April 9, 2025

The Shenzhen Energy Ring Sets a New Standard for Circular Infrastructure

When one thinks of a recycling facility or energy plant, they most likely picture nondescript building blocks and unsightly smoke stacks unceremoniously strewn along the fringes of a major city or taking up substantial space within its center. Masterfully converted into the Tate Modern art museum during the mid 1990s by Herzog & De Meuron, London’s Battersea Power Station has long dominated the capital’s riverbank. Luckily, the monumental structure was designed to be as little of an eye soar as possible: a restraint articulation of the still ornamental Art Deco style popular at the time of it was erected.

As was evident in the complex that preceded the Shenzhen Energy Ring—a brand new waste-to-energy plant challenging tradition—this level of considered intervention is rarely carried out. Meeting the bottom-line, industrial architecture tends to favor cookie-cutter efficiency over the more nuanced implementation of idiosyncratic site-responsivity and adaptability. But as cultural and environmental expectations continue to shift, outdated conventions go out of the window. Regardless of what some might think of the Bjarke Ingels Group-designed CopenHill facility in central Copenhagen—an imposing edifice replete with a sloped roof moonlighting as a ‘urban ski piste’—it represents a paradigm shift in how these types of necessary buildings are being programmed. Why not introduce a second function or, as is the case with the Shenzhen Energy Ring, ensure that such a facility integrates into its surroundings, becoming visible as a vital learning resource.

“When designing the facility, we were solving an existing problem while also aiming to make a long-term impact on our climate crisis,” says Chris Hardie, Design Director of Perkins&Will subsidiary Schmidt Hammer Lassen (SHL)’s Shanghai office. According to the World Bank, humans produce 2 billion tons of municipal solid waste each year. Much of it goes into landfills which account for 19% of global methane emissions. In a city with as explosive a population growth as Shenzhen, China, the dilemma is ever present. “The intent of the architecture was to deal with the complexity of the power plant’s process and express it in a simple clear form, elevating an otherwise mundane building type into something more iconic, impactful, and decipherable,” he adds. “To fully address the problem, there also needed to be an element of education.”

Sustainability embedded in the Construction of the Energy Plant

‘Co-authored’ with Gottlieb Paludan Architects, the 2-million square-foot structure was imagined as a monolithic yet tapered “drum”—evoking the undulating hills in its immediate vicinity—that nestles into its valley-like site without the need for extensive excavation. Completed at the end of 2023, the singular structure rises an impressive 196 feet at its pinnacle with its 3280-wide (1 km) circumference room descending to 131 feet at its other end. Even if a few technical outbuildings line its perimeter—the volume is just large enough to contain all of the necessary elements.

“Early on, we determined that the internal equipment wouldn’t change but that the building didn’t necessarily need to have walls in the traditional sense,” Hardie explains. “Not having them would actually help with getting rid of the heat produced during the processing of the waste, something that normally requires additional energy to mitigate.” Ultimately, however, it was determined that some degree of enclosure was necessary to maintain security and keep out inclement weather. A more permeable ventilated facade would be the right compromise.

