April 25, 2014

Learning From Mao: USC Students Redesign a Fashion Classic

Students from the USC School of Architecture were given a strange task: create a Mao jacket out of unconventional materials.

Lee Schuyler Olvera, Associate Professor in Practice at the USC School of Architecture wants his fifth-year students to go beyond their comfort zones. His studio, “Truth in Making, Craft: An Architectural Inquiry,” unfolds along a series of exercises intended to help students explore process, materials, and space in new, tactile ways. The semester progresses from object making (“Reliquary”) to the production of a garment/habitable object (“Mao Jacket”) and finally to habitable space (“Shroud”), shifting scales from the table-top, to the body, and then to dwelling.

I recently visited Olvera at his campus office. Surrounded by models, shelves spilling over with materials, and drawings, we spoke about one of the more intriguing elements of the studio, the Mao jacket project, and what it means in the bigger picture of architectural education and practice.

Guy Horton: First thing’s first—why a Mao jacket? It’s very iconic, of course, but what’s the significance here?

Lee Schuyler Olvera: There were conversations about using other types of uniforms, like lab coats, but the students kept coming back to the Mao jacket. A number of students are from China so for them there was a sort of humor or irony in it. I think it resonated because it carries a lot of political and cultural baggage. The Mao jacket is the second of a trio of projects. The first one, Reliquary, has students follow what they are good at, making an object of beauty out of materials they are comfortable with so they have confidence in the outcome. They know it will turn out good. The Mao jacket is intentionally opposite this.

GH: So you build them up and then break them down.

LSO: [laughs] Yes, I suppose so. They have no idea how it will turn out and they aren’t allowed to use the obvious material, which is fabric. They can use anything but fabric.

The ghost of Mao: Calvin Lee crafted his jacket out of crocheted electronics wire.

Courtesy Sean Miller

GH: This seems to take them into new territory. Can you talk about how this plugs into contemporary notions of architectural pedagogy?

LSO: I see it as material research. Students pick a material and they aren’t allowed to change their minds. It’s absolutely about architecture but it pushes the boundaries and forces them to come out from behind representation.

GH: Were there any moments when students had to completely rethink what they were doing?

LSO: Many. Everybody encounters problems at some point. I’ve seen some spectacular failures. It forces them to work in a different way. The hand and brain have to work together. Call it generative detailing. It’s easy to create beautiful renderings, but this is not that. They have to do something real, a willful act.

Nicholas Tedesco’s jacket is made of 12,244 pencil erasers, which he sourced from a school supply company at a price of $250

Courtesy Elliott Lavi

GH: What is your interest in the exploration of materials?

LSO: USC has a number of studios that take on the issue of materiality. There’s a lot of design-build going on. As a school we want to be at the forefront of making and materiality. To me doing architecture or art is always about craft. I come from a drawing background where things build up over time. It’s iterative and it takes time to do really good work. Same with the offices I’ve worked in. I want the students to feel dissatisfied with contemporary practice, with what they know.

GH: You mean you want them to feel dissatisfaction with the status quo in architecture?

LSO: Yes. In other words, don’t be satisfied with just doing things mechanically or fitting in. Architecture is about crafted materiality and space. I want the students to get a sense of being creative makers and designers, not just technicians. The jacket, like architectural space, has to perform. It can’t be sculpture. It’s a setting for things to happen.

Student Ellio Lavi adds last-minute touches to his Mao jacket, which was fabricated out of vinyl tubing and fishing wire.

Courtesy Elliott Lavi

GH: So how much time are we talking about?

LSO: Probably something close to 2,000 hours. It’s a lot of hours, but it shows they can stick with something and work through it. If you can do this you are probably going to be good at solving complex architectural or environmental problems.

GH: What would your Mao jacket be made of and what would it look like?

LSO: [laughs] I get asked this question all the time so I know the answer. I would make it out of rubber, like old tires. It would be around for a million years. You give it new life. You would think you could use recycled rubber to clothe everybody on the planet.

GH: [laughs] Now that you have chosen rubber, you aren’t allowed to change your mind. Your students would appreciate this.

LSO: Yes, they would.

Approximately 13,000 thumbtacks—held together by industrial-strength caulk—comprise Sean Miller’s jacket.

