January 6, 2014

Uncovering The Artful Posters of the Soviet Film Industry

A London gallery provides an in-depth look at little-known designs from the erstwhile Soviet Union.

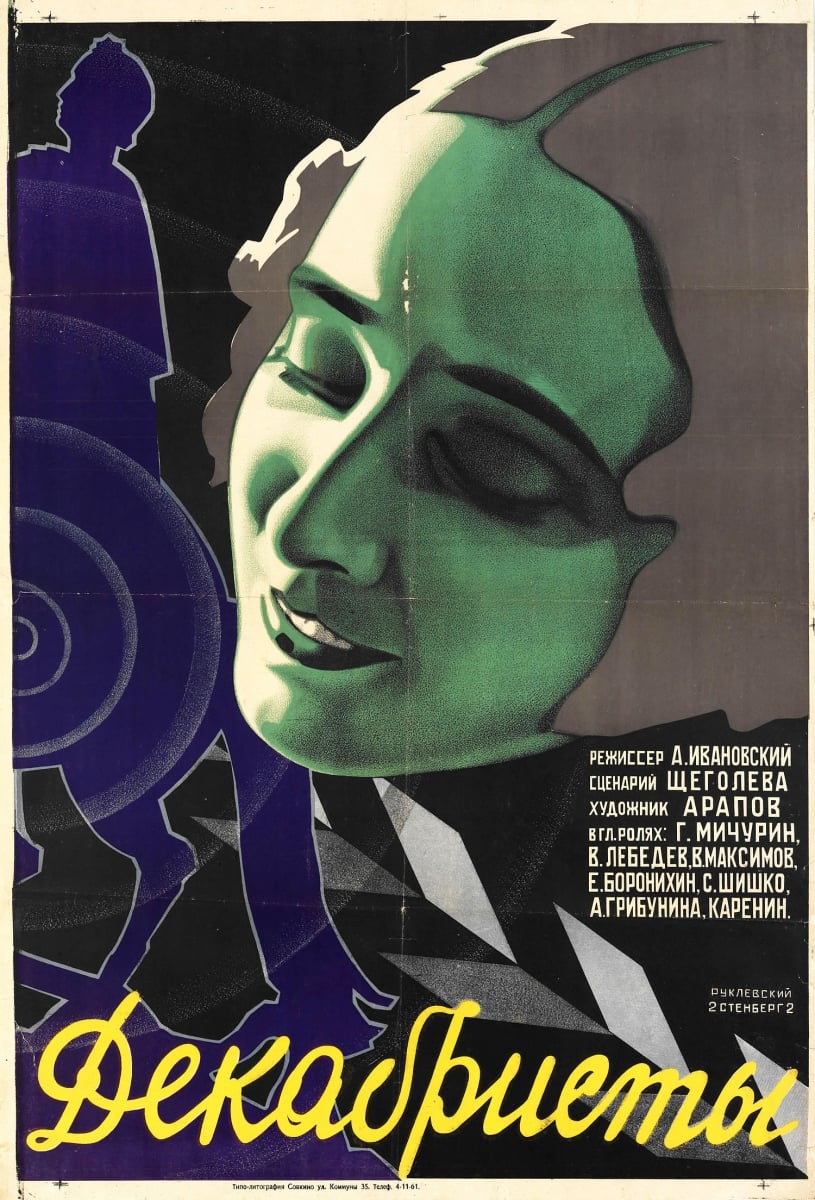

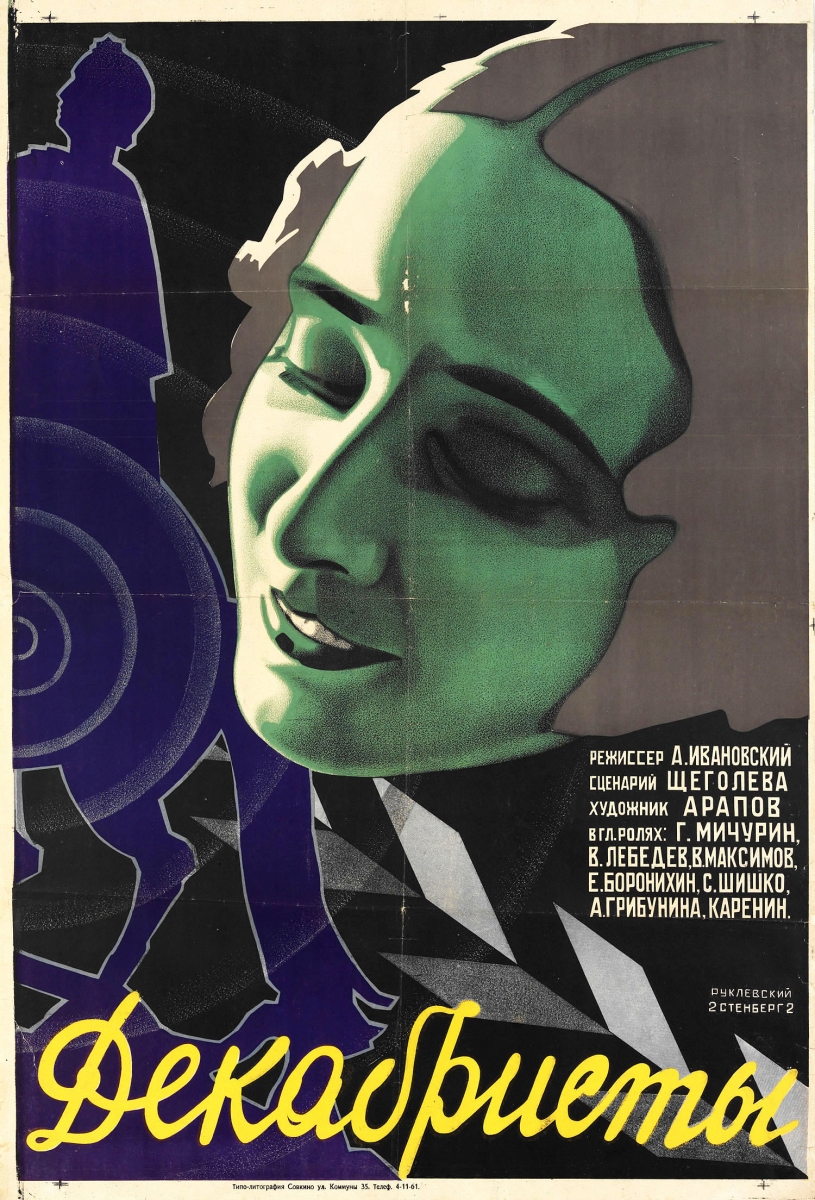

Influenced by constructivism, film theory, and avant-garde theater, the film posters by Georgii and Vladimir Sternberg form the core of GRAD’s Kino/Film exhibition. Above: Decem- brists, 42 by 28 inches, 1927

All images courtesy GRAD-London

“Most of the Russian art you see in London is very much influenced by the auction houses. They dictate the taste,” says Aliya Sayakhova, a research assistant at the Gallery for Russian Arts and Design (GRAD), a new not-for-profit space dedicated to a field that its founders feel is under-or even misrepresented. The focus on price tags puts a whole different spin on things, says the gallery’s assistant curator, Alexandra Chiriac. “It means you’ve selected an object because you think someone is going to buy it rather than because it is interesting or says something about Russian art history.”

The team behind GRAD is well-placed to educate and disseminate. The gallery’s director, Elena Sudakova, ran the successful G.O.S.T. Gallery (which specializes in late nineteenth- and twentieth-century works on paper) in Moscow for ten years and opened GRAD after completing an MA in Russian Art at London’s prestigious The Courtauld Institute of Art. Also doing the course with her were Chiriac, who previously worked in Sotheby’s Russian department, and Richard Barling, now a consultant for the gallery but with a long career in academic publishing behind him.

The gallery’s first exhibition, See USSR—dedicated to a series of Russian posters printed to entice foreign visitors to the former Soviet Union in the 1920s and ’30s—launched last June and saw hundreds of visitors in its final days. Its second show, Utopia Ltd., brought to life some of the radical designs and ideas of