January 27, 2010

Letter from Baltimore: A New (Art) Hybrid

In her monthly “Letter from Baltimore,” Elizabeth Evitts Dickinson writes about architecture, culture, and urbanism in a city more often associated with violent crime than with good design. Click here to read her previous posts. For more by Dickinson, visit her blog, Urban Palimpsest.On January 16, Baltimore’s Contemporary Museum kicked off its 20th year in […]

In her monthly “Letter from Baltimore,” Elizabeth Evitts Dickinson writes about architecture, culture, and urbanism in a city more often associated with violent crime than with good design. Click here to read her previous posts. For more by Dickinson, visit her blog, Urban Palimpsest.

On January 16, Baltimore’s Contemporary Museum kicked off its 20th year in the city with a winter party celebrating both its anniversary and its latest exhibition, Participation Nation: Art Invites Input. Entering the packed gallery that evening, I was confronted with an incredible noise. Not the usual din of opening-night gallery chatter, but raw, hard sounds created by a couple of well-dressed guests toying with what looked to be the control panels of a radio production booth.

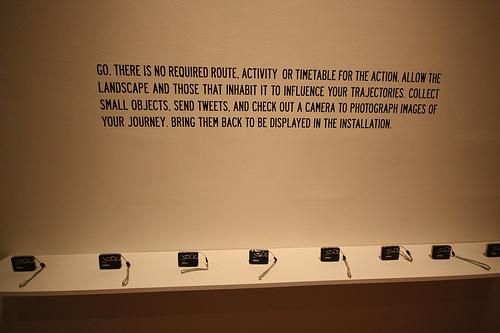

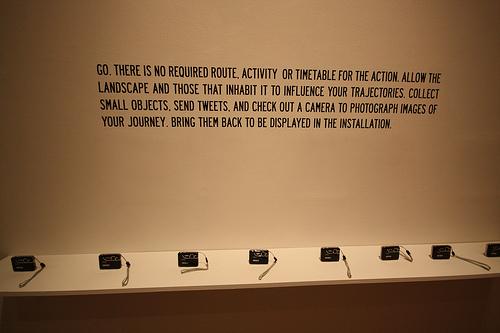

Nearby, brand-new digital cameras were perched on a single shelf, with an invitation to take one. Across the room, a series of photos rotated through a projector; the fuzzy close-ups, oddly cropped street scenes, and neat rows of buildings resembled the kind of amateur city snapshots that clutter my own camera disc. To the left of this projection, a nearly empty set of shelves mounted to the wall held a few scattered items—a Gatorade bottle, a vintage kitchen appliance, candy wrappers.

Participation Nation is the first in a series of 20 exhibitions that will run over the next 18 months at the Contemporary. In honor of the museum’s anniversary, Irene Hofmann, its curator and executive director, invited 20 people from the institution’s past to select one artist whom they believe represents the future of contemporary art. From that list, Hofmann put together small group shows.

The remarkable thing about this first art exhibition is the lack of, well, art. With the exception of a small gallery of works by the artist Lee Mingwei, the installation is primarily an infrastructure created to invite the visitor in. Those digital cameras are courtesy of Finishing School, a Los Angeles–based collective that examines “issues such as individual rights and freedoms, governmental power, scientific exploration, and corporate branding and influence using humor, technology, and activism to explore the city and contribute to the collective work.”

Here, they want you to take the cameras out into your neighborhood, snap away, and return a full memory card to the museum. The images will then be loaded into the slide show. The empty wall of shelves is meant to house the physical stuff that you might find along the way—trash, treasure, whatever. As it grows in content, it becomes a kind of shrine to the ephemera of urban life.

As for the electronics setup at the entrance to the show, it is the work of the arts collective Neighborhood Public Radio. NPR invites artists, activists, musicians, and community members to create original programming that they then stream via the Internet or using low-power portable FM transmitters. In addition to the table of pre-made sound synthesizers that the audience can play with in the gallery, NPR will run a workshop on how to assemble a small FM transmitter. It is also hosting a coast-to-coast audio project where individuals are invited to dial in noises via cell phone. Every Saturday, NPR broadcasts a mashup of those sounds. Click the play button below to hear a transmission from earlier this month.

.

When the Contemporary was founded two decades ago, it was a “museum without walls,” a roving gallery that staged exhibitions throughout the city. Today, the museum has a permanent space and it is the art itself that has begun to roam. Since Hofmann took over curatorial duties in 2006, she has staged shows that engage artists in the community and that use the city as inspiration. “For me, the most memorable and successful projects with the most lasting impact have been those where an artist has spent time in Baltimore, made work with people here, and, in the case of this show, invited everyone to participate in the piece,” Hofmann says.

What’s so compelling about the artists that Hofmann taps (and the ones that these guest curators selected as the “future of contemporary art”) is that they often blur the line between artist and designer. Hofmann introduced Baltimore to the work of Fritz Haeg when he came to town two years ago to transform a front yard into a garden. She brought in the design/arts collective Future Farmers and developed group shows like 2008’s Cottage Industry, which saw artists setting up site-specific ventures in available storefronts throughout Baltimore. All engage the city in direct and immediate ways and many include individuals who straddle the art, activism, and design fields.

The Contemporary Museum’s curator and executive director, Irene Hofmann, poses with the members of Finishing School.

The Contemporary Museum’s curator and executive director, Irene Hofmann, poses with the members of Finishing School.

So what is it that’s drawing a new breed of contemporary artists to not only examine the urban environment, but to also explore ways to incite change? And how do we qualify them? Are they Designer? Artist? Architect? Activist? All of the above?

Hofmann believes these contemporary artists “represent a hybrid.” And she’s thinking “not only of individuals like Fritz, who are both trained as an architect and an artist,” she says, “but groups like Future Farmers, where among them you have artists, educators, graphic designers, and programmers.”

“Many of these artists live and have been witness to such different kinds of urban conditions,” she adds. “This is one of the points of activism for this generation. Whereas activism [in art] in the eighties was around HIV and AIDS, it was around feminism, now it shifts to these other pressing issues. We now see a different kind of activism that gets blended into their practice.”

Hofmann says these types of boundary-blurring exhibitions will continue. They make sense for a city like Baltimore, where many residents are preoccupied with the state of their surroundings, yet feel somewhat impotent to effect change through traditional channels. “Here, you’re picking up hypodermic needles outside of your museum. It’s the kind of place and city where the needs are much more urgent,” Hofmann says.

Participation Nation runs through April.