September 4, 2024

Elkus Manfredi Transforms a Cold War Bunker into a Children’s Health Institute

“Children’s National set out to build a research ecosystem and clinical spaces to address some of the most challenging cases in pediatrics, which often come through the Rare Disease Institute and are studied at the Center for Genetic Medicine Research,” says Irene Thompson, executive director, real estate and capital planning, for Children’s National Hospital. “We also wanted the campus to be a welcome space for members of the community to be seen in our primary care clinic.”

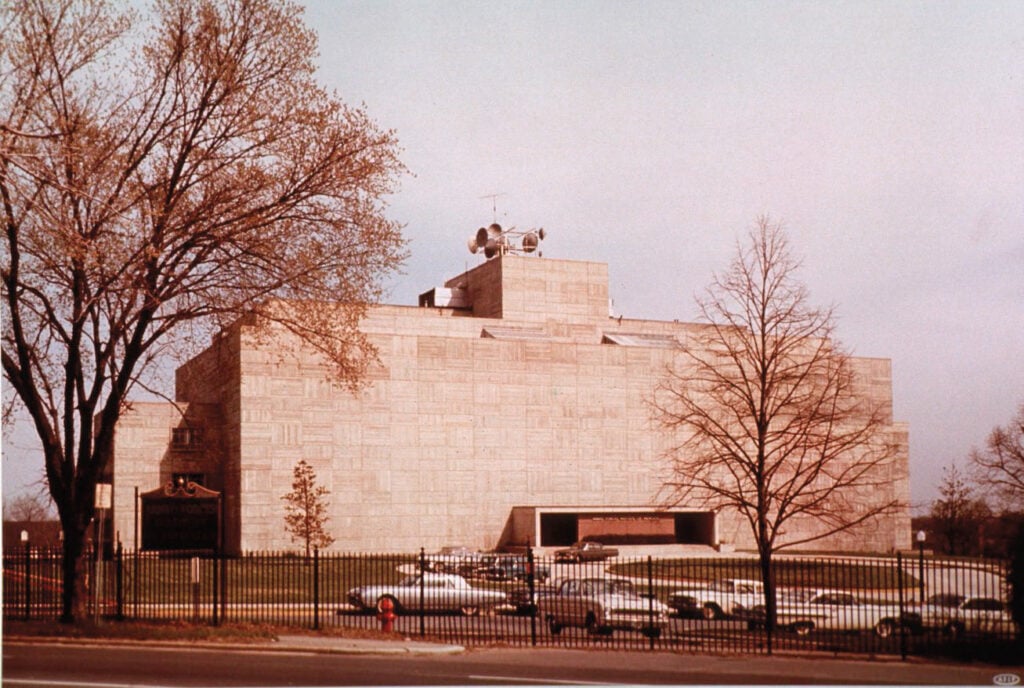

While the buildings, ranging in architectural styles and spanning various eras, had become obsolete, “the existing architecture was really quite outstanding,” says David Manfredi, CEO and founding principal of the firm. The architects took a respectful approach to the design. The largest buildings in the collection—buildings 54 and 54x—received a significant renovation. “We basically took it down to the slabs,” Manfredi says. “Everything, all the infrastructure and mechanical systems, was removed and completely rebuilt.”

Building 54 was completed in 1953 and was essentially a windowless Brutalist bunker with 18-inch-thick walls, designed to contain highly sensitive government research and able to withstand a hydrogen bomb blast on the U.S. Capitol. Needless to say, bringing in light with new windows was a priority. Unfortunately, the preservation board limited the work to the east facade only. “We cut through the 18 inches of concrete to add windows,” Manfredi says, adding that “the proportion, even the shape, of the windows was informed by the checkerboard pattern of the board-form concrete exterior.” In all, the firm added about 6,000 square feet of new windows.

Naturally, the architects updated all the systems and created ADA-accessible interiors. The material palette, to a certain extent, celebrates the history of the building. “We brought some of the board-form concrete inside, but wherever we could, we used wood to make it warm and added pops of color,” says Manfredi. “There’s certainly whimsy in some of the graphics in the building.”

The state-of-the-art mechanical systems significantly improved the project’s sustainable bona fides. “At the time we were designing it, which was 2019, the average national EUI [energy use intensity] for a lab building was 370,000 BTUs per square foot per year,” Manfredi explains. “Building 54 was designed to achieve an EUI of 108,000 BTUs per square foot per year.” A parking garage incorporates a 1.64-acre, 1.148-megawatt solar array that feeds power to the local community.

For Thompson, “we set out to create world-class health-care and research facilities, and we are delighted with how the buildings meet that mission.”

Would you like to comment on this article? Send your thoughts to: [email protected]

Latest

Projects

The Project That Remade Atlanta Is Still a Work in Progress

Atlanta’s Beltline becomes a transformative force—but as debates over transit and displacement grow, its future remains uncertain.

Profiles

WAI Architecture Think Tank Approaches Practice as Pedagogy

Nathalie Frankowski and Cruz García use their practice to help dismantle oppressive systems, forge resistance spaces, and reimagine collective futures.

Products

Functional Beauty: Hardware That Does More Than Look Good

Discover new standout pieces that marry form and function, offering both visual appeal and everyday practicality.