March 13, 2013

How I Came to Design Anthropologie’s Loved & Hated Paper Vases

Exploring the process of designing

I have satisfied my first order for a large retailer, Anthropologie, and I must say I feel great. I feel great because for young designers, it is increasingly difficult to have our voices heard. And further still, most companies won’t even recognize that you have a voice until you have “proven” yourself. But I did it. The paper vases, Om, that Anthropologie ordered have been loved and hated. I cannot, sadly, tell you why people like or dislike them; however, I can tell you how they came to be and let you judge for yourself.

The concept of OM grew out of research for my graduate thesis at SCAD. While most of my peers had some working knowledge of furniture’s holy three: leather, wood, and fabric, I was more familiar with industrial processes and plastics—my background is in industrial design. To me the smell of leather was foreign. The differences between quarter-sawn and half-sawn wood were lost on me. And the warp of a fabric was indistinguishable from its weft. I was naïve.

But it was this beautiful ignorance that gave me a perspective not shared by most of my peers. I was intrigued by simple things; the things most people take for granted. I was in love with the pedestrian things of our world. So I felt no embarrassment when I informed my professor that I would be exploring the qualities of wood and its by-product paper. And explore I did! I dyed it. I dipped it. I burned it. I pureed it. I mixed it with plaster. I even sewed it (inspired by a pair of Tyvek pants made by Maison Martin Margiela). I did countless studies and tests searching for…I don’t know what.

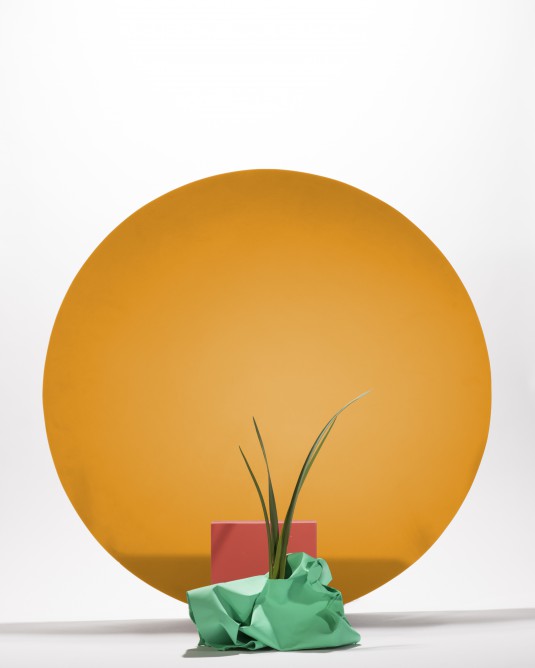

Then, as things almost always happen long after my class and academic requirement to explore had ended, I came to it. I was reading an article on the alterity of felt when I realized that this entire time I’d been attempting to bully the paper, bend it to my will. I had ignored the desires of the material, of the paper. After having this aha-moment my process changed. I would no longer tell the paper what to do; instead I endeavored to see if it had the capacity to achieve what I had in mind. I began bending instead of creasing—I viewed a crease as a command, irrevocable once committed, whereas a bend was a suggestion. I would let these bends and folds create both the aesthetic value of each vase while simultaneously acting as their structure. Through this process of “call and response” each vase became nothing like anything else. The shadows became design elements; the surface of the paper became a canvas for diffused light. I was pleased. But not everyone was onboard. Professors thought they were disrespectful; peers thought they were a joke. Others, though, thought of them as poetry made tangible. I thought of them as the zenith of my process.

Here was an object that was deceptive—it looked like a haphazard thing, when in fact it was the result of a very precise dance. And although they’d been criticized heavily I decided that I wanted to show them in the Mecca of global furnishings. I took them to Milan. It was there in Italy, that they received a warm and pleasant welcome. There they were understood. It was there that Anthropologie saw them and approached me, and there in Milan that I got my first chance. To satisfy their order I had to streamline my process. I needed to balance industry with poetry without sacrificing quality. I had to design and fabricate the tools that would help me produce multiples, and I had to develop an operations system. There were color tests to make sure that the hues I was producing in the latex were vibrant enough. And overnight I had to become an expert on shipping goods. I was a one man operation. And as fate would have it a boutique in Savannah that specializes in designer objects would also place an order for vases while I was filling Anthropologie’s order.

It was pressure, but for so long I’d told myself that this is what I wanted: to make my living as a designer. There were countless nights of no sleep, forgetting if it was Monday or Thursday and becoming a recluse, not seeing friends for lengths at a time. This was the cost of doing business. But it wasn’t all sweat and insomnia; I would make more than sixty handmade vases over the course of two weeks. Through the repetition of production I witnessed the evolution of my routine; the pieces themselves grew in their subtlety and expression. What had once seemed haphazard would finally begin to express the beauty of its raison d’être. After packing away the last vase, I realized I’d found what I unknowingly set out after more than two years ago, when I first started this exploration: I’d found the ability to stake a claim, believe in it, and follow it to its furthest reaches. I am glad. I am proud, and I have no intention of slowing down.

Bradley Bowers is trained in furniture and product design. He sees his objects as souvenirs of “some journey, some bygone experience that I am sharing with you. The fantastic thing about my profession is that it gives me the chance to journey with every person who uses one of my objects.” He adds that his first product, “Om is a flower vase that restores value to an often under-appreciated material, paper…. The folds and creases remind me of the crisp and radiant fabrics found hanging in Old Master paintings.” Photos by Pablo Serrano http://pabloserrano.me/