April 4, 2019

Taller TO Explores Movement in Architecture on Mexico City’s Unsteady Ground

Firm founders Carlos Facio and José G. Amozurrutia’s commitment to environmental and social responsibility has grounded the studio as it expands.

Composed of steel rods topped by copper plates that, when touched, vibrated to create sound, TO’s 2018 installation at Mexico City’s Museo Experimental el Eco was simple, immersive, and site-specific. It turned an enclosed patio hidden behind the museum’s facade on Calle James Sullivan into both a gallery and a live instrument. The work was a breakthrough for the Mexico City architecture firm, blending its founders’ long-standing love of music with other areas of fascination: impermanence, craftsmanship, and movement.

Carlos Facio and José G. Amozurrutia met as kids playing soccer, then formed a cover band, playing music by the Beatles and the Doors (their designs’ musical inclination isn’t a coincidence). Both studied architecture at the National Autonomous University of Mexico and worked at Taller de Arquitectura with architects Mauricio Rocha and Gabriela Carrillo. After a period apart pursuing other experiences and education, the duo reunited in 2015, teaming up with Rocha and Carrillo to design the Hermès pavilion for Milan Design Week. The same year, the pair formed TO. “At that stage in our careers, we decided it was time to make a go of it,” recalls Facio. They set up shop in a converted warehouse in the neighborhood of Coyoacán—keeping a drum set in one corner in case the urge to play struck—and began renovating houses and apartments throughout the city.

Business as usual came to a halt on September 19, 2017, when a 7.1 magnitude earthquake struck near Mexico City. The official death toll was 369, and thousands lost their homes. In response, TO joined ReConstruir México, an initiative by architects volunteering services to earthquake victims. Through this network, Facio and Amozurrutia designed a four-room house of locally produced brick for a woman and her children in the town of Ocuilan. Several nonprofits, including ¡Échale! A Tu Casa and Piensa Sostenible, contributed to defray the building costs.

The earthquake was a tragedy, but it was also a pivotal moment for the firm. “It made us think about a very basic principle of architecture, which is how the structure reacts to movement,” says Amozurrutia. Soon after, in December 2017, TO won two important annual pavilion competitions—Museo Experimental el Eco and Mexico City’s Fería de las Culturas Amigas (FICA). In both projects, TO explored movement and change—“how ephemeral things can become permanent, and how something permanent, like a house, can have a lighter impact on its environs,” says Amozurrutia. For example, when the Eco pavilion closed last May, its copper plates, fabricated by local artisans, were resold.

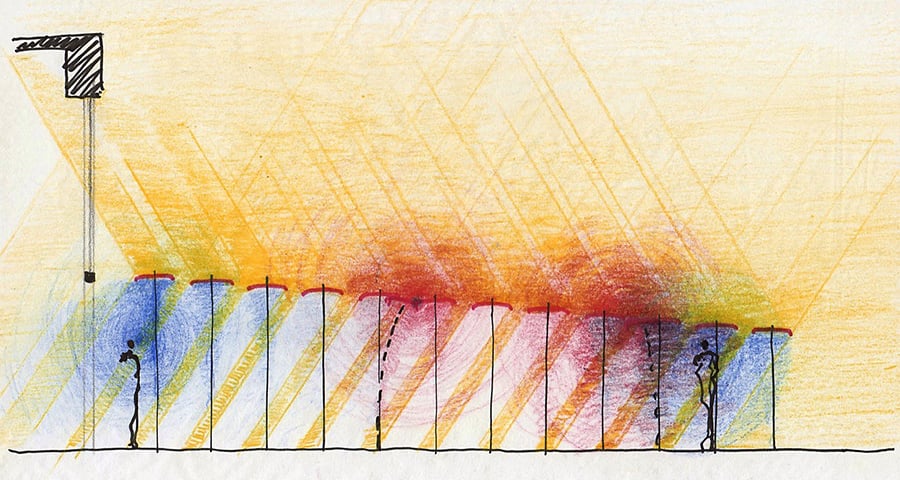

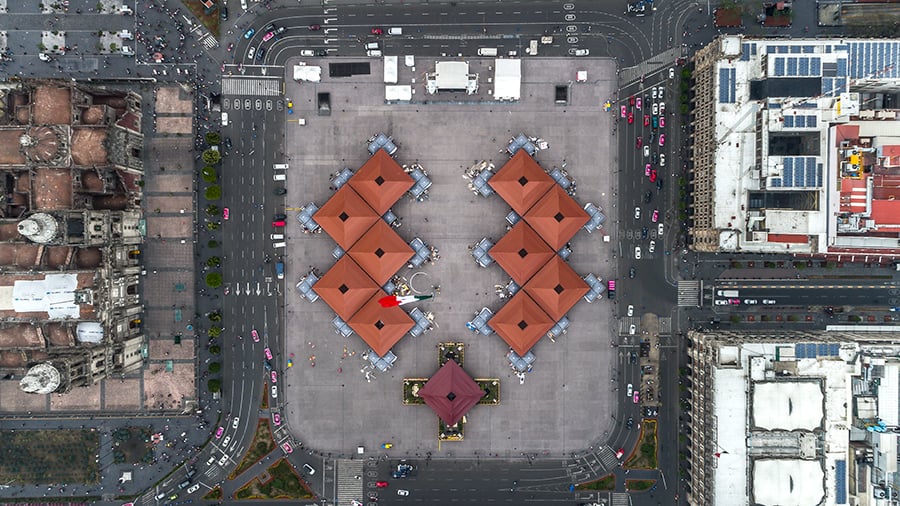

TO approached the same concepts on a larger scale with the FICA pavilion in 2018. The fair—held each spring for one week in the Zócalo, the massive public square atop the ruins of Tenochtitlan—attracts over five million visitors. To accommodate the crowds, TO designed canopies that formed wide pathways and allowed air circulation. The rust-colored structures were designed for eventual reuse by communities affected by the 2017 earthquake and served as a contemporary counterpart to Teotihuacán’s pyramids.

TO’s commitment to environmental and social responsibility has grounded the studio as it expands—adding designers Úrsula Rebollar, Álvaro Martínez, and Mónica Lamela. And it provides a direction as TO reaches international audiences: The firm is a finalist for the 2019 Young Architects Program pavilion at MoMA PS1 in New York City.

“Architecture is not a blank canvas,” says Facio. “We always have to understand the melody and the rhythm of a place.”

You may also enjoy “5 North American Makers You Should Know.”

Would you like to comment on this article? Send your thoughts to: [email protected]