July 31, 2019

SFMOMA Ventures Into Outer Space With Its Latest Design Exhibit

Far Out: Suits, Habs, and Labs for Outer Space showcases visionary concepts by the likes of Raymond Loewy, Foster + Partners, Neri Oxman, and more.

Opening just after the 50th anniversary of the Apollo 11 moon landing, a small but potent exhibition at SFMOMA is well timed to remind us of how our hopes for space exploration and habitation have been fueled by evocative designs over the decades. Despite its title, “Far Out: Suits, Habs, and Labs”—on view through January 20, 2020—doesn’t concentrate on the current crop of gee-whiz ideas. Rather, it mixes realized and conceptual designs, primarily from the heyday of space exploration in the 1960s and ‘70s, along with some more contemporary proposals for exploring and living in outer space.

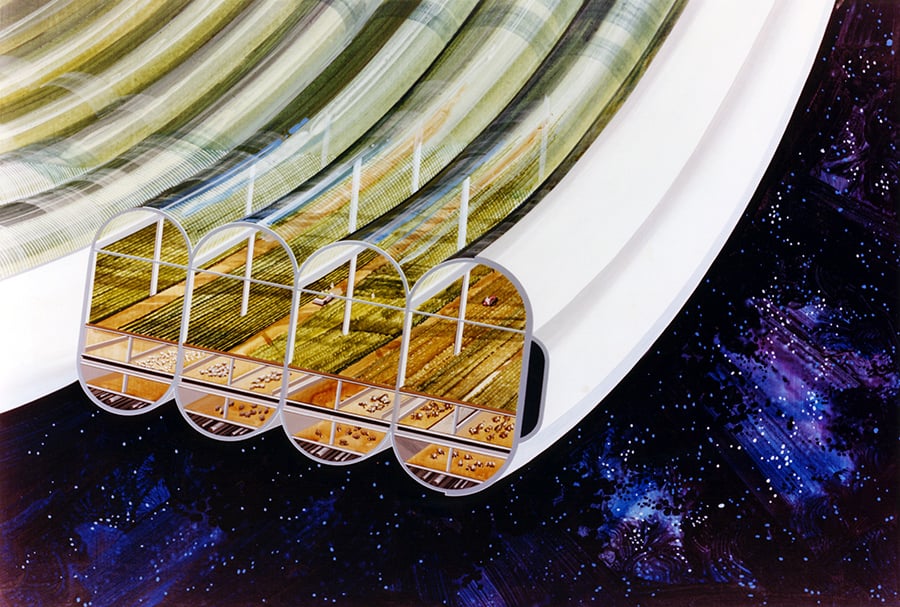

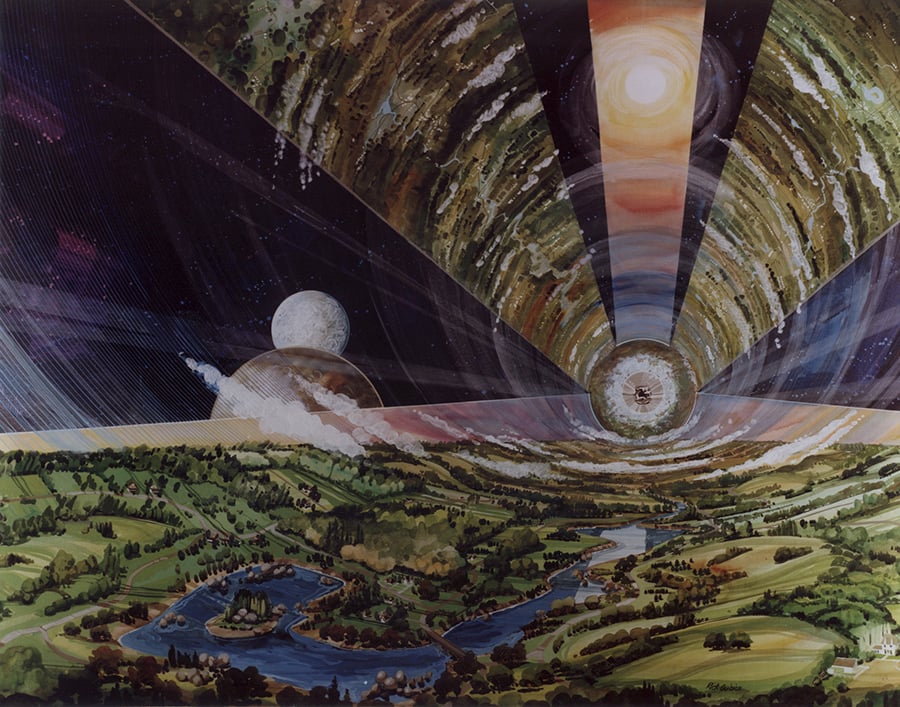

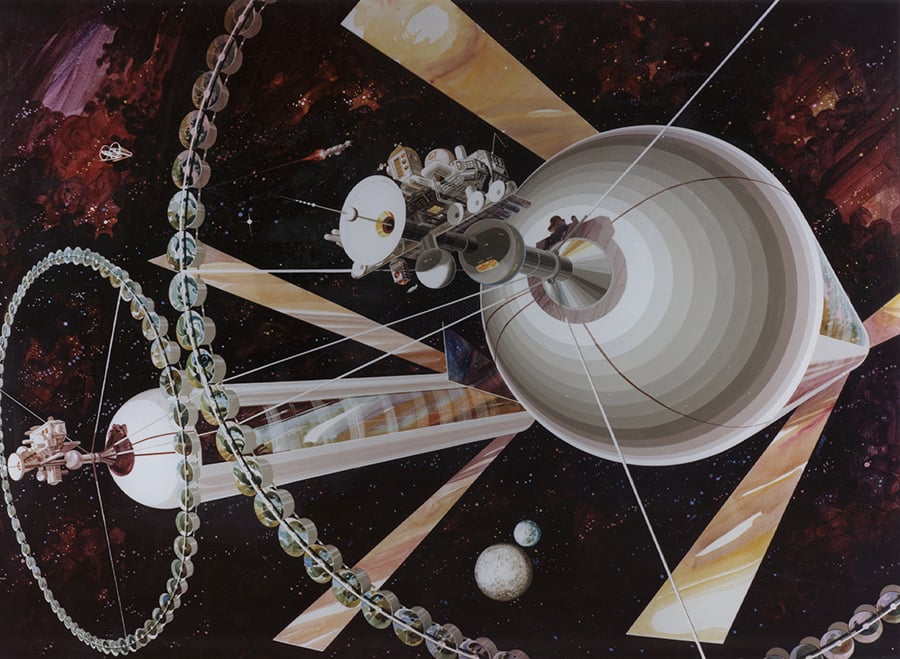

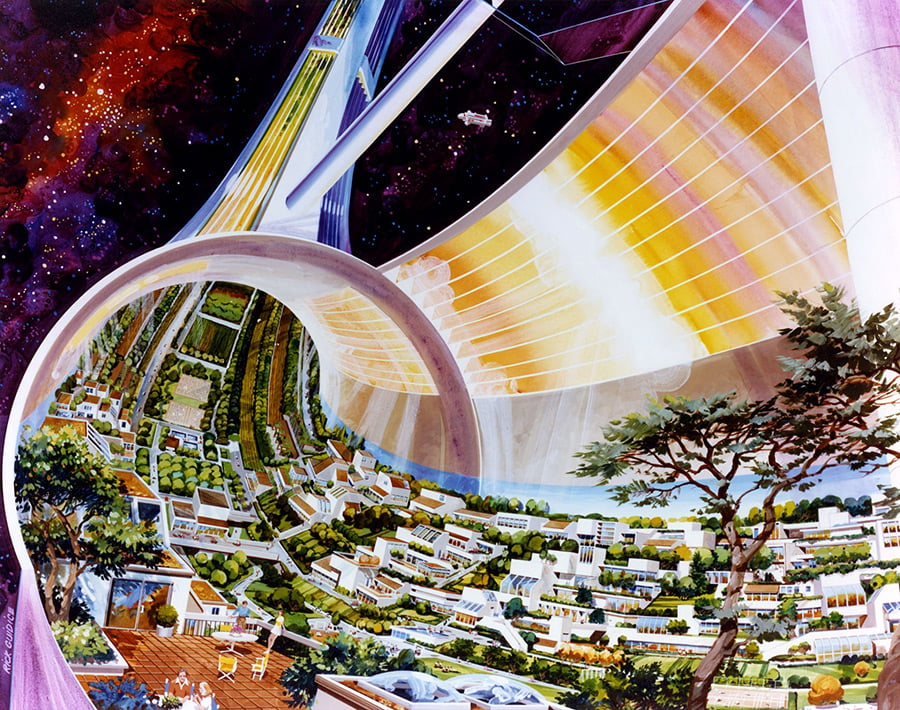

The exhibit’s main wall features a chronological display of books, drawings, models, and film clips that provide a brief overview of significant design ideas for outer space. In the early ‘50s, the popular magazine Collier’s published a special series called “Man Will Conquer Space Soon,” with illustrations that captured the public imagination, showcasing the role of designers in selling the dream. Six years after the Apollo landing, NASA convened a group of scientists and academics to envision a free-floating space colony; the result was physicist Gerard O’Neill’s 1976 book The High Frontier: Human Colonies in Space, whose concepts are rendered in a series of paintings that are on display for the first time outside of NASA. Wonderfully detailed, they make space look inviting and familiar, with improbably lush landscapes. “Scientists were realizing that illegible sketches weren’t going to get commercial or government buy-in,” says curator Jennifer Dunlop Fletcher. “The renderings really get to accessibility by a broader audience.”

