July 23, 2013

Urban Views: Artists Reflect on Our Built Environment

New book on the American landscape updates a traditional art form and its subjects

Our renewed interest in the landscape may be interpreted as a sign of a growing awareness of the natural environment and regional architectural expressions, as well as a new fascination with the urban form in all its grubby and exalted iterations. Painted Landscapes: Contemporary Views, a new book from Schiffer Publishing, showcases the work of a variety of artists observing our built environment one house and garden, one city- street, one abstract building detail at a time. Here I chose to excerpt the book’s introduction to a chapter called Urban Views.–SSS

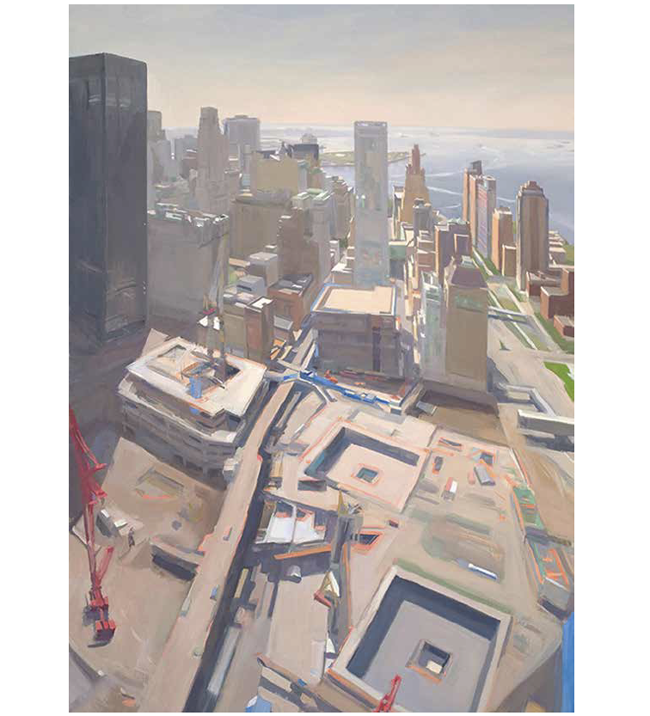

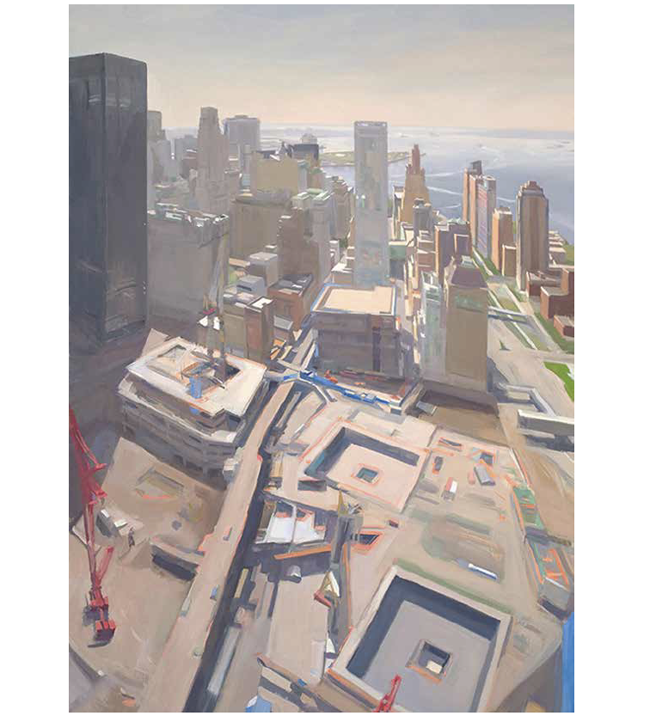

Fig. 28: Diana Horowitz. World Trade Center Reflecting Pools and Harbor, 2010. Oil on linen: 42 x 30 inches.

Courtesy Hirschi & Adler Modern, New York

Oftentimes a landscape is not so pristine and the view is not so green. In urban areas, bridges, skyscrapers, strip malls, roads, tunnels, and train tracks cover the earth, extending skyward so as to obscure the natural horizon. Concrete, glass, and steel replace land, sky, and vegetation in these metropolitan environments. It is these sites that are, through the eyes of an artist, urban landscapes. These congested, constructed views of the places we live and work are cityscapes rendered beautiful or challenging, appealing or repulsive in their visual dissections of place.

Artists have traditionally used their paintings of cities as tools for documenting social, political, and economic conditions. Urban seaside ports were often depicted as scenes of commerce in the nineteenth century with the full range of architecture and harbor activities laid out in a single composition. Often these paintings provided people living far away with their only images of distant ports of call. These urban paintings acted as the photographs of their day and were meant to capture the essence of a place as well as its major landmarks. Political considerations, too, made their way into urban landscape painting in America beginning in the days of Revolutionary conflict with England.

Fig. 42: Richard Estes, Staten Island Ferry Arriving Manhattan, 2011. Oil on canvas: 37 x 65 5/8 inches. Image © Richard Estes.