the Russian constructivist artists. “What we want to do is bring things over that really haven’t been seen before,” says Chiriac. In keeping with that mission, the gallery’s third show, Kino/Film: Soviet Posters of the Silent Screen, which opens this month, will examine the relatively unknown golden age of Russian film ads.

The backstory to this show is fascinating. With the increasing popularity of film , the government realized that the medium was an excellent propaganda tool for the largely illiterate masses. So there was a surge in both foreign and domestic film production in the 1920s, and an urgent need to promote the films. “A new visual language was created by these young artists who were trying to find novel ways of advertising the films,” says Chiriac. “These posters were different from the Hollywood posters of the same time, which were more narrative in style. The Russian posters are very graphic and almost constructivist.” A hundred years later, the posters still look bright, fresh, and modern.

Georgii and Vladimir Sternberg’s poster for Sergei Eisenstein and Grigori Aleksandrov’s film October, 1926

After Kino/Film, the gallery is planning to host an exhibition called Apartment No. 5, about a group of avant-garde artists who are also, unsurprisingly, not widely known in the West. “They started getting together around the mid-1910s in a studio apartment in the Academy of Arts in St. Petersburg,” explains Chiriac, gathered by Nikolay Punin, an art critic who died in a gulag because he wouldn’t compromise his beliefs or sever his ties to the Western art world. Almost a century on, Sudakova and her team still believe that Russian and Western art historians “don’t really talk to one another,” says Chiriac. “We want GRAD to become a platform where this kind of communication would be encouraged.” The early signs are promising.

Poster for the film Looping the Loop, 1929

The Stenberg Brothers film, A Perfect Gentleman, 1928

Sports Fever, 1928