April 22, 2022

In the Toronto Suburbs, Affordable Senior Housing is Overhauled to Meet the Highest Efficiency Standards

Before its renovation, there was nothing unusual about the Ken Soble Tower in Hamilton, Ontario. The 18-story high rise was built in 1967 to be operated as subsidized senior housing by CityHousing Hamilton, but in all other regards it was just like the hundreds of post-war suburban high rises that sprang up in the Toronto suburbs in the 1950s through the 1970s. Now, however, it’s the largest Passive House–certified residential retrofit project in the world and offers 114 units of deeply affordable (pegged to income) and 32 units of moderately affordable (rents below $1,000 CAD per month) housing for senior citizens.

“When they built suburbs in Toronto, [the developers] built at least two apartment units for every single-family home,” says Graeme Stewart, principal of ERA Architects, who led the retrofit along with fellow principal Ya’el Santopinto. He explains that unlike many other suburban landscapes in North America, in Toronto a combination of private developers and city planners––in thrall to Modernist architects––built suburban housing primarily as rental units in high rise towers outside of the city center.

Since then, the towers have aged and have become a crucial source of affordable housing in Toronto, which like nearly every large city, is experiencing a rise in housing costs and a lack of availability. “When newcomers come to Toronto, this is where they generally live,” says Stewart. “The city has relied on that affordability to make the housing system work. But affordability is now under threat, as housing pressures are going up, rents are going up, and if [a building is in] a bad enough state, it’ll just go offline, and we’ll lose that housing.”

Ten years ago, ERA Architects formed The Tower Renewal Partnership, an organization that preserves and improves some of that vital affordable housing. It was a way for the firm to connect with NGOs, governments, and other institutions to better understand the environment in which their work as architects takes place.

“When we started this, the architecture wasn’t yet possible,” explains Stewart—there was no funding, the developers and building owners were not yet on board, and neither were residents. To restore the towers, the architects had to become activists. “It really was about consensus building and policy development that got us to a point where there were some provincial programs that really kicked it off, and then more recently, federal programs, where they’re now putting billions of dollars towards these types of retrofits,” he says.

Along the way, the Tower Renewal Partnership published several white papers and policy document that illustrate how developers, architects, and community leaders can restore these midcentury residential developments in order to tackle greenhouse gas emissions, build social and economic life for their residents, and eventually transform the neighborhoods with infill housing and additional transit.

Major political victories have included zoning changes to about 500 sites that allow businesses like grocery stores to operate inside developments that had previously been entirely car dependent. In addition, a $15 billion federal commitment to retrofitting 200,000 units of high-rise housing nationwide places an emphasis on those managed by nonprofits.

But Ken Soble, unassuming as it may appear, is something of a watershed moment. As the largest residential Passive House retrofit to date, it began when CityHousing Hamilton’s CEO Tom Hunter approached ERA Architects with a challenge: He wanted to transform their oldest tower, a defunct senior housing block, into a hyper-efficient Passive House building.

“We probably wouldn’t have suggested that, because it’s really ambitious,” admits Stewart, who says that, “when we got in there, there was asbestos everywhere, all of the systems were past end of life––including plumbing. So, we had to redo everything.”

