March 19, 2010

Letter from Baltimore: The Humanitarian-Design Debate

In her monthly “Letter from Baltimore,” Elizabeth Evitts Dickinson writes about architecture, culture, and urbanism in a city more often associated with violent crime than with good design. Click here to read her previous posts. For more by Dickinson, visit her blog, Urban Palimpsest.Photo: Emily PillotonNothing—not even well-intentioned design—is above reproach. The confluence of organizations […]

In her monthly “Letter from Baltimore,” Elizabeth Evitts Dickinson writes about architecture, culture, and urbanism in a city more often associated with violent crime than with good design. Click here to read her previous posts. For more by Dickinson, visit her blog, Urban Palimpsest.

Photo: Emily Pilloton

Nothing—not even well-intentioned design—is above reproach. The confluence of organizations and individuals working to bring design practice to those who might not normally get it seems to have hit a critical mass, and with it comes the inevitable backlash. In an entry written last fall on his Design Altruism Project Web site, David Stairs lit a firestorm of debate when he argued that “social networking has struck the design world with the force of the Indonesian tsunami bringing changes of sorts, but no guarantees of lasting change.”

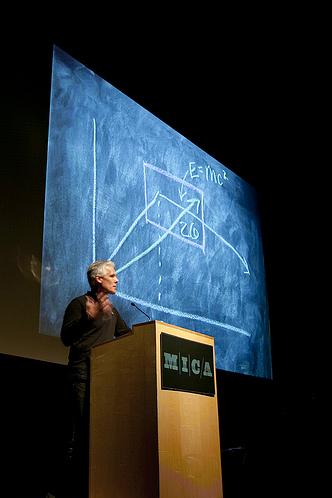

So what do we mean by humanitarian design and is it really making an impact? I thought it a stellar time to gather some of those who work in the trenches to discuss that question, and the opportunity arose last week when Emily Pilloton came through Baltimore with her Design Revolution Road Show. Pilloton and the Project H architect Matt Miller parked their Airstream trailer on the campus of the Maryland Institute College of Art (MICA) for a few hours and participated in a panel discussion with John Bielenberg, the founder of Project M, and Julie Lasky, the editor of Change Observer. (The panel was hosted by MICA’s Center for Design Thinking and co-sponsored by D:center Baltimore and Urbanite magazine.)

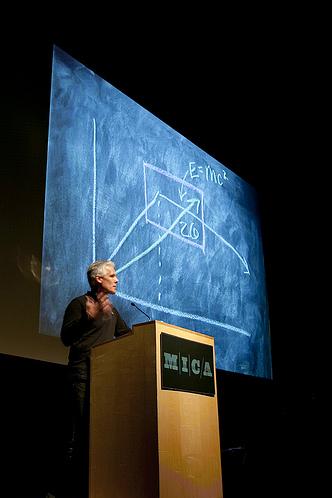

Bielenberg presented a slide show before the panel discussion. Photo: Marian Glebes

Bielenberg presented a slide show before the panel discussion. Photo: Marian Glebes

Pilloton and Miller told the crowd that humanitarian design is fundamentally about action. They derided the trend of “green drinks,” where design professionals gather to chat over cocktails and talk about changing the world. Miller called design without action “masturbation.” They outlined their plans to move from San Francisco to Bertie County, North Carolina, to create a design-build program at a local school.

This raised interesting questions about how designers engage with community. Do they need to live there or is it OK to pop in? Last fall, I wrote a blog post about a Project M initiative in Detroit and it provoked a strong reaction from commenters. The debate centered around the value of designers coming into a community for a short period of time versus setting down roots and staying for the long haul. Bielenberg played a clip from a Detroit Fox affiliate that showed the community response to the simple project that the designers realized during their time in Detroit:

(Can’t view the clip? Try watching it on myFoxDetroit.com.)

Afterward, the Baltimore architect Eric Leshinsky said that he thought the clip made a valuable point. “It’s such an easy target for people who think ‘social design’ should have deeper consequences than horseshoes or that people who parachute into a situation are not entitled to help change a situation,” Leshinksy said. “It’s case by case, and totally reliant on the interactions between the people involved. That project would never have happened if the Project M participants and neighborhood folks did not have attitudes that allowed for dialogue and common language.”

Meanwhile, Julie Lasky, the former editor of the now-defunct I.D. magazine and the editor of the new Change Observer, discussed her decision to leave print, join the world of the Web, and report on the social-design movement. Never one to shy away from a critical debate, Lasky invited David Stairs and Valerie Casey, the founder of Designers Accord, to dialogue about the value of social design on her site. The result is a heated argument between two passionate designers. (Lasky said the two emerged from the process with a new respect for each others’ views.)

Beneath this conversation of—to quote Bielenberg—“design for the greater good” was the undercurrent of funding and structure for today’s design practice. When you engage directly with the community, and that community likely cannot afford your services, the traditional client-designer relationship implodes. Now there is frequently the midwife of the foundation, the grant, or the patron, causing designers to reconsider their traditional business plans. Lasky’s Web site has a Rockefeller Foundation grant that is due to expire at the end of this year, forcing her to become both an editor and a fundraiser (a position that is perhaps only slightly different from having to support ad sales at a print publication.) Both Project H and Project M have taken to the Web to raise money using emerging fundraising sites like Kickstarter.

Hearing about the enormous response to the designers’ programs, and seeing the depth and breadth of projects coming in from all over the world on Change Observer, it became evident that humanitarian design is more than just a passing, fashionable trend. How it will evolve and shape the future of design and design practice, though, is still very much up for debate.

.

Related: Watch Emily Pilloton’s January appearance on the Colbert Report. Read more about her book, Design Revolution: 100 Products That Empower People.