June 24, 2013

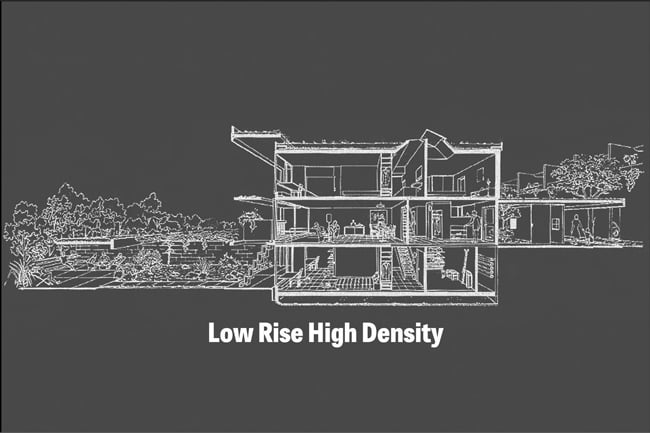

New York’s Forgotten Experiment in Low-Rise High-Density Housing

What can past solutions teach us about solving today’s housing crisis?

1968, the year that famously whispered of revolution was also an optimistic one for reform in New York City. A housing scarcity, prompted by urban migration, a building slump, and an aging building stock demanded the attention—and the dollars—of both a state and city governments a moment of relative political progressiveness. The New York State Urban Development Corporation opened its offices with its standards set to, what was at the time, “the highest ambitions of twentieth century development.” Among mandates like housing for the poor, middle-income, and elderly, the UDC set out to build low-rise high-density communities. During its seven year run the organization facilitated an unprecedented bedfellowing of academics, aesthete architects, museum curators, and city officials in a plan to design and build affordable public housing.

Turn the clock forward 40 years or so. As real estate prices in New York City continue their climb and prompt new experiments in alternative housing—from Bloomberg-touted, space-compromised micro-units to new alliances in mixed-income public/private development—a small show at the Center for Architecture looks back on Low Rise High Density housing, the moment of its emergence, and its baring on how we face housing crises today.

The show is an archival feat. Much of its materials—quotational wall text, video interviews, detailed plan and section drawings—is culled from oral histories its curator Karen Kubey began five years ago as a Columbia graduate student. Interested in a housing typology that, she says, had been elemental in the architectural education of her professors, but was unknown her and her design peers, Kubey set off to Switzerland. Following what had once been an architectural pilgrimage of sorts, she traveled to Siedlung Halen the famed low-rise high-density development hemmed by a riverbank outside Bern. In interviews with Atelier 5, the project’s architects, Kubey draws out the stories of its creation and the ripple effects of the typology. Anecdotes about the party-proof thickness of walls, or the cultivation of an urbane attitude outside the zoning codes and land prices of the city give the little show a fitting intimacy.

Atelier 5, Siedlung Halen, Bern, Switzerland, 1955-61. Section.

Drawing by Atelier 5 Architects

Halen is a lovely work of Modernism. Its concrete façade, swathed in evergreens, is enchanting—a kind of European counterpart to a tropical brutalism. The béton brut is strong and elegant, and alternate height units and floor-to-ceiling windows allow for a dense linking of light-filled private spaces. Young architects of the time, like Richard Rogers, Kenneth Frampton, and Peter Eisenman, flocked to it. For one reason, low-rise, high-density offered an answer to the mounting problems of suburbia, combining the common sense benefits of density, like public transportation and commercial amenities, with the desire for individual space, common areas, and one’s own front door.

In the 1970s, as suburbs began to reach their limits architects were imagining a host of alternatives to urban growth. “These are all projects where the architect is making an obvious choice [to build low-rise high-density],” Kubey explained. Detailed plans, sections, and site plans articulate the obvious choices of the designers, and provide continuity between display panels, which progress chronologically from Siedlung Halen to Marcus Garvey Village in Brownsville, Brooklyn, and then contemporary examples.

