July 28, 2012

Q&A: Susan Chin on Urban Farms

In New York City, where more than 8 million of us live in very close proximity to hundreds of our immediate neighbors, many of us are also near some form of urban agriculture. Today there are ten times more urban farms in Gotham than in San Francisco and Seattle. And urban farming is growing in […]

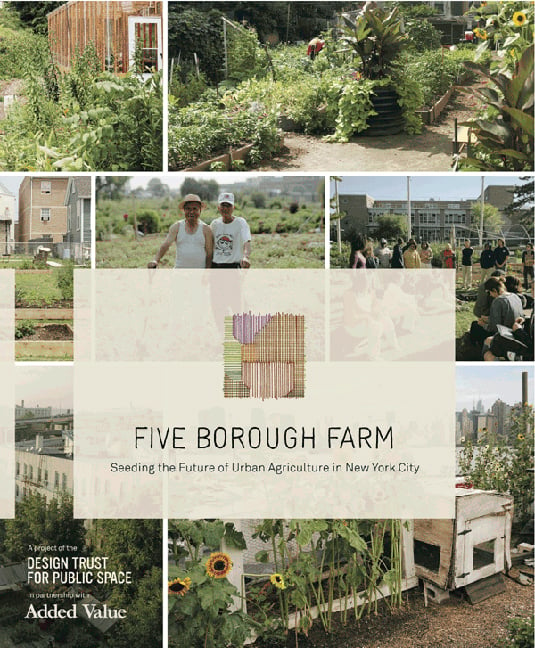

In New York City, where more than 8 million of us live in very close proximity to hundreds of our immediate neighbors, many of us are also near some form of urban agriculture. Today there are ten times more urban farms in Gotham than in San Francisco and Seattle. And urban farming is growing in every one of our five boroughs. To document this fact of our city’s life, the Design Trust for Public Space, a non-profit organization, released its groundbreaking study: Five Borough Farm: Seeding the Future of Urban Agriculture in New York. The website and the book launched recently. To get an insight into this healthy urban development, I asked Susan Chin, FAIA and executive director of the Trust to answer a few questions about the culture, the realities, and potential for the urban farming movement.

Susan S. Szenasy: This week you launched the Design Trust’s research, website, and book, Five Borough Farm: Seeding the Future of Urban Agriculture in New York City. It’s quite an accomplishment. Can you talk about what got you to this milestone?

Susan Chin: Added Value, a community organization in Red Hook, had the foresight in 2009 to apply to Design Trust to work on an urban agriculture project. We partnered with them to bring on a team of Project Fellows, including experts in policy, public health, and sustainable design, a graphic designer and photographer. The team documented the many kinds of urban agriculture activity taking place today in New York City and interviewed more than 100 key stakeholders–farmers and gardeners, government officials, funders, and support organizations–about their goals, needs, challenges, and opportunities.

Along the way we learned that urban agriculture is about much more than food. It’s about teaching kids where carrots come from, providing leadership skills and job-training to high-school students, capturing storm water and food waste for compost, and bringing neighbors together to transform underutilized land into vibrant public space. All of these activities contribute to health, social, economic, and ecological benefits that align with many municipal goals and programs.

We also found that many urban agriculture stakeholders were looking for ways to understand and articulate the impact of their work. For example, New York’s farmers and gardeners want to know, “How do my summer youth education programs influence the 60 kids who participate?” City officials want to know, “What’s the potential for food production, for job creation?” So we created the nation’s first metrics framework–we’ve recommended dozens of ways that people can start to track their activity (food production, pounds of food waste collected, ages of youth participating in programs, sales at farmers market). We’ve also launched an online tool that will be beta tested and aggregate data across many farms and gardens citywide to inform urban agriculture policy; we plan to make this available next year to anyone who wants to use it.

SSS: It surprised me to learn that New York City is the national leader in urban ag, surpassing San Francisco and Seattle, North American cities I would associate with eco-conscious, healthy lifestyles (including fresh produce, freshly picked). Is this flowering of urban farming a fortuitous byproduct of the recession, which brought about a dramatic slowdown in construction? Or is it more complex than that?

SC: There are many factors. First, today’s urban agriculture boom is rooted in New York City’s past. Most of the City’s urban agriculture activity is concentrated in low-income neighborhoods. These areas suffered widespread housing abandonment and disinvestment in the 1970s. Local residents began reclaiming city-owned vacant lots and turning them into gardens and productive landscapes. Consequently support organizations and government partners such as Green Guerillas and GreenThumb formed to foster this community-based stewardship. City government developed a mechanism to make this city-owned land available. That’s the foundation for today’s urban agriculture movement.

There are other factors as well. New York City’s zoning, for instance, permits urban agriculture virtually everywhere. As a dense city, New York City is a hub for the entrepreneurs who are leading urban agriculture. One commercial farmer we interviewed told us: “New York City is not at all the most likely candidate for urban agriculture at all in my mind…what’s really interesting and unique is that New York City is a city full of entrepreneurs and people who make smart connections.”

