November 29, 2021

A New Exhibition in Berlin Explores the Human Side of Architecture

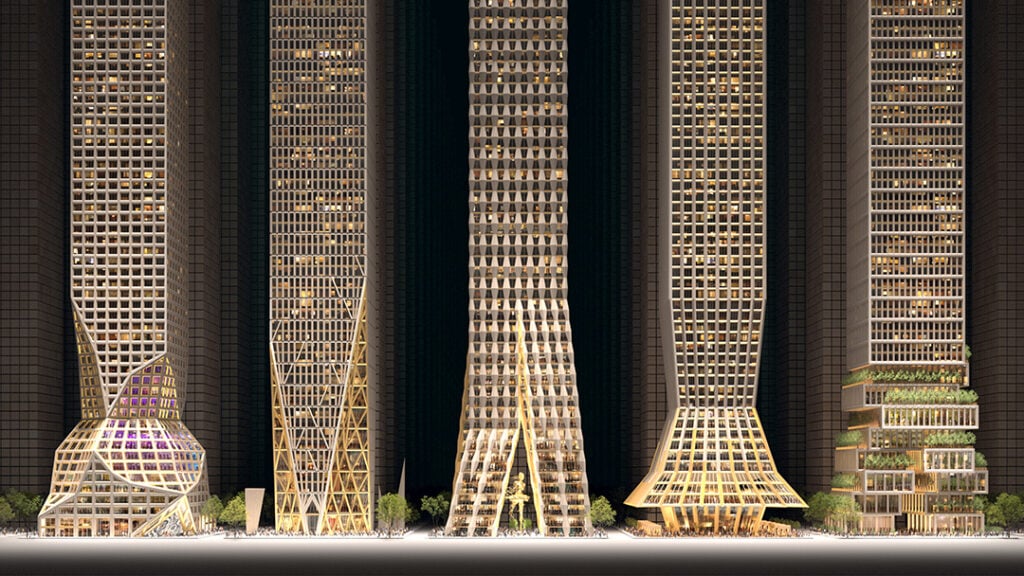

Wander further into the room, and you’ll discover that each tower has its own (unisex) name and personality. Blake, for instance, is an extrovert: The large awning over his/her base extends over the street, providing space for markets, concerts, and art exhibitions. Madison, on the other hand, contains rising terraces at his/her base, creating room for communal living spaces, long stay rentals, and micro apartments.

Indeed, the otherwise pristine columns’ bottom-heavy forms suggest clever new activations for tall building bases, which are too often predictable and uncreative. But more than that, they encourage guests to get down low and experience the structures in a new way, as if they were children again.

“Suddenly we feel like, hey we want to play. It’s a reminder of how curious we used to be when we were young,” says Hollwich, whose practice foregrounds innovation and surprise. “We need to tap into our childlike creativity to design for the future.”

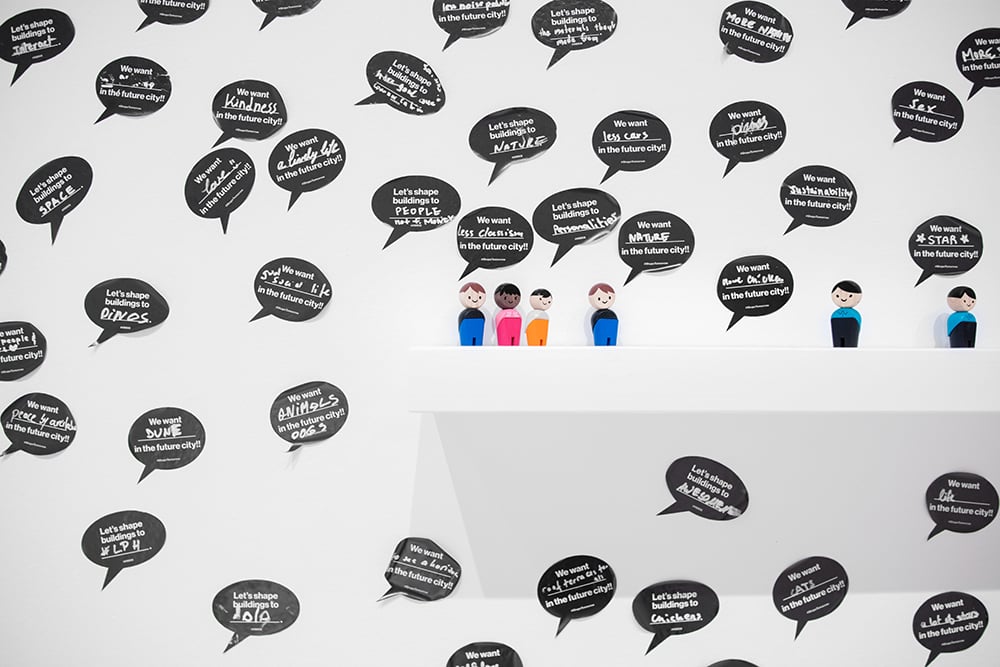

Another key to the show—and the firm’s approach to architecture—is its encouragement of participation. The towers are covered in small figurines, which visitors can add and manipulate however they like. (At the opening there were only about 30 Playmobil characters, but a trove of about 2,000 wooden characters by PlanToys were on their way; literally stuck in customs.) Already show goers had organized figurines into social circles, put them into compromising positions, and in one case set the scene for an upper floor dinosaur attack. After wandering further, visitors find a cache of stickers from which they can add their comments to the buildings, or to the walls around them. At the opening, guests criticized the show’s approach to inclusivity, called for more plazas for the figurines to meet one another, and advocated for greater sustainability, affordability, art, and human scale.

The show’s eagerness to capture feedback—Hollwich hopes to encourage more debate on social media and plans to include audience responses in the show’s catalogue and incorporate them into further research—is reflective of HWKN’s highly responsive approach, giving clients several designs to choose from, and encouraging them to engage throughout the process.

“Suddenly they feel empowered,” says Hollwich, who likes to provide about ten options for each project. “They feel like they can respond to architecture, which normally pretends there’s just one solution. That’s not right. There are hundreds of solutions, and we have to find the right one, together.”

Hollwich adds that such inclusivity creates better buildings, filled with more expertise and energy.

“The client knows a lot about a place and what they need to realize,” he notes. “It’s such a fun process. You have this incredible buy in, where everyone feels ‘I kind of designed this.’ If my client feels like they designed it, and the city feels like they designed it, that is the moment when you can create excitement.”

Would you like to comment on this article? Send your thoughts to: [email protected]

Latest

Profiles

Zoha Tasneem Centers Empathy and Ecology

The Parsons MFA interior design graduate has created an “amphibian interior” that responds to rising sea levels and their impacts on coastal communities.

Viewpoints

How Can We Design Buildings to Heal, Not Harm?

Jason McLennan—regenerative design pioneer and chief sustainability officer at Perkins&Will—on creating buildings that restore, replenish, and revive the natural world.

Products

Behind the Fine Art and Science of Glazing

Architects today are thinking beyond the curtain wall, using glass to deliver high energy performance and better comfort in a variety of buildings.