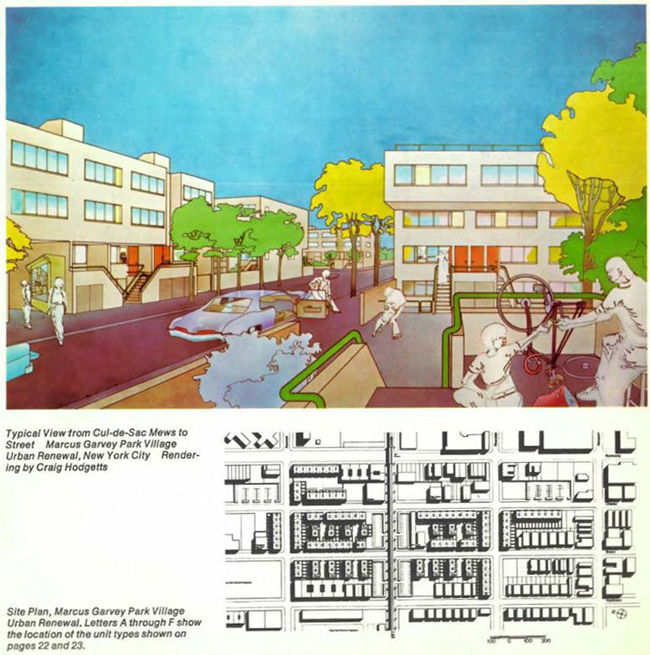

Marcus Garvey Village, the other historical pillar of the show, is a low-rise high-density public housing project designed by Kenneth Frampton in consultation with the Institute for Architecture and Urban Studies. The building is many things Siedlung Halen is not: highly urban, inhabited by low-income families in a disinvested neighborhood, and poorly maintained. These conditions aside, it supports more density than its surrounding public housing high-rises while offering courtyard spaces, stoops, and mews.

From the catalog for Another Chance for Housing Low-Rise Alternatives, Museum of Modern Art, Craig Hodgetts and IAUS.

Intended as the first project in a program of urban renewal spearheaded by the UDC, Garvey’s architects were known to sleep in the building after its opening to investigate its progress. MoMA, under the direction of Arthur Drexler, launched an exhibition into the typology concurrent with its opening, called, “Another Chance for Housing: Low Rise Alternatives.” But the seventies were tough financially for New York State, and Nixon cut funding to the UDC, halting the housing plan. What’s been left is a community with some issues, but as Kubey points out, to blame the architecture would be to overlook the years of disinvestment that has lead to high crime rate in the neighborhood, and the private management that neglects the property.

It was an anomalous moment in the history of architecture to be sure. Jonathan Kirshenfeld, an architect and director of the Institute for Public Architecture that Kubey directs and sponsors the show, put it this way: “Who would have thought Peter Eisenman, the most abstract man on the planet, would have started the Institute for Architecture and Urban Studies with social housing?” In 1976, the year the project was completed the IAUS was an avant-garde intellectual think tank, but surprisingly its leaders saw themselves launching their practices with public housing.

That didn’t happen, so the question stands: What does this mean for architecture today? Bringing together work of the past 40 years, from a striking sun bleached Alvaro Siza to west coast developments like Swan’s Market in Oakland by Pyatok Architects, what Kubey calls the “catch-all” panels of the show’s last wall chronicle the reach and continued relevance of a perhaps neglected form of housing. It’s a lot of material packed into a tight space, not given nearly extensive treatment that Siedlung Halen and Marcus Garvey receive.

Pyatok Architects, Inc., Swan’s Marketplace, Oakland, CA, 2000. Courtyard.

Courtesy Karen Kubey

While the center’s library is an apt location for the archive-based material, cleverly incorporated into its shelves, there is less room for large drawings and photographs. But as a launching point the material makes its point, and augmented series of talks by low-rise high-density architects and academics could merit a future life in publication.

In recent years shows, like Making Room organized by the Architectural League of New York and MoMA’s Foreclosed, demonstrate that housing still demands consideration and retooling. The suburban lifestyle that architects were imagining in the 1970s their way out of, has now, without a doubt crashed. And while “density” and “urbanization” have more cache than ever, how to accommodate people is a perennial problem. Smaller units and shared space, like the ones floated in the Making Room competition, is one option. New Yorkers in particular have already carved up space and opened their homes; a cruise of craigslist is evidence of that.

Foreclosed as well as the show Rising Currents, are proof of MoMA’s desire to take a speculative, instead of purely retrospective, view of architecture and its contexts. MoMA PS1, in the expansive if vaguely defined Expo 1, makes gestures towards a discussion of public space.

Some developments, like Via Verde in South Bronx, are working towards models of affordability through publicly subsidized, mixed-income buildings capitalizing on design as a critical amenity. But the housing question is forever an open one.

On June 26, the exhibition’s final program will turn to the importance of low rise high density now. As Kirshenfeld said, the show is one of advocacy, advancing the questions of public architecture through discussion and research.

Caitlin Blanchfield is a writer, editor, and curator living in New York City.