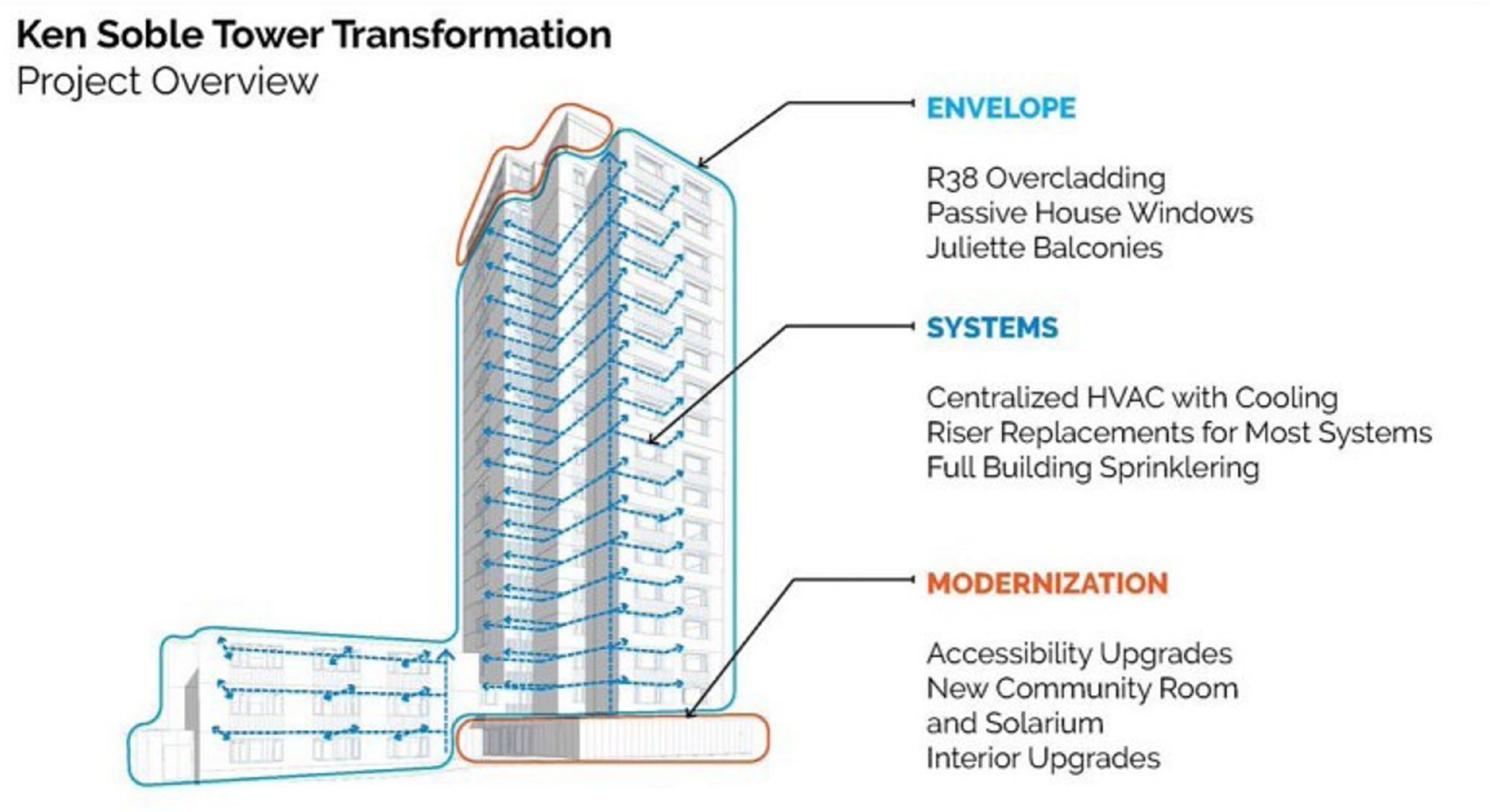

In addition to gutting the building and replacing mechanicals, ventilation, and fire safety systems, a heavy winter coat made of low embodied carbon mineral fiber was wrapped around Ken Soble’s 18 floors. Meanwhile, triple-glazed windows were affixed to the outside of the existing window opening to account for the new difference in wall thickness.

New landscaping and amenities also help improve quality of life for the residents—the penthouse was transformed from a laundry room to a common area, and an outdoor terrace was added on the ground floor.

In terms of performance, the building is a knockout—achieving 94 percent reduction in greenhouse gas emissions. Stewart says that even if the building were to lose heat in the coldest Toronto winter, residents would be comfortable inside for four days, compared to about four hours in a standard building. However, warming summers also required a more robust cooling system, which was accomplished through central dehumidification, two operable windows in each unit that can be opened to create a cross-breeze, and ceiling fans to create a comfortable operative air temperature without needing to fire up the building’s air conditioners. Additionally, each unit is direct ducted, with clean, fresh air coming in from the outdoors—a critical concern because of COVID-19, especially for a building with older, more vulnerable residents.

But the tower’s most meaningful carbon reduction came from simply reusing the existing concrete structure. Stewart says that the firm’s embodied carbon study found that had it been torn down and replaced with a new Passive House–certified building, it would have taken 180 years of operational carbon savings to make up the carbon lost in the concrete itself.

Stewart hopes that the building can shift perceptions on what’s possible for affordable housing and what’s considered sustainable, “High performance is always considered luxury and high tech, but what we need is high performance and affordable. The budgets were pretty lean on this project, and this is the approach we took to be able to get it to perform and meet budget.”

Would you like to comment on this article? Send your thoughts to: [email protected]

Related

Profiles

Zoha Tasneem Centers Empathy and Ecology

The Parsons MFA interior design graduate has created an “amphibian interior” that responds to rising sea levels and their impacts on coastal communities.

Viewpoints

How Can We Design Buildings to Heal, Not Harm?

Jason McLennan—regenerative design pioneer and chief sustainability officer at Perkins&Will—on creating buildings that restore, replenish, and revive the natural world.

Profiles

Inside Three SoCal Design Workshops Where Craft and Sustainability Meet

With a vertically integrated approach, RAD furniture, Cerno, and Emblem are making design more durable, adaptable, and resource conscious.