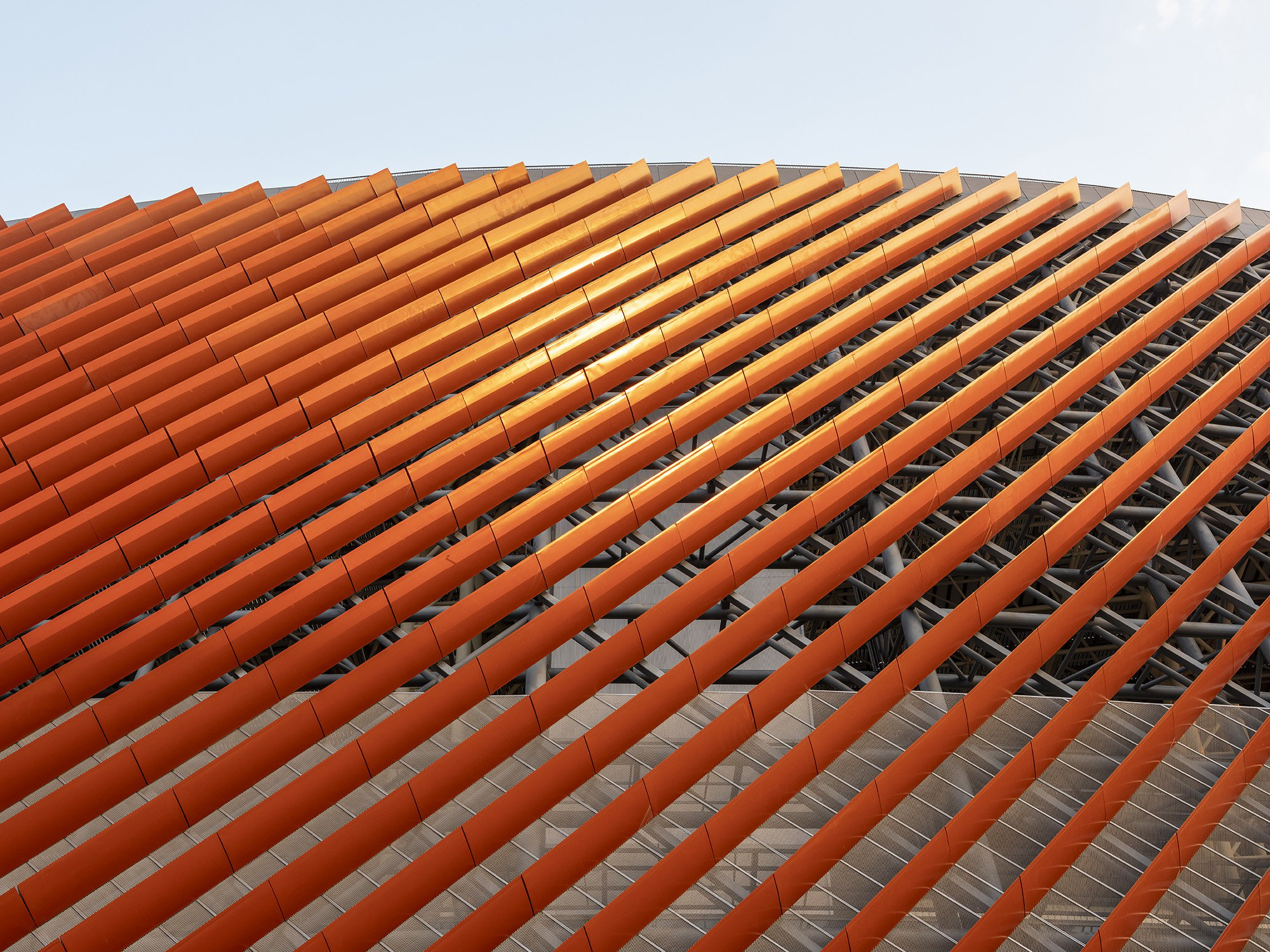

“The lamella design principle for this component enabled us to create a simple and continuously conical figure, while still allowing all the necessary technical functions to penetrate the outer skin,” says Thomas Bonde-Hansen, Gottlieb Paludan Architects Design Director.

Adding to Shenzhen Energy Circle’s reduced ecological footprint and eventual LEED Gold status—one of the first industrial buildings in China to receive this ranking—are the 8215 modular triangular unitized-lamellas that wrap the structure’s exterior. “They were limited to 13 feet in length and so it was quite easy for smaller trucks to transport them to the site,” Hardie explains. “This process also only required two workers for assembly. Most of the structural elements were prefabricated which helped with bringing down the embodied carbon.” A steel louver system on the roof provides additional natural ventilation, smoke exhaust, and daylighting.

A Striking Burnt Orange Facade

Each of the individual facade components were coated in a striking burnt orange-toned coating. “Initially, the client wanted the facility to be slightly more hidden but for us that wasn’t the point,” Hardie explains. “The choice of color was important to make sure that city dwellers living nearby would know the building was there. Ultimately the goal is to make people aware that this is happening and that there is a reason and the reason is that we’re all making too much trash, so we need to do something about it.”

As one of five sites part of a newly organized Eco Tourism route running through Shenzhen, the Energy Circle is open to the public through a robust education and interpretative program. Comprehensive tours take approximately two hours. The collaborating firms also made sure to encircle the structure with both soft and hard scaping, essentially turning a good portion of the site into a park.

Facility’s Design Meets Functionality

Extending the site responsive and multi-functional approach is the green roof walking path, not dissimilar that which tops the previously mentioned CopenHill, but reserves to employees and other officials. The rest of this expansive canopy is outfitted with photovoltaic panels, imbuing the Shenzhen Energy Ring with yet another function. All together, the net-zero facility processes a whopping 5,000 tons of domestic waste a day and in turn, generates 1.13 billion kilowatts of electricity.

“There’s one, perhaps strange, aspect of the project: that it’s actually meant to render itself obsolete, not just by turning waste into power but by also educating the wider public about the problem and suggesting better practices,” Hardie concludes. “So if they’re really successful in that endeavor at some point in the future, there might not be a need for something as large as this.” Because of the way the Shenzhen Energy Circle was designed, it could very well take on a different function when that time comes or even more extreme, be disassembled with the various modular components of its construction repurposed into something entirely different.

Would you like to comment on this article? Send your thoughts to: [email protected]

Latest

Profiles

Zoha Tasneem Centers Empathy and Ecology

The Parsons MFA interior design graduate has created an “amphibian interior” that responds to rising sea levels and their impacts on coastal communities.

Viewpoints

How Can We Design Buildings to Heal, Not Harm?

Jason McLennan—regenerative design pioneer and chief sustainability officer at Perkins&Will—on creating buildings that restore, replenish, and revive the natural world.