Courtesy Sean Miller

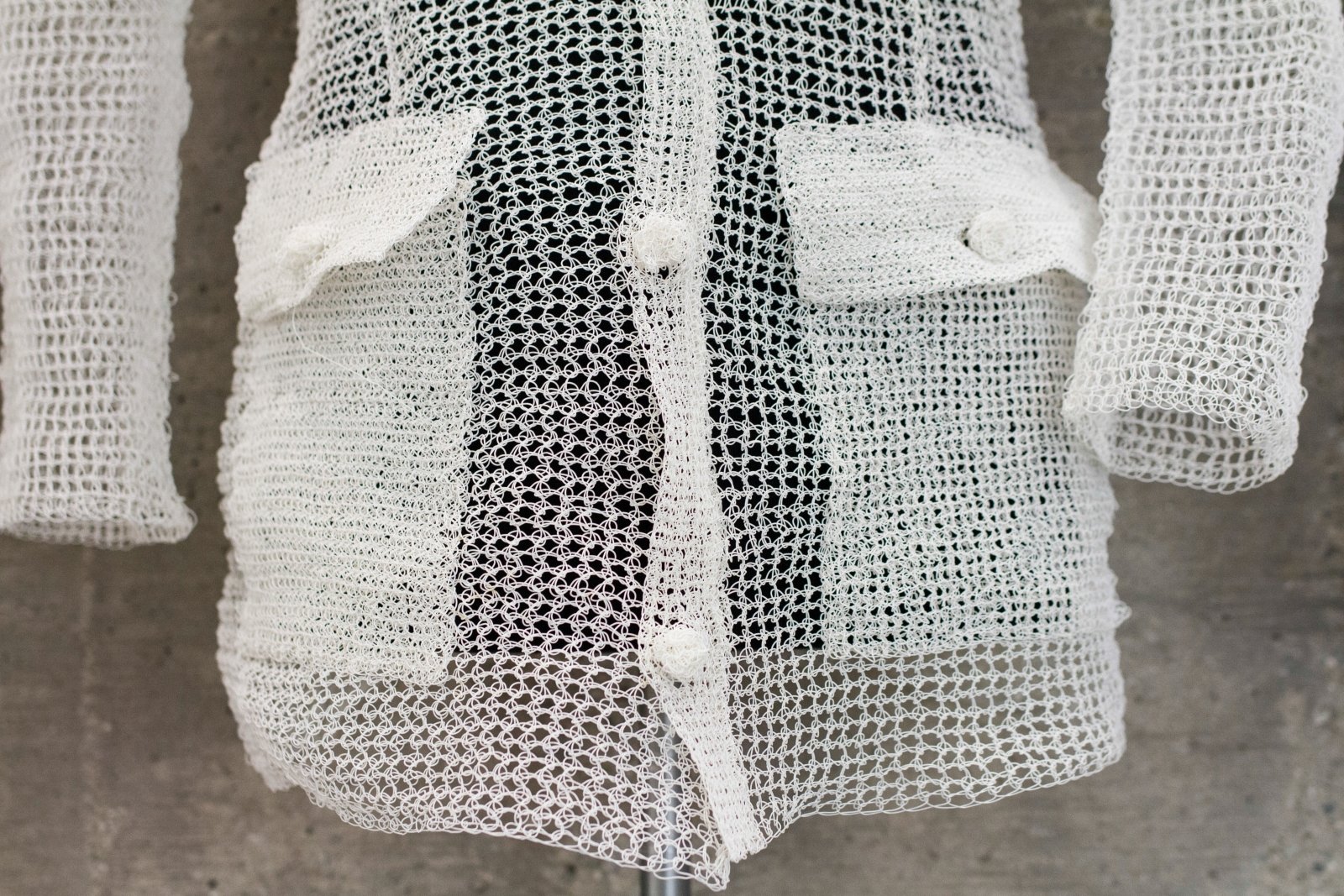

Left: Lee’s transparent jacket; Right: A jacket designed by student Yimeng Wang, who ordered 5,500 Mao pins from China to assemble her coat.

Courtesy Elliott Lavi

GH: What has been the experience of the studio so far? What do you hear from students?

LSO: Well, it’s the last studio of their undergraduate career and by this time they are really ready to make something. They end up valuing the experience and are grateful that they can do something unexpected. It leaves a lasting impression. I’ve been doing this studio for three years now and I hear back from former students who have shown this work as part of their portfolios at job interviews for some big firms, and they say this project is always a hit and generates a lot of interest.

GH: In an age of the digital, where design is frequently driven by software and technology, this seems to be taking it back to the level of the hand-made, to craft, as you say. Is this an intentional move away from the computer or perhaps a different way of blending hand, eye, body, and machine?

LSO: This doesn’t exclude technology. It’s just another tool. But I think it goes back to making discoveries by engaging materials, by making something that has to perform. It has to be wearable, in the end. I question this idea of going back to the hand. I see it as moving forward with the hand.