Courtesy Marlborough Gallery, New York

In the early twentieth century, paintings of New York declared patriotism. Flags on 57thStreet, Winter, 1918, by Childe Hassam (1859–1935), a proponent of the French Impressionist style of painting, announces America’s participation in World War I with exaggeratedly large and brightly colored American flags hanging over the street in contrast against snowy, white winter scene of busy streets, elevated train, and buildings. Painters of the era also depicted economic conditions by way of their cityscapes. In contrast to the Impressionist style of the day, the Ash Can School of painters–a group of eight artists so named by a critic’s derogatory comments upon seeing an exhibition of their work–depicted gritty daily life on the more down-at-the heels streets of New York.

Following this winding tradition of painting urban scenes, the Modernists took an alternative approach. Rather than simply documenting the city or presenting genre scenes of street life, the Modernists painted the urban centers as grand temples, as the pinnacles of innovation and industrial success and the cultural meccas of modern life. Georgia O’Keeffe’s Radiator Building, 1927, for example, shows the single edifice in the center of New York City as a grand monument lit up against the night sky. Other artists took this a step further and presented urban scenes with near-religious reverence for the impact of commerce on everyday life. Precisionist painter Charles Sheeler (1883–1965) shows a simple factory as the modern-day temple in River Rouge Plant, 1932. In this work, the large building forms the heart of the community life, filling the canvas from left to right, its smokestacks pointing skyward, announcing its importance in scale and orientation. Joseph Stella (1877–1946) proclaims the importance and thrill of engineering in New York City with his Brooklyn Bridge: Variation on an Old Theme, 1939, one of his many depictions of the structure he saw as an American icon. In these works, the commercial, urban landscape is revered and presented with grandeur and veneration for its place in modern life.

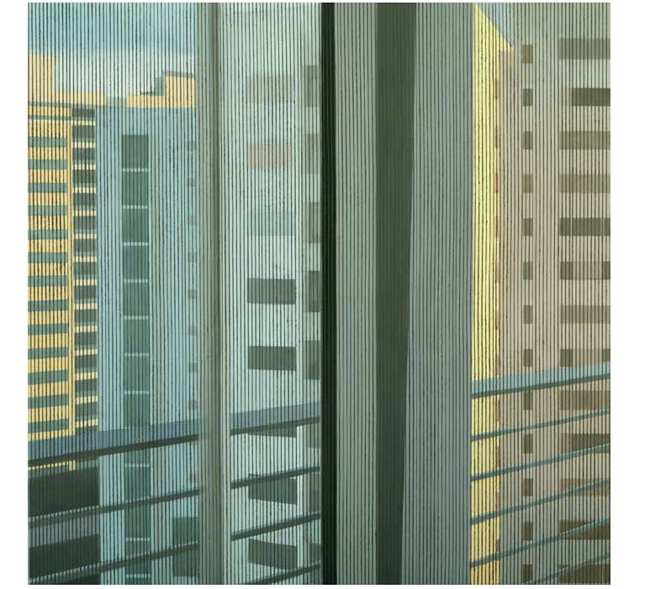

Fig. 45: Sarah McKenzie. Scrim, 2011. Oil on canvas: 48 x 48 inches. Image © the artist.

Courtesy of the artist, Jen Bekman Gallery, New York, and Rule Gallery, Denver

Other artists took further artistic license with urban scenes, creating what can be seen as compilations of the architecture, noise, and activity of the city. John Marin’s (1870–1953) Region of Brooklyn Bridge Fantasy, 1932, heaves and sways with opposing diagonal lines underscoring the energy, movement, and chaos of the city, the cacophony of noise and color in the street reflected in the multi-faceted composition’s broken-up picture plane and contrasting colors.

By the 1960s and 1970s, another urban artistic movement took hold in New York and on the West Coast after a popular respite from representational painting during the 1950s and early 1960s in favor of abstract painting. Photorealism, a hyper-sensitive reinterpretation of Sheeler’s smooth, exacting Precisionism of the 1930s, was based on photography and attempted to paint the urban landscape such that it was difficult for the naked eye to distinguish between a painting and a photograph. Such extreme realism recalls the historic tradition of trompe l’oeil—the optical illusion tradition dating back centuries to ancient Roman wall paintings—yet these painters of the mid-twentieth century turned their highly focused attention to the urban environment for the first time.

Fig. 47: Sarah McKenzie. Patriot, 2011. Acrylic on canvas: 48 x 72 inches. Image © the artist.

Courtesy of the artist, Jen Bekman Gallery, New York and Rule Gallery, Denver.

Formally, the color palette of the urban landscape goes in many directions and has from the Modernist period forward. In some works, the color palette is muted and composed of, ironically, earthy tones of brown and grey. These colors reflect the industrial materials used in the urbanization process and sometimes the scars left by mechanization and industrialization. Alternatively, the same colors reflect the natural environment but in their use as the building blocks of a city. In other paintings, the color palette is aflame with man-made color in street signs, neon lights, and the other accoutrements of a packed urban environment. Such riotous color could be celebratory or reflective of man’s encroachment upon the natural world.

Lauren Pheeney Della Monica is a New York based art consultant who specializes in advising private clients on building art collections.