February 18, 2013

What Humanism Can Tell Us About How We Encounter Architecture

The mind that encounters architecture

Parts 1 and 2 of this series of posts introduced the idea of opening up a broader perspective on architecture, landscape, and urban design that I’m calling “a new humanism”.

Parts 3 through 9 outlined the first step – tracing out the evolutionary origins of innate skills, propensities, and motivations that lead us to respond to built environments the ways we do – from the competitive drive for individual security, survival and prosperity to the equally deep-seated cooperative impulses that lead us to settle in communities. They explored our powerful links to the natural world, the continuous search for order and orientation and the creativity that gives us a unique niche in every ecosystem we invade.

Part 10 now starts a series of eight posts that take a deeper look at “experience” itself – what is it like to be there – focusing on how the evolved mind that encounters architecture works in practice.

First though, a note about words: “Architecture” is simply a brief way to say architecture, landscapes, and urban places – “the built environment.” And I use the term “designers” as an abbreviated way to say “architects, landscape architects, land planners, urban designers, interior designers, and the decision-making clients and governments who direct them.” This does not, of course, imply a hierarchy of professions, but the word “architecture” has a general sense of an overall, organized structure of things. Likewise, I am not implying the common distinction between architecture as “high art” and “mere building”. We live in both – and mostly in the latter. The total built environment is the art and science that no one can escape.

“Encounters” is more complex. The whole body is involved. Like searchlights, all of the senses are continually seeking out information – promises of pleasure and opportunity, threats and trouble, orientation and aids to navigation. And forms, light, color, sounds, warmth and movement, become sequences of “cues,” signs and symbols that call up memories and beliefs, magnified by our body-state and linked-in emotions. The searches and these sensations naturally become interlaced, consciously and unconsciously, with other streams of thought and feelings already flowing, “in here”, along channels shaped by our specific role or purposes of the moment. In a sense, it’s like the theater with playwright, director/actors, and audience interacting to create “experience”.

“Mind” necessarily means mind-and-body, but I am separating them here in order to explore first what seem to be favored channels in the brain – predilections, propensities, capabilities – that were prepared by natural selection. And, as used here, a “mind” is not an entity, but the result of flowing chemical and electrical action in a brain. In this sense, the mind is what the brain does. Essentially it makes images that it manipulates with what we call thought, predicts the future, plans for it and steers behaviors.

The important point is that – consciously but mostly unconsciously – it coordinates our intentions to survive and prosper with what we have learned in the past, what our senses are detecting now, and what is happening in the imagination. While the logic may be hidden from view, a mind constantly finds or creates coherent, orderly patterns and then judges, decides and we act.

A mind, of course, is never still, but flexible and changing moment-to-moment and place-to- place as experiences pass through and leave their traces over a lifetime. Through those changes, though, and across a multitude of person-to-person variations, threads of continuity keep re-appearing, and that is what I’m exploring. What follows seems to me a workable outline of ways that human minds are likely to function in practice – including minds formed in today’s rapid-fire bytes of information – as they encounter the places we design for them.

The response begins: first impressions, reasoning, learning

An “experience” starts with the first milliseconds of perception, when everything we are – our bodies, our past, and the motivations of our “personal project” – engages the people, natural setting, and built environments around us. All of our senses scan for useful information and the signals received are channeled immediately to primitive parts of the brain where defensive, welcoming or aggressive reflexes spring into action. “Approach or avoidance” is the first decision made, and it’s a whole-body experience. Emotions and “gut feelings” are triggered; the body “feels” what the mind does not yet “know”, and we discover ourselves responding. Because time increases potential risk, we draw quick conclusions and accept good-enough shortcuts. In other words, just below our conscious awareness we live in the evolved heritage that’s kept us alive.

Those first mind-body changes that heightened the senses and focused attention go on to activate the cognitive, reasoning parts of the brain, and the working memory goes to work; the instant reactions become woven into our vast reservoir of learning and remembered experience; chains of associations link-up, and abstract ideas, theories and imagination all come into play as we fill in gaps in information, visualize future consequences, and plan our next move.

