October 9, 2013

Prentice Women’s Hospital Succumbs to “Progress”

Chicago’s Prentice Women’s Hospital succumbs to “progress”

Courtesy C. William Brubaker © via Flickr user UIC Digital Collections

Hospital buildings, with their high standards of hygiene and efficiency, are a restrictive brief for architects, who all too often end up designing uninspiring corridors of patient rooms constructed from a limited palette of materials. However, this was not the case in Bertrand Goldberg’s 1975 Prentice Women’s Hospital. The hospital is the best example of a series of Goldberg-designed medical facilities, which all adhere to a similar form: a tower containing rooms for patient care, placed atop a rectilinear plinth containing the hospital’s other functions.

Goldberg’s approach was to let the interior requirements of the building define the exterior form, which gave rise to the peculiar plinth-and-tower form of his hospitals. The lower floors contained surgical suites, research laboratories, dining facilities and maintenance areas. Because future developments in medical technology may require spaces to be changed dramatically, Goldberg chose the form of a rectilinear plinth, which provides the greatest possible flexibility. On the other hand, since the role of a hospital (accommodating and caring for patients) was unlikely to change, Goldberg felt the building’s tower need not be flexible. Here, Goldberg was inspired by anthropologists such as Edward T Hall, who were developing theories of human interaction in different spatial orientations.

Courtesy Landmark Illinois

The ‘four leaf clover’ plan of this tower splits each floor into four tiny communities, fostering greater social ties between the neighboring occupants. The radial arrangement creates a large number of crisscrossing routes around each floor, meaning there is more chance for incidental social encounters than in a typical hospital with rooms arranged along a corridor. It also places all patients roughly equidistant from the centrally-located nurses’ station, allowing for efficient care.

Courtesy Landmark Illinois

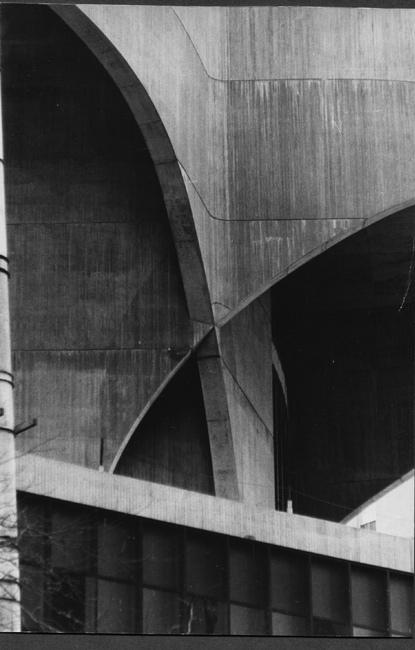

With the exterior form determined by this interior layout, and requiring external load bearing walls, most structural solutions of the time would have required columns supporting the structure. However, by taking the radical approach of employing software developed by the aeronautics industry (some 20 years before Frank Gehry made this tactic famous), it was possible to cantilever these structural walls from the central core of the building. This is a structural solution which, according to Goldberg’s son Geoffrey Goldberg, is not found anywhere else in the world.

With its focus on human relationships and building community, its striking concrete form, and its use of the most modern structural solution available at the time, the Prentice Women’s Hospital (as well as Bertrand Goldberg’s work as a whole) brings together a number of streams of architecture from the early 70s, touching on Brutalism, the humanism of architects such as Aldo Van Eyck, and the Metabolist movement dominated by Japanese architects such as Kenzo Tange and Fumihiko Maki.

Courtesy © Flickr user seanbirm

Sadly, the importance of this building and its singular combination of architectural influences was not enough to guarantee its place in the ever-changing streets of Chicago. Despite efforts of dozens of architects, and even a last-ditch proposal from Jeanne Gang and The New York Times’ Michael Kimmelman, the owners, Northwestern University, demolished the building in the summer of 2013, claiming it could not meet the needs for a cutting-edge biomedical research facility they have planned for the site.

A version of this article original appeared on ArchDaily.