SSS: I understand that we now have some 700 food-producing farms and gardens in NYC located in such previously unused places as rooftops, schoolyards, vacant lots, and plots adjacent to public housing. Is this a result of squatting or is there some enlightened land use policy at work here?

SC: On the one hand, there’s incredible grassroots initiative–New Yorkers have managed to turn every possible neglected and underutilized site into farms and gardens. We know how to squeeze a lot out of small spaces! At the same time, municipal policy is generally supportive, but not coordinated by any one agency. For instance, Mayor Bloomberg’s Grow to Learn initiative is expanding more than 100 food-producing school gardens citywide. New York City Housing Authority staff supports 245 food-producing gardens on public housing grounds. Mayor Bloomberg’s PlaNYC, City Council Speaker Christine Quinn’s FoodWorks, and Manhattan Borough President Scott Stringer’s FoodNYC, support expanding urban agriculture citywide.

New York City could do more to coordinate its efforts and build off of existing programs. Right now, more than a dozen City agencies are involved with urban agriculture in some way, but none of them consider urban agriculture a core part of their mission. So they often lack the resources or authority to address urban agriculture, to incorporate it into existing, or potentially complementary plans and programs.

Five Borough Farm provides City officials with a roadmap to support and expand urban agriculture citywide, including more than 30 policy recommendations to coordinate actions across agencies, leverage existing investment, and increase resources to urban agriculture, such as land, soil, compost and funding.

SSS: In a city known for its high real estate values, can urban farming survive once the banks start financing construction? What needs to be put in place, today while the slowdown persists, to protect and help grow our city farms?

SC: Typically farms and gardens are not competing with developers for land. Urban agriculture takes very little space–many community gardens are about the size of 3 subway cars, and there are smaller projects that grow food. Rooftop farms don’t have this conflict at all.

That said, we very much want to see urban agriculture become a more permanent part of the city’s landscape and governance. We recommend three ways to make this happen:

– Establish an interagency urban agriculture task force. This would bring City officials together with farmers and gardeners to share information about their work, and generate strategies to support and expand urban agriculture citywide

– Develop a citywide urban agriculture plan to guide land use and resource allocation. This would help specify where new farms and gardens should be located, determine appropriate agency budgets needed to support this activity, and engage a wide range of urban agriculture stakeholders through a public planning process.

– Assess the suitability of city-owned land for food production. There are more than 14,000 city-owned listed in the city’s official online database. Figuring out how to evaluate these parcels, and working with City agencies to identify and make them available for urban agriculture is one of our goals for the coming year.

Brooklyn Grange, Photo by Cyrus Dowlatshahi

SSS: I hear that our progressive, health- and environmentally-conscious mayor is not promoting urban ag. What would you like him to recognize about the importance of this resource to our city and its people?

SC: Although the first version of PlaNYC didn’t mention urban agriculture, the updated version specifically states the City’s support for urban agriculture and even establishes some benchmarks for expanding. What we’ve done in Five Borough Farm is provide a roadmap for how that could happen. For instance, there are more than 600 stalled development sites in the five boroughs. The City could incentivize developers to establish temporary farms and gardens on those sites, such as Riverpark Farm on FDR Drive and 29th Street, which is supplying a nearby restaurant with fresh produce grown in about 3,400 milk crates that can be easily moved when construction starts up again.

SSS: Many of our best restaurants use local produce. Thinking about restaurants reminds me that there could a robust composting program for organic waste in the city. And healthy soil is hard to come by in this asphalt jungle of ours. These and other challenges need to be met and solved if our farming sector is to survive and thrive. What needs to happen, on a policy level as well as a consumer level, for the Five Borough Farm to be a vital and sustainable reality?

SC: Making and replenishing soil is essential to farming and gardening. A director of one of the City’s botanical gardens noted, “If I had $10 to spend on plants and soil, I’d spend $1 on plants and $9 on soil.” On a policy level, composting our organic waste makes sense. The City can reduce costs associated with exporting it to out-of-state of landfills and replenish our farms and gardens as well as parks. The Sanitation Department is already looking at ways to maximize its compost operations; we hope to work with them to figure out ways to make this resource available to farmers and gardeners citywide.

I mentioned earlier that farms and gardens are concentrated in low-income neighborhoods; these are also places hardest hit by the recession. Many programs already exist specifically to support urban agriculture in these neighborhoods, but more could be done. We found there are significant race- and class-based disparities within NYC’s urban agriculture community. We need to ensure that everyone has equal access to resources and information, and that farmers and gardeners have the opportunity to build their capacity to fund raise, to collect data on programs, and to influence policy. That will go a long way towards making urban agriculture fully sustainable for future generations.