Naturally connections are made most readily along well-traveled circuits of memory and pre-conceptions, some going back to the imprints of early childhood, and some just recently “primed” in the mind and muscles. In other words, an experience is enormously expanded as the first sensations race along the multiple mental pathways that were first framed by evolution, then channeled by culture, then refined and deepened by more learning and reflection, and finally fixed as memories.

In a first-time visit to a place, when we haven’t yet learned its patterns – in a sense its “script”, we quickly sort out “new” from familiar. Surprises, unexpected and unfamiliar sensations that are pioneering along new channels demand more attention – more energy – until we can find or invent ways to reconcile them with what we’ve learned earlier. Then we smile at the reassurance, or, if the mismatch is too great, retreat and rethink.

A lot can happen in a second – as well as over hours or years – as we enter into a clear relationship with a place. The immediate gut reactions quickly become rationalized into a settled understanding, decisions, and behavior. Thanks to our fine-tuned detection systems and long term memories we’re often – but of course, not always – right.

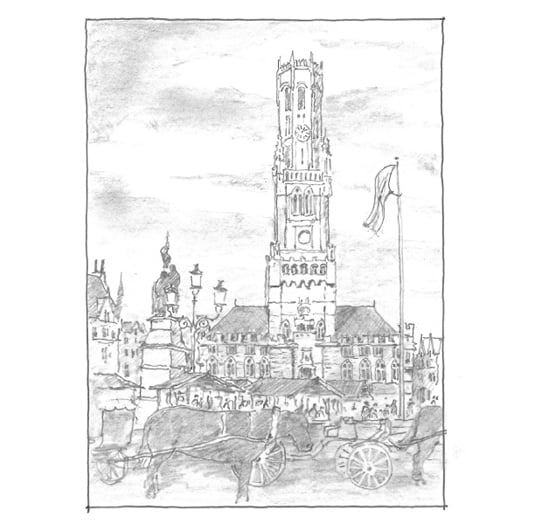

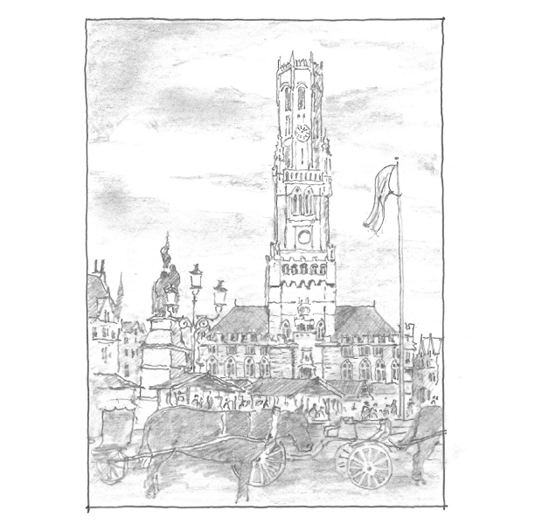

The Belfry Tower in Bruges – a competitive symbol – like a challenge – a deliberate, emphatic first impression of the city’s power and wealth, visible for miles along the canals of the flat Flemish countryside.

For designers, perception of a built environment is quickly dominated by the trained sectors of the brain, shaped by our mission of the moment, expertise, reasoning, and a constant presence of the drive for personal expression. The important point, however, is that in others’ perception – in our clients’ and stakeholders’ experience – the first impressions framing an event are likely to be literally un-reasonable and they may relate to things – sounds, scents, personal memories – often outside the designers’ control. But a mix of body-chemistry – specialized hormones and neurotransmitters – has inevitably been awakened. It lingers, and broader perspectives or analytical mental processes may or may not be convincing enough to redirect its momentum. We read different messages and tend to remember best what we saw first – and also last. And a mood that’s aroused or an emotional event – even a small one like anxiety about orientation or frustrating crowds, stress and feeling a loss of control, or, on the other hand, a sense of empathy and a friendly welcome, surprise or exhilaration – can take charge, amplify, and flood the channels of perception.

