March 8, 2013

Lighting in Public Spaces Should Animate, and not Just Illuminate, the Dark

Using light not only to illuminate, but to animate the dark

Courtesy Lynn Saville

If I could write about something for more than four lines that didn’t have to be set to music, I’d write about my old friend fear. —Bill Withers

The sun has set. I leave my house. I close the door. I am outside in public. It is nighttime. The pavement is where I left it this morning. The trees are in place. The building is still standing. Yet I have entered into an entirely different kingdom. Same place + different time of the day = different world.

It’s after dark. I see my world differently. I act differently. Now a new set of rules governs my behavior and that of everyone around me. My brain is on high alert and in a nervous dialogue with itself. At night we step into an environment where—in an evolutionary sense—we’re not supposed to be.

As a species, we have less-than-stellar vision in the dark; we can’t see detail or color. We lack all the basics that nocturnal species have. That is, we don’t glow like cephalopods, nor do we have eyes that enhance and collect light like cats. As a lighting designer and environmental psychologist, I know better than to fear the dark in my own neighborhood. But like everyone else, I have read the studies on rape and crime. As a woman I know that I’m statistically in more danger from a relative or acquaintance than from a random attacker in the park. Reports show that a young man of color is far more likely than I to be a victim of nighttime assault, and that most after-dark crime happens to people living in poor communities. Yet I still feel cautious, wary, and a bit unsettled as I walk down my safe, well-lit street.

In the city, strangers are everywhere—people to whom we’re not related, people we don’t know, people who inhabit a totally different cultural space from ours. In the daytime, this isn’t a big deal. Then we make countless small judgments, nearly imperceptible, about whom to walk next to and whom to avoid. But at night, under the glow of the moon or streetlights, we strain and peer at each other. Who looks interesting? Who might be dangerous? We may feel an excitement and glee at being out at night—the joy of after-dark social life.

But we may also feel our “old friend fear.” The word fear actually encompasses a complex group of feelings. Yi-Fu-Tuan, in his wonderful book Landscapes of Fear, identifies two clearly distinguishable types: alarm and anxiety. Alarm is triggered when we perceive a looming threat. Alarm kicks off our primal need to fight or flee. Anxiety, on the other hand, is a diffuse sense of dread, a presentiment of danger when nothing in the immediate surroundings can be pinpointed as hazardous. When anxious, we are in a watchful, anticipatory state. A memory, smell, news report or change in the environment can activate anxiety.

Our own vivid imaginations can make us anxious, as can an unfamiliar place. Anxiety can arise when we expect something other than what actually happens. The depth and persistence of our anxious feelings are deeply personal matters. Nevertheless, we expect lighting to minimize our anxiety when we are out in the night.

Illustration by Charlie Brokate

Lighting in the public sphere usually performs multiple functions, addressing a variety of emotional states. At one level, it assists our survival alarm. We want to see the potential threat of a car, drunken vagrant, sidewalk crack, open manhole, or person who intends harm. Lighting allows us to perceive the danger and avoid it. Light makes decision and action possible.

Recently, I visited a housing project that suffers from deep poverty and attendant crime. They brought me in to light an outdoor stairway that had been decorated by children in a local arts program. The project seemed straightforward: illuminate the steps to make them more visible, and feature their aesthetic qualities. But the local police pointed out that darkness at the top of the stairs concealed gang members waiting to accost anyone climbing up.

To avoid leading residents into danger, we needed to put a light at the top of the stairs, to help secure people’s actual physical safety. Public lighting can also act as a kind of social treatment for our diffuse anxiety and dread. This is by no means trivial. In fact, it’s one of lighting’s most important functions.

We live in a complex and bewildering world. We are constantly exposed to reports of violent and alarming attacks that—however far removed from our time and place—can leave us shaken and fearful. We feel threatened even when we cannot see the threat. In my experience, this feeling of anxiety can precipitate a demand for more light.

A few years ago, a university where a young woman was assaulted on campus asked my advice. With students and parents clamoring for “more light!” I was taken aback to learn that the attack happened in a dorm room, after a date. No amount of campus lighting would be able to help her or anyone in this kind of situation. The real task was to add lighting that would help assuage the heightened anxiety women now experienced walking on campus at night.

Typical security lighting, with its harsh glare, would actually escalate feelings of apprehension. Instead, the light needed to engender pleasant feelings. As crime rates drop in many urban areas, I’m increasingly asked to replace existing security fixtures with lighting that is bright enough for safety but also attractive and enchanting.

The Battery Bosque, NYC: garden design by Piet Oudolf, architect WXY Architecture, landscape architect The Saratoga Associates, client NYC Parks & Recreation Dept. and The Battery Conservancy, lighting Tillett Lighting Design,

Courtesy Carrie Snyder

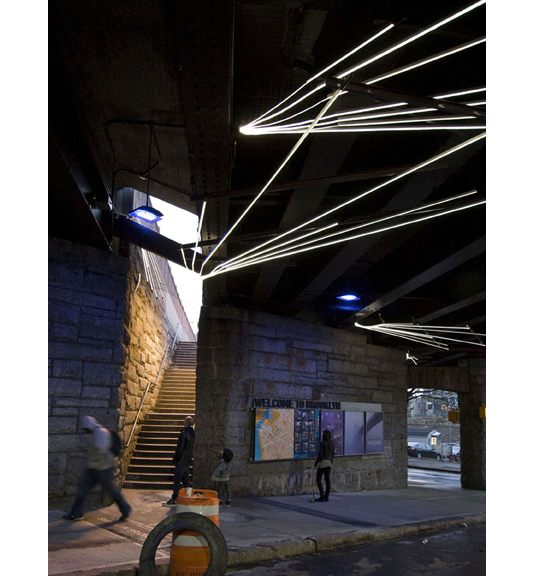

This Way, Brooklyn Bridge underpass art installation: artists Linnaea Tillett & Karin Tehve; lead design consultant Emphas!s Design; commissioned by City of N Y Department of Transportation, Percent for Art Program, and DUMBO Business Improvement District

Courtesy Seth Ely

Public lighting is a balancing act between what is actually happening at night and the feelings that float through human awareness. Let’s seek to engage the interplay between psychological states—the whisper of fear, unease, or even delight—and the realities of the communities into which it is being introduced.

If we use light not simply to illuminate, but animate the dark, to help create social space at night, we can achieve more safety for more people without using larger and larger quantities of light. With so many species in danger from excessive human-generated light levels, not to mention the urgent need to dramatically reduce our electrical consumption, it is particularly important that we learn the skill of walking this particular tightrope.

Linnaea Tillett, Ph.D., IESNA, is an environmental psychologist and lighting designer. She is principal of Tillett Lighting, lighting consultants for waterfront landscapes, infrastructure, parks, public art and private interiors.