October 30, 2013

Sanctuary Shelter Project: Providing Refuge for Battered Women in South Africa

Providing sanctuary and shelter for battered women

Gender-based violence is among the most prevalent and ignored violations of human rights. The physical and emotional harm caused by human predators infects households, communities, and cities across the globe. Social marginalization and dismissive government exasperate these problems. This is reflected by the rising occurrence of crimes against women in many countries the world over. The United Nations estimate that acts of violence against women affect at least one out of every three women globally (1).

The statistics in South Africa are grim. Although it is estimated that only one in nine rapes are reported, the country still stands as having the highest rate of reported rapes per capita in the world (2). Ill-equipped medical facilities, untrained clinicians, long wait times, and the daunting threat of social stigmatization deter battered women from seeking immediate physical or post-traumatic treatment.

Furthermore, criminal statistics show that 73% of women know their attacker, 40% of all incidents occur within the victim’s home, and an additional 20% occur within two blocks of their own homes are at the home of a friend or relative (3).

As architects we must address this condition with the creation of safer spaces. In doing so, we can design new treatment space, rethink the way we design domestic space, attract women to seek proper healthcare treatment, and foster preventative conditions at home and in the neighborhood.

Sanctuary Shelter Project

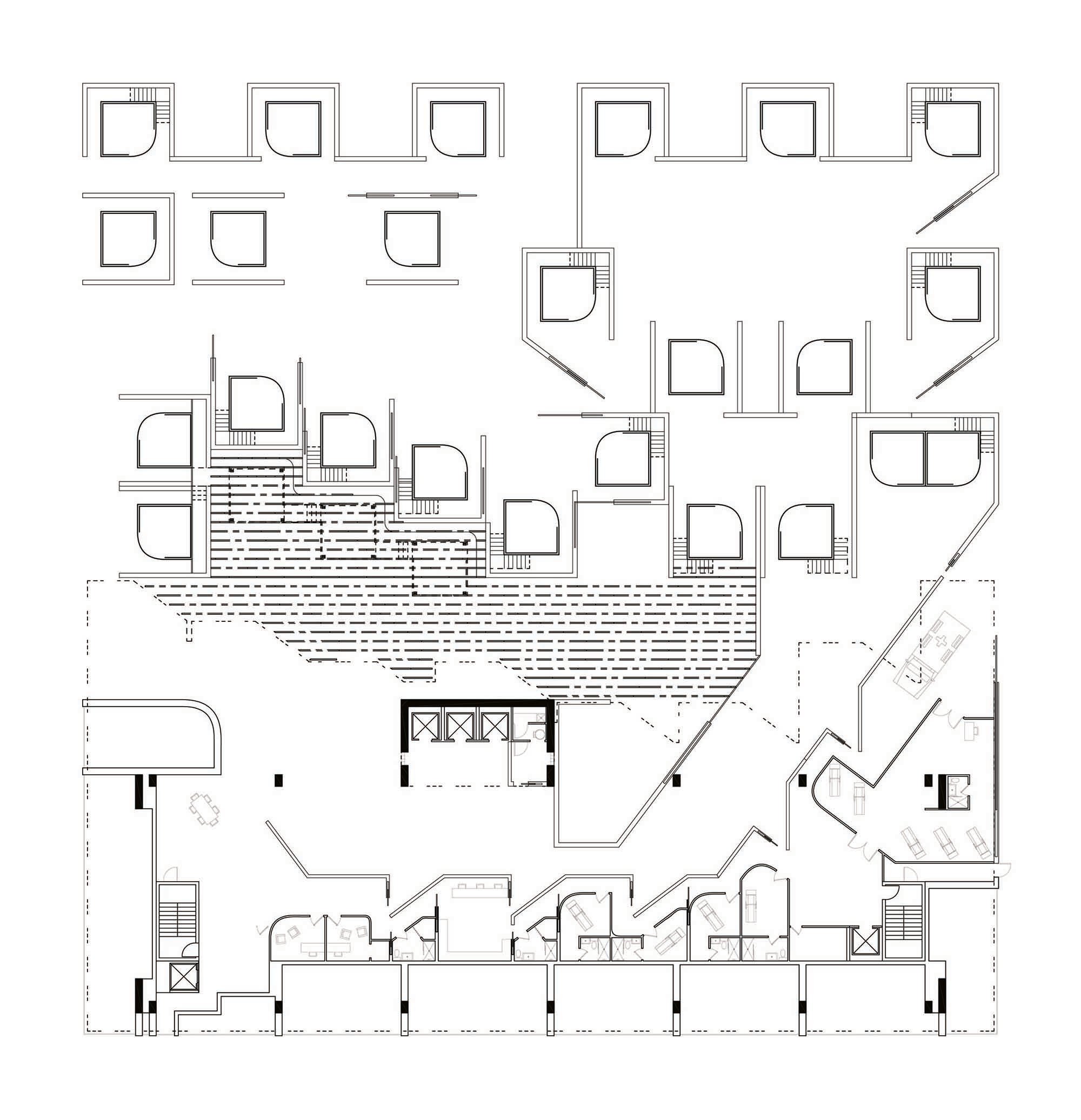

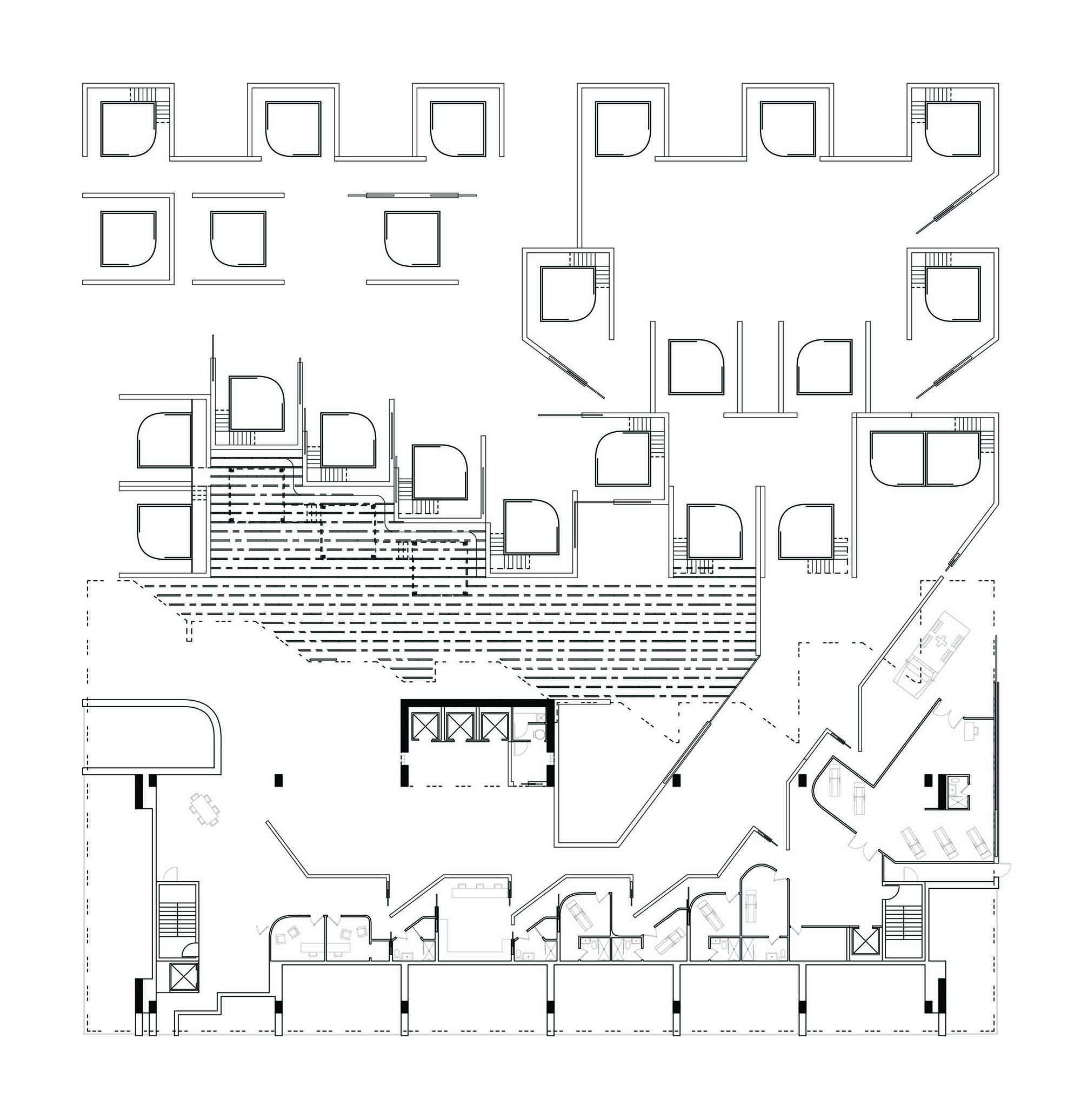

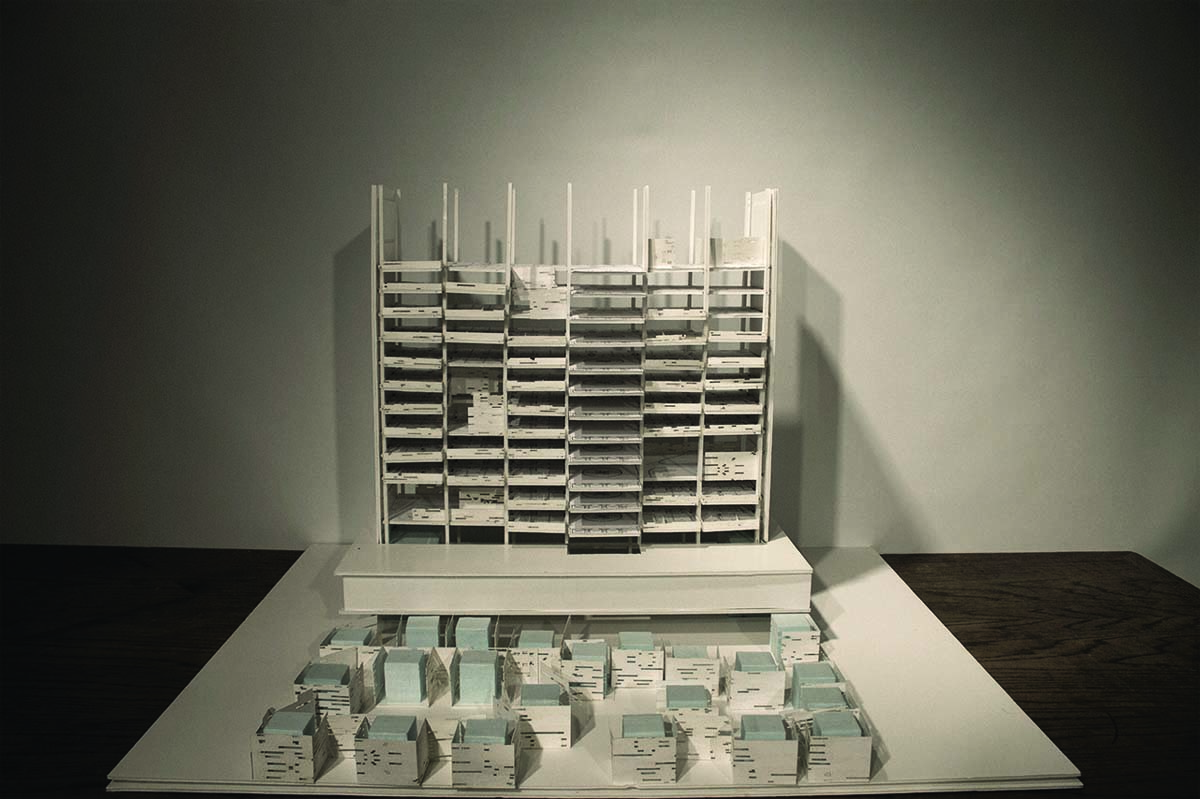

Today there is tension in South Africa between secure ‘underground’ women shelters and women-empowerment organizations. My project hypothesizes that within the blighted urban conditions of Johannesburg, a new typology must emerge: secure sanctuary environments which provide spaces for women to heal in solitude, while also creating outlets for communal growth and foster solidarity among women. The project intends to operate on a two-tier programmatic strategy, providing immediate shelter and medical care to women along with more permanent housing for them.