The challenge of making actual space travel comfortable for humans was, back in the day, the charge of designer Raymond Loewy, who was the first to introduce a porthole window to space—as seen in his 1968 drawing of “Extra Vehicular Activity”—along with other ergonomic comforts to Skylab, NASA’s first space station. Fast-forward to present-day, when multiple companies are gearing up for space tourism. The Philippe Starck–designed guest quarters at the planned Axiom Station, as shown in a 2017 3D visualization, are envisioned as luxuriously padded capsules with tufted upholstery.

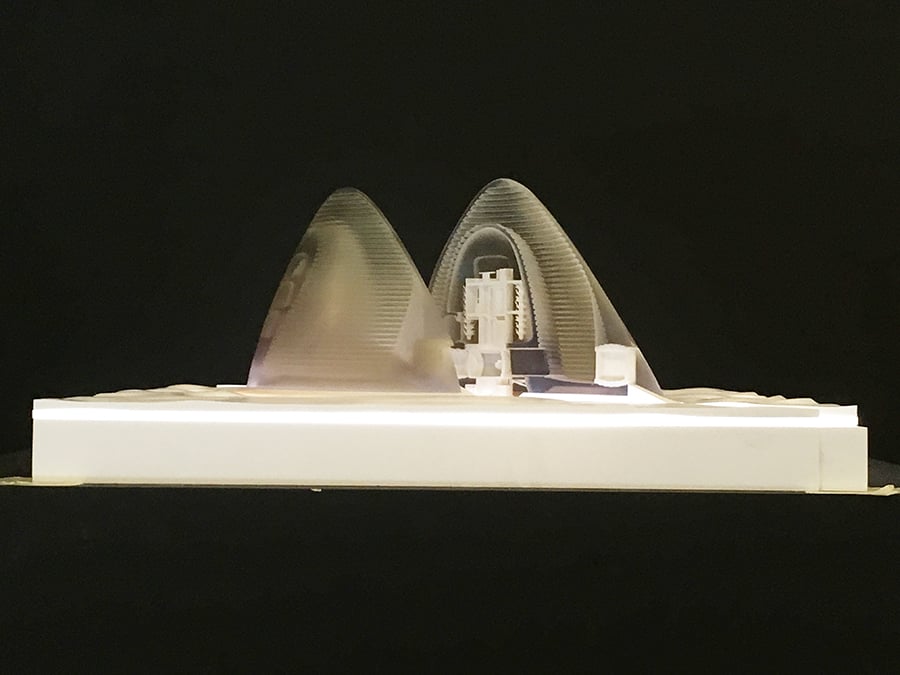

Thankfully, luxury isn’t the only 21st-century space innovation: many architects are looking to 3D printing as a practical solution for building on the moon and other planets, where materials are tricky to import and labor is virtually nonexistent. There’s a 2012 model by Foster + Partners, explained in detail by an accompanying video, of a Moon research base that begins with a large inflated scaffold that robots coat with layers of moon dust, creating a more solid structure. Similarly, a 2015 model by Space Exploration Architecture and Clouds Architecture Office proposes mining Martian polar ice for water to generate a translucent shell that would facilitate agriculture. Cal Poly Pomona’s architecture department has come up with alternative idea: a simple but expressive model from 2018 represents a cylinder that is light enough to be transported and then unrolls, like a roly-poly bug, to form a long structure.

Instead of the large clunky spacesuits that are de rigueur in space, might there be more elegant solutions? At the center of the exhibit, along with four classic real-world spacesuits, are two intricate and colorful wearables of 3D-printed plastic from the 2014 Wanderers series by designer Neri Oxman. Designed to augment a human body to suit the rigorous environments of various planets, one is a chest plate that looks like a mass of bronchioles, envisioned to filter air and provide oxygen; the other, a florid neckpiece, would function as a protective exoskeleton. It’s not a big leap to image that in the future, we may need to wear something similar on Earth to survive our planet’s degrading environment. While Buckminster Fuller envisioned floating cities inside his geodesic domes, the exhibit includes his 1928 drawing depicting Earth and its resources, an idea he would elaborate upon in his 1968 book Operating Manual for Spaceship Earth, where he warned of a “spin-dive toward oblivion” absent global stewardship of said resources. Says Dunlop Fletcher, “You can see that along with an expanded view of the universe, the perception of a more fragile Earth keeps coming back as a theme.”

You may also enjoy “10 Design Cities You Should Know.”

Would you like to comment on this article? Send your thoughts to: [email protected]