October 2, 2024

Kengo Kuma Designs a Sculptural Addition to Lisbon’s Centro de Arte Moderna

A Museum in a Garden

“When we visited the site, we immediately knew the garden should be the protagonist of the project,” says Kuma, when I spoke to him at the museum’s opening. “We chose to create an in-between building, where people can feel and see the gardens but still be in a protected space,” he says. The result is a swooping canopy based on the Japanese idea of an engawa, or sheltered walkway that not only shields the exhibition spaces within from the harsh southern light, but also becomes a “room” in its own right. There are also beautifully framed views of the garden from underneath it as well as from the museum’s new partially underground gallery with its line of clerestory windows.

The canopy is over 328 feet long and 50 feet wide, and another smaller canopy swoops in the other direction over the entrance. The new portico is clad in ultra-thin ceramic tiles above and dehydrated ash below, both sourced and produced in Portugal. According to Kuma, the portico works as both an anchoring point and philosophical metaphor for what a contemporary museum should be.

“Our concept was freedom, openness, and transparency,” he explains. “You can do anything in the engaw—have big parties, lectures, art exhibitions. It’s also a place for people to rest, relax, and meditate.” And the sort of space that is sorely needed post-COVID he adds, as well as “a bridge bringing nature and humans together.”

A Poetic Landscape

This theme of connection and continuity is also embedded in the ethos of Vladimir Djurovic, whose firm VDLA Landscape Architecture, was also part of the competition bid. “This garden is a little masterpiece, and the foundation has been nurturing it for over 50 years,” he says. “When we won the competition, I just wanted to continue what had already been done.” The original hard-angled modernist design was by landscape architects Gonçalo Ribeiro Telles and António Viana Barreto. Over the years, the garden became softer, more organic and poetic explains Djurovic as it has bedded in and been restored and upgraded, most recently by Telles himself in 2002. “The mystery and the beauty of the garden came out as it evolved over time.”

By planting indigenous species, the landscape architects say the garden will become almost entirely self-sustaining in just a few years. Just like Ribeiro Telles and Viana Barreto before them, they have created curved pathways, water features and more intimate areas as well as a large central gathering place with a pond for people to congregate. Referencing the concrete slabs that abound in the older part of the park and provide stepped access over water, Djurovic used organic-shaped granite slabs around the engawa as it is more durable. The signage, bins and edges of the planting are made of corten steel that will, again, require very little upkeep. As soon as the CAM reopened last weekend locals were queuing in droves. They had clearly missed the building but now it is not only brighter, bigger and far more accessible, it comes with an extra segment of lush informal garden open to all.

Would you like to comment on this article? Send your thoughts to: [email protected]

- No tags selected

Latest

Projects

The Project That Remade Atlanta Is Still a Work in Progress

Atlanta’s Beltline becomes a transformative force—but as debates over transit and displacement grow, its future remains uncertain.

Profiles

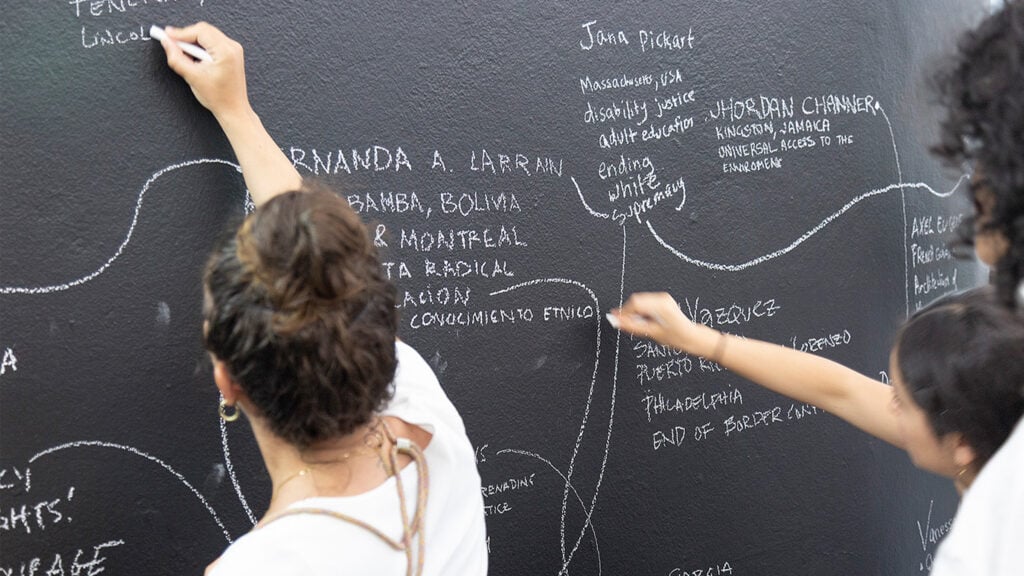

WAI Architecture Think Tank Approaches Practice as Pedagogy

Nathalie Frankowski and Cruz García use their practice to help dismantle oppressive systems, forge resistance spaces, and reimagine collective futures.