In these ways, the spontaneous first impressions set up one of the contexts that give a meaning to the total experience. The visitors’ “personal projects” of the moment may well be dominated by any number of high-priority preconceptions, blinding them to the designers’ intentions. Naturally, this can be a daunting challenge for designers working with fresh and complex ideas, especially facing a skeptical lender or citizens’ group rightly anxious about any change, or with the gateway messages inherent in a façade or lobby and the first “drop-dead” marketing statement made at a front door.

Yet the challenge has been met routinely in successful designs by those dedicated to learning – until they become intuitions – what’s likely to be happening in the mind and bodies of the people who are going to matter. Generations of church or palace builders, classically-trained architects around the globe, and more recently developers in retail, luxury resort or entertainment markets, have shown how skillfully that can be done, how forms and symbols, materials, entry points and prospects, can be used to evoke, instantly, specific survival-based feelings – order, clarity, a high or lowly status, links to the natural world, an impulse to explore further, a feeling of refuge and security or the promise of more rewards, up ahead, for the searching senses.

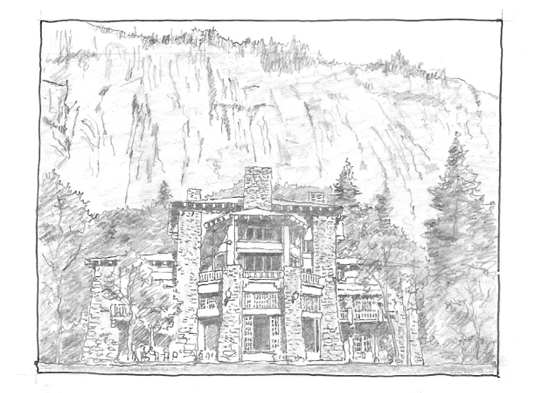

The Ahwahnee at Yosemite National Park brilliantly elicits a range of first impressions that capture the thrill of discovering and dwelling in one of the world’s great natural settings.

Today, however, we face an obstacle that we have created for ourselves. Many designers, trained in professional pride and advocacy, tend to partition work – often jealously like the old protective guilds – into the jurisdictions of architecture, landscapes, interior design, traffic and other engineering professions – and investors often require it for financial reasons – when in fact it is only the cumulative, interacting impressions that are experienced by our audiences. Although most designers’ vocabularies today include the word “teamwork,” in conventional practice we tend to use topographic surveys limited to property lines and design “my” project solely within a project’s contracted limits-of-work. Some treat land as a “clean slate.” There’s even a custom that architectural design ends a few feet outside the building. And today, mile after mile, acre after acre of what we build, with a few notable exceptions, still seems to be in a fruitless and repetitive competition of fragmented first impressions and introspective individuality beyond any useful or comprehensible complexity or contradiction. That’s an obstacle that a new broader humanism would be designed to demolish.

* * * *

Next: Every experience takes place in a mind already biased by intentions and expectations; and whatever a designer may intend, “my” focus is “me”. * * * *

This is the tenth of a series of posts that spell out a set of ideas called A New Humanism: in architecture, landscapes, and urban design. They’re about enlarging the way we think about design by applying, in day to day practice, a broader range of insights into the cutting edge sciences of nature and human nature — using them to understand how our evolved mind-and-body actually experience the places we design, and why people respond the ways they do.

Robert Lamb Hart is a practicing architect and planner educated at Harvard GSD and the University of Pennsylvania. He is a founder and a principal in Hart Howerton, a planning, architecture, and landscape design firm with an international practice out of offices in New York, San Francisco, London, Shanghai, Park City, and Boston. He believes that the design professions have been falling behind in their understanding of one of the defining enterprises of the Modern revolution, the application of the maturing, fast-moving sciences of ecology and human behavior — and the compromised results are showing.

Albrecht Pichler, who drew the sketches, is a practicing architect and a principal in Hart Howerton’s New York office.