October 21, 2013

Photographing New York: New Book Documents Life in Bloomberg’s NYC

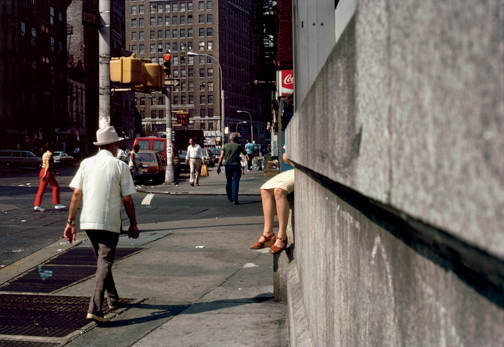

When photographer Robert Herman humanized the concrete jungle

In a few months Mayor Bloomberg will be leaving office, ending an era that radically changed New York City, starting with Rudy Giuliani. Some say that during that time, the city lost its oomph, that they miss the edgy side of the city wiped away by new upscale condos and chain stores. Others cheer the better quality of life. They cite the bike paths and smoking bans; they don’t miss the filthy streets and hold-ups on every corner. For sure it was a different New York and everyone who lived through those times has an opinion. Photographer Robert Herman expresses his own point of view with his camera. His new book, The New Yorkers, from Proof Positive Press, is an inspired photo essay that pays homage to the city that was and to its denizens.

Herman’s lush, colorful photos show us just how far the Manhattan of today has changed in the ensuing years. He reminds us that, not too long ago, a ride on the subway was to submit one’s self to trains covered in graffiti, not of the artistic kind but of the sad, empty vandalism sort. A time when you could still find vacant lots in SoHo and when Little Italy was a neighborhood of hard working Italian-Americans.

Perhaps Herman’s greatest gift is the way he’s able to connect the city to its inhabitants and vice-versa – the characters and their places in it. He finds all the right niches where individuals somehow take possession of “their “ spots in city, softening and humanizing the concrete jungle. New York was tough then, but as he shows us, the rough streets were also somehow welcoming of personal expression.

Having seen the Edward Hopper show (recently closed) at the Whitney, it was not difficult to observe parallels between how the two artists looked at architecture and people’s interactions with it. Both were great observers; they knew their subjects well and sensed how people physically relate to space, be this indoors or outside. They saw where and how people fit in. Hopper would study the buildings, the light, and the perspective in sketches (masterpieces in themselves) until he knew he got it right. And then he applied the same care to “people” the canvas.

Herman, who lived downtown, was in constant contact with his subject matter, in place and ready when just the right light hit that right corner. “I try to walk where there is direct sunlight and avoid the shadows of the midtown canyons. So, I stay downtown, in Tribeca, Soho, and the Lower Eastside,” he told me when we talked about his work. “In my street photography, direct sunlight makes for stronger pictures!”

He uses that sunlight to illuminate the poetic moments he sees in his cast of city characters, from young to old, from eccentric to the lonesome. He is able to do this because in observing them he understands how they relate to where they are, whether at a desk, a doorstep, a park bench or waiting for the subway. He has the grasp of that most essential aspect of architecture – how people relate and react to space.

“My beginnings were rough, challenging, and I felt vulnerable. This helped me to identify with others who I perceived were vulnerable in some way as well” he says. With this sensibility Herman’s shutter was able to capture how individuals living at the margins of society could somehow fit in the larger whole.

Herman admits that now it’s much safer to live in the city. At same time he tells me he misses the “the funkiness: the small businesses that have been pushed out and replaced by corporate chains.”

About the never-ending proliferation of condos and widespread gentrification he says, “It is much more difficult for the middle class and artists to live in Manhattan. As a result, the city becomes a little duller; a great deal of the quirky individuality of the people and the neighborhoods is rapidly disappearing.”

We don’t know what more “progress” will bring our idiosyncratic Gotham, but thanks to Herman’s work we can for sure have a renewed appreciation for a time when, in spite of its harshness, the city was also a gritty stage where all of its inhabitants could find their place in the sun.

All photos Courtesy Robert Herman

Paul Clemence is an award-winning photographer whose work is part of many collections, including the Mies van der Rohe Archives and housed by MoMA, New York. He exhibits both in the U.S. and on the international fine art circuit, from classic B & W prints to large scale photo installations. A published author, his work can also be seen in major design and lifestyle publications. His “Architecture Photography” Facebook page receives over half a million hits monthly.