the historic park and MAMBO by means of a series of ramps and staircases. At the park’s western terminus, the platform fans gently into a stepped public plaza along Carrera 7, another major thoroughfare. Mazzanti opted to pave these elevated plazas in traditional red brick, a nod to both Salmona’s architecture and the surrounding city.

In addition to creating a heavy-duty piece of infrastructure, Mazzanti and his team implemented a mix of hardscaped and landscaped zones to differentiate circulation elements from more contempla- tive areas. The team, working with the municipal botanical garden, selected a mix of plants robust enough to survive in shallow earth, yet light enough to avoid affecting the bridges’ structural system: Camouflage-like beds feature slender yarumo trees, spider plants, ferns, fluffy pampas and feathertop grasses, and bright Dutch irises. Viewed from the air, amid its densely packed context, Bicentenario has the appearance of a vibrant jigsaw puzzle.

Despite the early controversy, Bicentenario Park has become a vital civic asset. On any given day, locals can be seen relaxing on benches, having coffee with colleagues, or watching films projected on MAMBO’s facade. Schoolchildren cluster along the steps to have lunch after field trips. Even the once- vocal opposition has quieted. One local columnist, writing for the daily El Tiempo, conceded, “We tend to criticize before the works are done, and when you see the results, few recognize it.”

Salmona himself might have agreed. “As with music, [architecture] reveals itself little by little through reason and dreams,” he said in a 2003 address. “When architecture has gone beyond the constructive act, it is because it has moved us. It has believed in its own time.”

You might also like, “New Queens Park Restores Wetlands That Double as Resiliency Infrastructure.”