October 1, 2013

Parsons Dean on Creating Curriculums of Choice

Parsons the New School for Design’s multidisciplinary curriculum evolves with the twenty-first century.

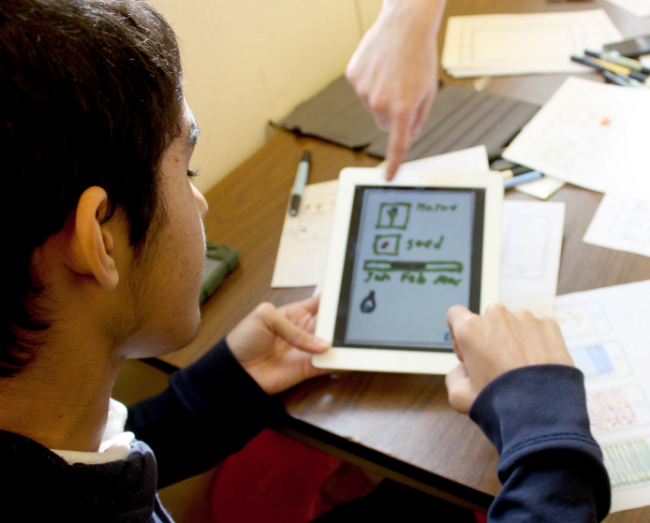

This year Parsons formed a partnership with New York City’s Center for Social Innovation to incubate design-led social innovation projects by Parsons students and alumni. One of the projects in development is Citysteading, a community-driven process for empowering and engaging marginal-ized communities.

Courtesy Josh Barndt, Alexandra Castillo Kesper, Braden Crooks, Aubrey Murdock, Joel Stein, Charles Wirene

Every generation is presented with challenges specific to its time and place. We live in a world changing in ways that were unimaginable at the beginning of the Industrial Revolution, when design education first began to take shape. Technology (aided and abetted by design), advances in scientific knowledge, and shifts in social and cultural norms shaped design in the twentieth century. Our problems today involve more complex and interconnected systems—climate, cities, resources, networks, flows—and call for a new paradigm. Design in the twenty-first century is of critical importance in both addressing these challenges and transforming them into opportunities to remake the world around us. To do so, design education must change.

Design schools have traditionally adhered to a model that builds programs based on a foundation year, a well-defined and contained introduction to the basics of material, form, and color. And while that foundation is an important cornerstone of design education, it leaves little room for the more exploratory methods of cross-disciplinary and technology-based learning, and for understanding and applying design in the context of the larger world. That old model needs to evolve to reflect design’s enhanced role as a catalyst for innovation and creativity.

Almost a decade ago at Parsons, we began reevaluating our academic programs to respond to this new context. Over the past several years we have introduced a number of graduate programs that educate designers for this era, from Transdisciplinary Design,to Design and Urban Ecologies, which explores the complex forces that influence urban growth and development. And now, this fall, our incoming freshmen are the first to take part in a redesigned undergraduate curriculum that provides greater opportunities for self-directed learning, cross-disciplinary collaboration, and exposure to academic areas beyond the traditional boundaries of art and design.

The new Parsons curriculum is about choice. Students today absorb information constantly from a variety of media and sources. The process of learning has become so multi-directional that it requires purposeful navigation. The proliferation of massive open online classes (MOOCs) and open courseware has created unprecedented opportunities for the self-directed learner and introduced a radical and productive disruption to educational models throughout the world. Online learning, however—at least for those who pursue it toward a formal degree—still operates on the model of assembling courses within the narrow context of a subject area. This assumes that knowledge can be gained or downloaded as discrete units (courses) and pieced together upon completion. Design education requires more curation and context. If the goal is to facilitate an experience that helps students define who and what they might become as designers, then we must provide vehicles that allow them to veer off traditional pathways of learning.

The Parsons DESIS Lab (Design for Social Innovation and Sustainability) spent a year immersed in the New York City neighborhoods of Greenpoint and Williamsburg, Brooklyn, uncovering ways to improve the city.

