January 10, 2023

Office for Political Innovation’s Reggio School Treats Structure and System as Pedagogy

The school is designed according to the principles of the Reggio Emilia Approach, an educational model developed by Italian educator Loris Malaguzzi that seeks to empower children as the primary agents of their education. “The role of the architecture is to become an opportunity for collective self-experimentation as a source of learning and teaching by experience,” explains Jaque. “The design of the school accumulates many different architectural traditions to allow for kids growing to acknowledge experience and feel how they are part of larger ecosystems and societies.”

The result is not so much an individual building, but an accretion of towns and villages—replete with a skyline of pitched gables and sun-drenched loggias—centered on a vegetated public square, or agora. Classrooms as assembled according to ascending age groups, the youngest students are located on the first two floors, with a greater rootedness in the surrounding terrain, while the oldest students are placed at canopy-level of the vegetated courtyard. Cork is the primary exterior element of the project, and, with its yellowish-brown complexion and uneven surfacing resembles something of a wattle-and-daub half-timber structure, spare for significant moments of bare concrete, porthole-like windows, and triangular panes of glass blending into the window wall facade system. Cork for the project was sourced from Extramadura, in Spain, and Alentejo, in Portugal, and it doubly serves as exterior cladding and the primary form of thermal insulation. The material also happens to be exceptionally sustainable; the bark of the Cork Oak tree is harvested every five to ten years, leaving the tree intact for future cultivation.

That same emphasis on sustainability is translated to the relatively austere interior of school—concrete is not hidden behind wall paneling and the like, and the mechanical systems are laid bare to the building occupants. For the latter, approximately 70 percent of the energy consumed for heating and water is sourced from a rooftop solar array. At the agora, an approximately 120-foot-long window operates automatically to control the internal climate. All such features, and their visibility, is a key component to the school’s mission. “I would read it as a naked building to a large extent, because the mechanical systems and the structures are basically part of the pedagogy,” says Jaque. “The performance and daily life of the building becomes a big source of the learning opportunities that kids are exposed to.”

Would you like to comment on this article? Send your thoughts to: [email protected]

Latest

Products

How to Specify Stone Sustainably

Essential considerations and resources for selecting stone that meets environmental standards without compromising design.

Viewpoints

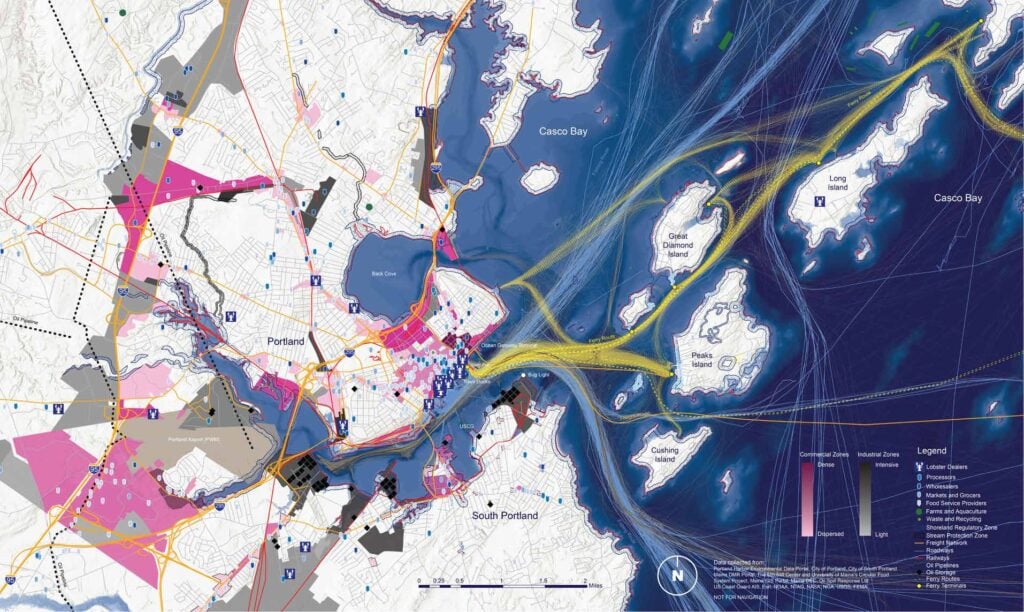

Envision Resilience Participants Design for Vulnerable Coastlines

The annual studio, now in its fourth year, brings together students from various universities to envision adaptable futures for coastlines in the Northeast United States.

Projects

Studio De Zwarte Hond Reimagines Dutch University with Circular Renovation

The Herta Mohr building showcases how resourceful reuse can transform a legacy structure into a sustainability paradigm.