May 19, 2022

Speed and Sustainability: The Luisenblock Shows What’s Possible with Mass Timber and Prefabrication

The tender was addressed at private developers who would guarantee to stay within the project’ tight timeline and budget. In May 2020, the tender was won by a consortium of Primus developments, Berlin-based Sauerbruch Hutton Architects, and the Austrian building company Kaufmann Bausysteme—a specialist in timber construction. They suggested a construction in prefab timber modules, a system that the three partners had successfully applied before with a large student’s housing in Hamburg (2014–2017), called “Woodie”. The experience they gained building Woodie played a major role for the new “Luisenblock”, ranging from the organization of the timber prefabrication process to sourcing wood and detailing the quick assembly on site. As soon as the contract was let, Sauerbruch Hutton started planning at full speed while Kaufmann worked in parallel to set up a temporary factory for the construction of the wooden modules in an empty Berlin industrial hall. They occupied an empty industrial hall in southern Berlin that had previously been used for the production of the infamous “Platten”, the prefabricated concrete slabs that until 1990 had been a major material for residential buildings all over the Eastern Bloc.

Construction of the “Luisenblock” started in October 2020, barely five months after it was commissioned. By April 2021, the factory was operating at full speed: Each working day, six massive timber modules were fully assembled at the factory, transported to the construction site, and assembled by the early evening. No doubt, this building was as quick, efficient, and sustainable as it gets in terms of construction. But what about the architecture?

Under these circumstances, the building’s design was kept deliberately simple and straight-forward. The prefab modules, whose size is proscribed by a maximum truck load, defines the building’s grid. The architects arranged these modules in a large H-shape much like a typical inner-city Berlin building block, but with two open courtyards. The southern yard acts as main entrance connecting the building to the government district and the Reichstag. To the north runs the city’s main train line running on a historic brick viaduct that cuts through the city center. It is Berlin’s busiest track with trains following each other in high frequency, both day and night. Accordingly, the northern courtyard is protected by a wall of glass and steel, seven stories high, like a permanent scaffolding that triples as noise protection, fire escape route, and outdoor break area for the staff.

While the building is made of 75 percent wood, it doesn’t show on the outside. Matthias Sauerbruch, partner at Sauerbruch Hutton, explains, that at an early stage in the design process all the partners agreed that “a public building in this specific context of the government district, a timber facade would have been too out of place.” To propose a wooden construction seemed innovative enough at this point. Instead, the building is wrapped in a weatherproof shell of recycled aluminum and glass. During the day, it shines in a modest silver, carefully accentuated by vertical strips of colored glass. The use of color is a trademark of Sauerbruch Hutton Architects since the start of their office in the 1990s, though here they restrained their palette, as befits a government office.

The result is a modular wooden building, that shows neither its modularity nor its wooden-ness to the outside. To experience the wood, you’d have to work here, as inside timber is omnipresent as a visible (and fragrant!) material in walls, ceilings, and furniture. Most of all, it is a humble and quiet building. But if you know about its wooden heart, then the message is clear. Then, the Luisenblock whispers insistently that it is possible to change the construction industry’s business-as-usual attitude, even in the dense city-center of Berlin and for a governmental building with all its restrictions. Best of all, it can be done in time and on budget.

Would you like to comment on this article? Send your thoughts to: [email protected]

Related

Profiles

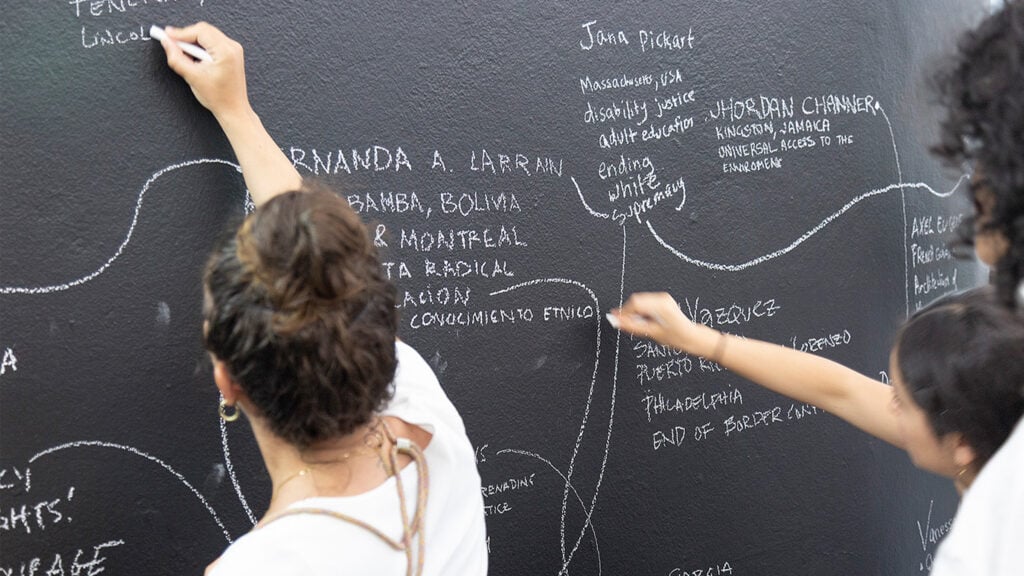

WAI Architecture Think Tank Approaches Practice as Pedagogy

Nathalie Frankowski and Cruz García use their practice to help dismantle oppressive systems, forge resistance spaces, and reimagine collective futures.

Products

Functional Beauty: Hardware That Does More Than Look Good

Discover new standout pieces that marry form and function, offering both visual appeal and everyday practicality.

Profiles

The Next Generation Is Designing With Nature in Mind

Three METROPOLIS Future100 creators are looking to the world around them for inspiration.