Courtesy Ben Ferrari

So from day one, Parsons students are actively considering what is compelling to them about design, and they are empowered to make decisions that shape their education. Our course requirements are still defined (and the result of many years of development), but within these parameters students are presented with possibilities. We continue to teach the fundamentals of drawing, making, technology, and critical thinking, but those skills are integrated across four years of study rather than organized into discrete courses. This structure encourages students to push the boundaries of disciplinary learning beyond the routine questions of fashion vs. architecture vs. graphic design, and into the larger issue of design’s potential as an agent of change. This will require them to understand the relationship between design and society. They might, for example, explore ideas of authenticity and memory, attempt to understand time as a form of composition, and work with space and materials as they relate to the human form and cultural objects.

In addition to promoting choice as a key element of the experience, the changes to our curriculum place significant emphasis on integrating studio learning with the liberal arts. Every student takes two sets of paired courses in their first year—a design studio integrated with a liberal arts seminar—that are intended to generate unexpected connections between the two classroom approaches. In the seminar, they explore concepts through critical analysis, presentation, reading, and writing—and in the studio they apply them through research, prototyping, and creative process. Students in these Integrative Studio and Seminar courses are able to select a thematic lens through which to approach the course material, choosing from such options as Avatar, Memory, Community Engagement, and Visual Culture. (These types of thematic options are also made available to them in their required studio courses: Drawing/Imaging, Space/Materiality, and Time).

Across the Parsons curriculum we have ensured that disciplinary learning will not preclude more exploratory studies—that students will be the ones deciding whether to dive deep into their majors or further expand their coursework. To that end, we established that every program will include, at minimum, enough free space for students to pursue a minor in addition to fulfilling their degree requirements. This minor could be in another design or humanities discipline, or in an area such as entrepreneurship and new economies.

Hello Compost, a thesis project by Parsons alumni Aly Blenkin and Luke Keller, seeks to introduce food-waste collection to low-income families by giving them a percentage of the revenue, which will earn them credits for purchasing locally grown produce.

Courtesy Aly Blenkin and Luke Keller

Being part of a university, the New School, opens up remarkable possibilities for cross-disciplinary study. As our incoming freshmen progress through the curriculum, we expect to see them using the flexibility afforded them to do the unexpected. That might mean an architecture student minoring in politics, a fashion major pursuing a course of study in Chinese, or a communication designer taking a minor in psychology. Or it might mean fine arts students collaborating with jazz students, or management students initiating a project with philosophy majors. We don’t know what they will choose to do, but we’ve opened the doors for them. It will be up to each student to exercise that freedom and create an experience that appeals to her imagination and goals.

But no matter what course of study a student pursues, she will not learn about design in isolation. Today’s complexities require approaches that interweave design with other ways of thinking and doing. Students need to actively engage with the role design can play in shaping the world around them, and gain real experience working with others across disciplines, cultures, and perspectives. This approach drives the work of consultancies such as IDEO and Frog Design, where social scientists, designers, artists, and business professionals collaborate, applying their collective expertise. At Parsons, we teach similarly cross-disciplinary routes, taking advantage of our unique position within a university that values design as equally as it does the social sciences, performing arts, management, policy, and liberal arts. This environment provides natural opportunities to bring together students and faculty from a diverse array of academic fields, to conduct research, tackle real-world projects, or just share ideas. When I see the results of these cross-university efforts—whether it’s the design and construction of passive houses or a program for youth that connects education to design and social change—I’m more convinced than ever that design education cannot operate alone.

Empowerhouse was Parsons’s entry into the U.S. Department of Energy’s Solar Decathlon. Students and faculty partnered with Habitat for Humanity and the local government to make their competition entry the first passive house in Washington, D.C.

Courtesy Martin Seck

Rethinking design education required us to approach curriculum development with the same creativity, flexibility, and exploration that we encourage of our students. It also forced us to ask some fundamental questions: How could we accommodate increased breadth without sacrificing depth? Give students more opportunity to explore the urban environment without compromising academic rigor? Provide a flexible array of choices while still guiding them toward a consistent set of learning outcomes? Answering these questions and developing solutions necessitated a different strategy, with faculty from all areas of the school playing a role. Taking our cue from open-source sharing and crowd-sourced information gathering, we’ve made the curriculum a constant point of communication, hosting workshops and forums, and creating shared virtual libraries of instructional resources, readings, and syllabi. It’s an iterative, ongoing process; we call it designing the design school.

This is a crucial time for design education. The issues of our time require that designers focus their talents not just on form and function—the principal obsession of the previous century—but on the interconnections between design and society, and the potential of design as a transformative force. The world has changed; the role of design has changed. And the way that designers are taught to engage with the world must change, too.