May 14, 2009

Heavy Editing

The new Frank Lloyd Wright exhibition at the Guggenheim represents a remarkable bit of curatorial restraint.

The new Frank Lloyd Wright exhibition at the Guggenheim represents a remarkable bit of curatorial restraint on the part of the show’s organizers. Although the show takes up pretty much the entire building—starting near the bottom of the rotunda with the early Oak Park years and then ramping chronologically all the way to the top and concluding, fittingly, with the Guggenheim Museum in New York (along with a couple of unbuilt projects)—the exhibit is a mere fraction of the Wright archive.

“We have enough material in the archive to mount a show of similar scale every year for the next 110 years,” said Phil Allsopp, the president and CEO of the Frank Lloyd Wright Foundation, at a press event this morning celebrating the show’s opening. The archive contains more than 22,000 drawings, of which about 200 are used in the show. They’re the heart of the show—especially the early ones done by Wright himself, which are rich and evocative—and art in and of themselves. But as you move chronologically up the ramp an interesting thing happens: the poetic quality begins to flatten out as the hand of Wright (presumably) disappears and associates and students take over the drawings, adopting the signature Wright look.

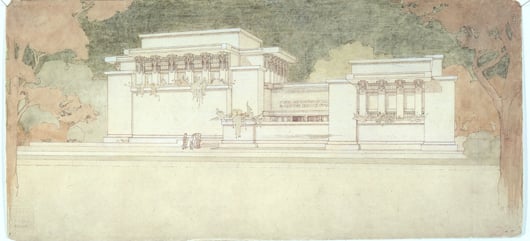

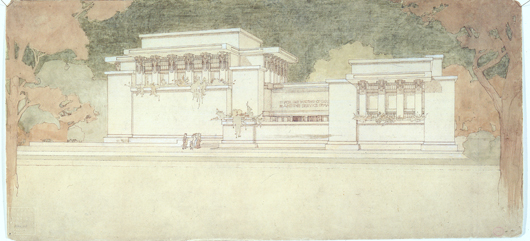

Above: Unity Temple, Oak Park, Illinois, 1905–08; ink and watercolor on art paper. Top: Wright, circa 1959, during construction on the Guggenheim Museum. Images: courtesy the Frank Lloyd Wright Foundation and the Solomon R. Guggenheim Foundation

Above: Unity Temple, Oak Park, Illinois, 1905–08; ink and watercolor on art paper. Top: Wright, circa 1959, during construction on the Guggenheim Museum. Images: courtesy the Frank Lloyd Wright Foundation and the Solomon R. Guggenheim Foundation

The curators—led by Thomas Krens, David van der Leer, and Maria Nicanor of the Guggenheim; and Bruce Brooks Pfeiffer, Margo Stipe, and Oskar Muñoz of the Wright archive—limit themselves to 64 projects, giving each one room to breathe along the long descent down, using Wright’s own architecture to surprisingly good effect (given the building’s often tortured relationship to art). Two galleries off the main rotunda look at Wright’s houses and larger urban projects.

Left: Herbert Jacobs House #1, Madison, Wisconsin, 1936–37. Right: Wright’s unbuilt mile-high Chicago office tower, “The Illinois.” Click to view larger images.

The archival material is smartly interspersed with newly created models done by Michael Kennedy of Kennedy Fabrications and Situ Studio of Brooklyn, including a dramatic “exploded” version of the Herbert Jacobs House (Madison, Wisconsin, 1937) hung by wires. The models perform a neat trick: they give the projects—some famous, some unbuilt—a curiously contemporary feel and serve as a reminder that Wright’s legacy, fifty years after his death, remains a living one.