Courtesy Mia Zinni

In order to secure the facilities, along with creating an environment that feels safe for its users, the architecture implements methods of camouflage, through materiality and hidden fenestration. Situated in the heart of Hillbrow, a notoriously dangerous neighborhood with a high density of housing, the project is in an ideal location to serve the community. The surrounding market and network of vendors around the site are already populated with stands operated by women, and have the potential to act as its own grassroots security system. The market could provide the women residing in the shelter with outlets for work. The stores and vendors can blend easily into the existing urban fabric, camouflaging the inner facilities.

Courtesy Mia Zinni

To understand the role of architecture in ending violence against women within Hillbrow, my design methodology asks how we can have a positive and proactive role in creating “safe” spaces:

–How can architecture create secure sanctuary environments for affected women to heal in? In addition, how can it create outlets for communal growth, fostering solidarity among women?

–What impact can camouflaging architecture have on secure women’s shelters, clinics or houses?

–How can gradients and quality of light impact the psychological feeling of being safe within a space?

–Where can high-activity neighborhoods be utilized to foster proletarian neighborhood-watch security networks?

–How can facilities be secured without becoming prison-like enclaves?

–Where can the architecture create introspective regions for individual healing and active areas to foster communal activity?

Designed to be an extension of the existing market around the site, a new market, in front of the proposed retrofit-tower is to be programmed as a camouflaging space, as well as an outlet for women to be reintroduced into the community, providing them economic support and promoting community stakeholdership. The market thus becomes a security system where women own and operate the stalls, simultaneously acting as security guards, monitoring those who have access to the shelter. The underground network of paths allows direct access up into the market stalls from the retrofitted tower-shelter apartments units. The sanctuary spaces at the heart of the building are accessible via three different circulation paths, for the different female user groups. The retrofit of the apartment tower rethinks the tower typology through a subtraction of spaces and creates vertical sanctuary gardens throughout and reclaims the spaces through the market stalls on the ground level.

The market stalls expand and contract via a track system to open up during the day and close at night. The stalls are skinned by shifting planter modules, making a screen that allows for medicinal herbs to be grown within reconstructed, physical camouflaging and to activate the fencing systems. The screen is morphed as it blurs into the shelter facilities where the wood modules reduce the thickness and become hung screens, maintaining its material qualities and patterning but no longer acting as planter boxes.

Future Research:

Designing a women’s shelter in Hillbrow warranted a focus on the extreme condition of violence against women and the camouflaging architectural and urban strategies that can emerge from that condition. In addition, researching the project lead me to believe that there is a need for designers and planners to consider broader categories of analysis of the public sphere as a disputed site in gendered and sexual relations.

Not only for Johannesburg’s Hillbrow, but for all global communities, we must challenge ourselves as designers to think of women beyond the registers of violence and victimhood and begin to contemplate how architecture and urban planning can create opportunities to support the responsibilities, pressures, and desires of today’s female population. We must discuss, honestly and openly, how the reframing of women in the city can inform new programs and facilities in pioneering ways.

1 UNite to End Violence Against Women

2 Crime Statistics South Africa

3 Rape Statistics & The Clark County Prosecuting Attorney

Mia Zinni received her Masters of Architecture from Columbia University GSAPP, where she was awarded the McKim Prize for Excellence in Design. Currently, she is a Designer at SHoP Architects in New York City and continues to contribute to academics at GSAPP, where she holds a consulting position for the Columbia Building Intelligence Program (CBIP).

Read more posts from the Stress and Wellness in Johannesburg series here.