July 16, 2018

Super-Sustainable Dwelling, Built to Push the Limits of Self-Sufficiency, Goes on View at U.N. Headquarters

A collaboration between Yale University, Gray Organschi Architecture, and the U.N., the CLT module was designed and built within a break-neck speed of five weeks.

The grassy enclave just north of the U.N.’s General Assembly building is no stranger to strange objects: there’s Arnaldo Pomodoro’s enormous, abstract bronze Sphere Within Sphere and Yevgeny Vuchetich titanic Let Us Beat Swords into Plowshares. But recently these sculptures were joined by another curious object: a dark-brown wooden structure, studded with plants and topped by a pitched roof. The Eco Living Module, built to coincide with the United Nations High-Level Political Forum on Sustainable Development, aims to “spark a conversation about how truly self-sufficient a family of four housing can be,” says Anna Dyson, a project collaborator and founding director of Yale’s Center for Ecosystems in Architecture (CEA).

The 215-square-foot module got its start when UN Environment and UN-Habitat contacted the Yale School of Architecture about placing a “tiny home” of some kind at the U.N. Headquarters for the upcoming sustainability forum. That request was passed to the CEA, a research venture that straddles the university’s School of Architecture and School of Forestry & Environmental Studies, as well as New Haven, Connecticut–based Gray Organschi Architecture, a firm specializing in sustainable wood construction. The CEA and Gray Organschi Architecture are longtime collaborators and decided to tackle the challenge together. (Architect and firm cofounder Alan Organschi also teaches at the Yale School of Architecture.)

The firm designed the module’s architecture, carefully devising a wood structure that could accommodate sustainability systems (such as plant wall, photovoltaics, water harvesting system, just to name a few) that the CEA would furnish. The team met in person once, collaborating mostly through a shared digital model. “We met on Saturday morning July 8th, 6:00 AM, where the CEA drove their systems to set in with their crates,” says Alan Organschi. “We pulled our building in, and there was this moment where all these incredible systems slid into the cabin…it was amazing.”

The module’s sustainability credentials begin with it’s main architectural material, cross-laminated timber (CLT) spruce, a renewable resource that doubles as a carbon-sink. (Gray Organschi Architecture is a longtime advocate for timber as sustainable material, though the architects are quick to point out that other materials—such as brick or bamboo—are more appropriate to timber-starved regions.) Its CLT panels also feature a thick layer of wood fiber insulation which keeps the interior temperature stable. The large pitched roof, which makes space for an upper-level queen-sized bed, also encourages the stack effect, where hot air from the lower level rises and vents through the roof, and creates a cooling draft.

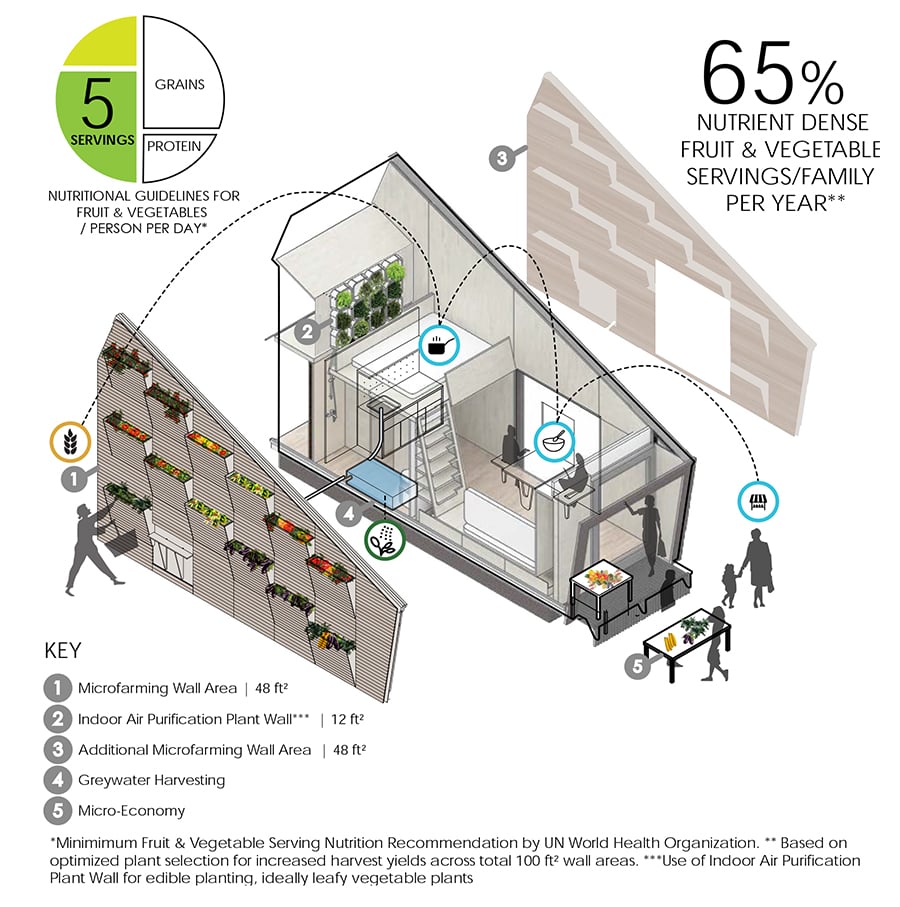

Beyond its CLT, the module isn’t short on high-tech eco-friendly systems. The power generated by a solar panel array—up to 3 kW in New York City, enough for a family of four, says the designers—is stored in batteries that subsequently power a radiant heating/cooling system and a condenser that extracts water from ambient humidity. That water, combined with captured rainwater, could supply more than five gallons of water per day—water that could go toward drinking, washing, bathing, and irrigating and internal and external plant walls. The internal plant wall (located on the module’s upper level) features hardy, air-purifying plants such as Boston fern, golden pothos, English ivy. The external plant wall features species like cilantro, parsley, spinach, collard greens, and kale. Dyson says “we can deliver six portions of fresh produce for a family of four for over 260 days out of the year,” a supply that could increase in the sunny, wet tropics.

The module’s rugged construction and self-sufficient systems add up-front expense, but its designers see that as necessary for success. They say the module needs to function in poorly-planned, rapidly urbanizing cities, or in emergency settlements created by war and natural disaster.

“For most environments that we work with, like rural to urban migration, it’s very, very hard to go into the ground with foundations,” says Dyson, who adds that housing shouldn’t “stick people who have no means to pay with an electrical bill, a water bill, insecure energy sources, and insecure water sources.” Moreover, emergency settlements and slums frequently become permanent fixtures, underscoring the need for durable, quality dwellings that can be rapidly deployed.

The U.N. is just the first stop on the module’s world tour. It will head to San Francisco in September, Quito, Ecuador in November, and Nairobi, Kenya in March. For the latter two locations, the module will be replicated with local materials to match each region’s resources and climate. The CEA and Gray Organschi Architecture are also in talks to mass-produce the module, though those discussions are in their earliest stages, and neither can estimate the module’s future cost per unit. In the meantime, both collaborators are just thankful to have their design on what amounts to the world stage.

“This is our life’s work…we’ve been doing this for decades in different ways,” says Dyson. “The materials, the water, the energy, all of the different systems. We had this incredible golden opportunity to put it all together in a way that is very unusual.”

You may also enjoy “New Talent 2018: Architect Thomas Kosbau Is Helping Create the Next Generation of Green Urban Tech.”